Breaking Down the Binary

Male? Female? How about neither, both, or something else entirely? Kate Bornstein ’69 and Dréya St. Clair ’05 talk about living beyond “M” or “F”—and about the experience of starting to find their non-binary selves on the Brown campus of both the 1960s and the 2000s.

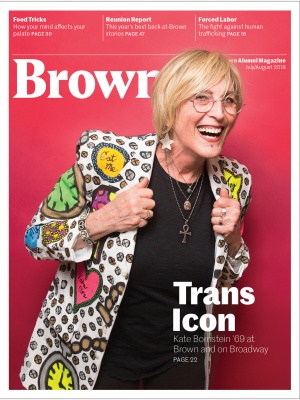

She wears the moniker reluctantly, but performer, playwright, author, and activist Kate Bornstein ’69 is a bona fide gender-nonconforming icon, at least as far back as her seminal 1994 book, Gender Outlaw, which—years before Chaz Bono, Laverne Cox, Chelsea Manning, and Caitlyn Jenner became household names—imagined gender identities that did not fall neatly into the societal binaries of male or female. More books followed, including Hello, Cruel World; A Queer and Pleasant Danger; and My Gender Workbook. This spring, Bornstein turned over a lifetime of papers to the John Hay and Pembroke Center archives (“A huge get for us!” says Pembroke archivist Mary Murphy, who adds that Bornstein turned down a request from a library at Harvard; see sidebar below), and she started preparing for her role on Broadway this summer in Straight White Men, which Young Jean Lee developed while a playwright in residence at Brown. Bornstein took time out one Sunday afternoon to open up her East Harlem apartment (where she lives with her wife—author and sexologist Barbara Carrellas—two cats, and a pug dog) to BAM.

We were joined by Dréya St. Clair ’05, an actor, artist, and development officer at the New York City think tank Demos who shares with Bornstein the experience of further discovering her gender-nonbinary identity while at Brown. That’s not all they have in common: St. Clair actually lived in the apartment above Bornstein and Carrellas her first two years out of Brown before getting her MFA at CalArts. Like many younger trans and gender-nonconforming folks, St. Clair calls Bornstein “Auntie Kate.”

For three hours, with Carrellas and the pets roaming in and out of the room, Bornstein and St. Clair discussed the challenges and joys of asserting a “not male, not female” presence in a world that is only beginning to open up to the idea of transgender visibility and rights, and of identities that don’t fit perfectly into boxes. Here are some excerpts.

Let’s talk about Brown first. What were your experiences like?

Kate Well, I entered Brown the fall of 1965. I grew up in Asbury Park, New Jersey. My father was a doctor and my brother didn’t become one, so I was expected to. I was accepted to Brown’s six-year premed program.

Dréya Oh my God, Auntie Kate, I didn’t know you were a Plee-mee! [Slang for PLME, Brown’s premed program].

Kate Well, it lasted one day. I was signing up for classes and I thought, I don’t want to spend six years studying math! No way! So I dropped it.

So what was your inner identity at the time?

Kate I knew I wasn’t comfortable being a boy, and I did not want to grow into being a man. But at the time there were no other options except for me to be a complete transsexual, and that was way too much of a freak thing. I also don’t remember there being a lot of Jews like me at Brown at the time. Our first week, my roommate said to me, “Bornstein—that’s a Jewish name, isn’t it?” And I said, “No, it’s Irish-Catholic.” And he came back around to me and said, “Admit it, you’re really Jewish, aren’t you? Where are your horns?”

At Brown in 1965? Are you serious?

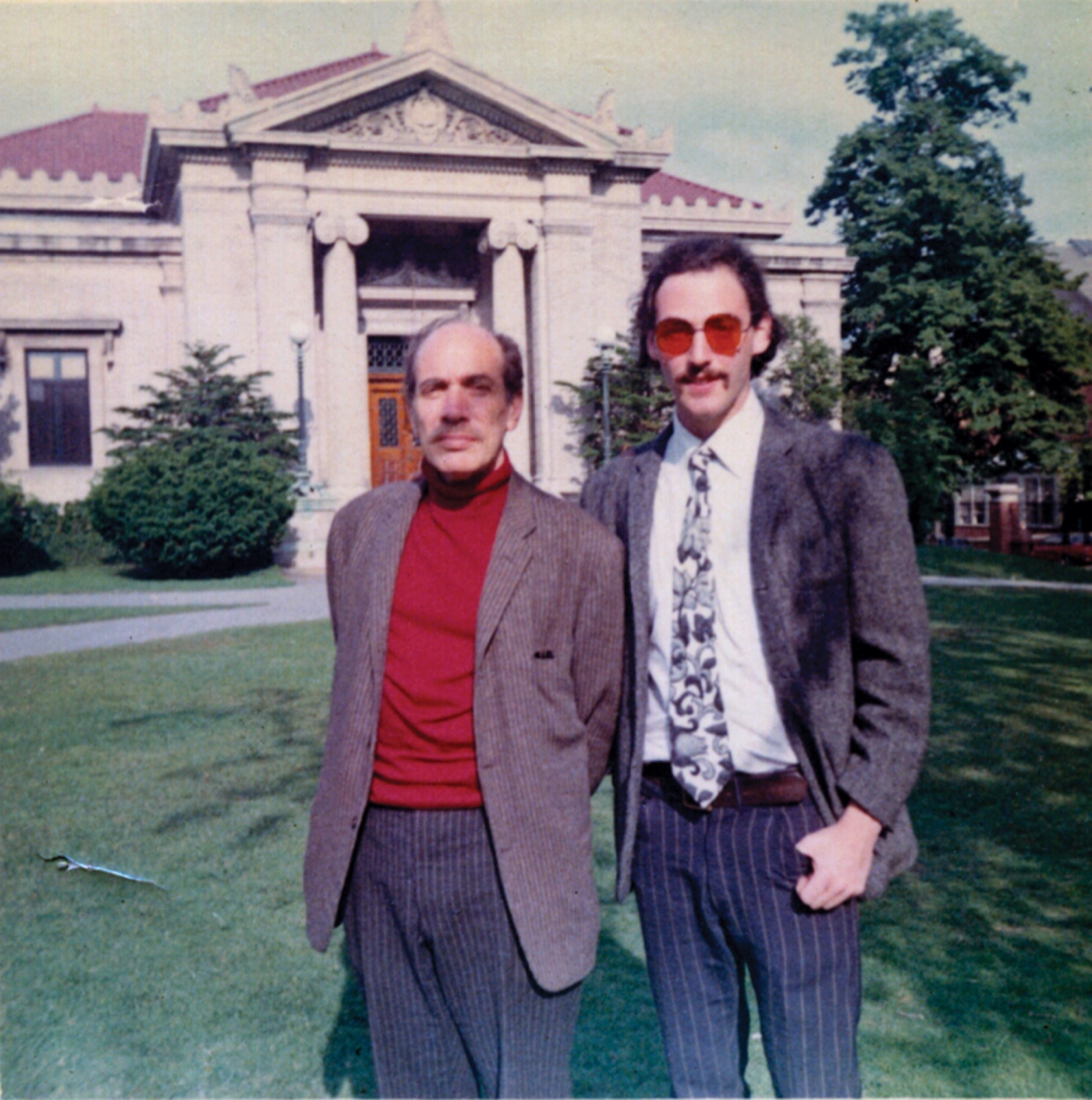

Kate Yep. Listen, at that time, Brown wasn’t so elite or progressive. It was Ivy League, yes, but it was just a big drinking school. That was the big common denominator—drinking. As for me, I found my community in theater. That’s where I felt safe, where people weren’t being exaggerated males or females. Everyone was sleeping with everyone. We knew who the gay boys were and nobody picked on them. Still, there was no gender ambiguity until 1967. That’s when the hippies happened. Suddenly I could wear purple bell bottoms, flowered shirts, and beads, and still be a guy. I suppose there was a whole lot of transgender expression going on in New York and San Francisco, but not at Brown.

So I would sneak into the wardrobe department of the theater at 2 a.m.—I had the keys because I was always working on shows—and I would pick out a princess outfit, a Shakespearean queen, ball gowns. I’d get dressed up and looking in the mirror, and it just felt so right. But there was no word for it! Transvestite was a word but always said with a sneer. I wanted to be that even less than I wanted to be transsexual. Being a transvestite meant that you only dressed as a woman when you were hiding. I guess today we would call it “fluidly gendered.”

Dréya, what about you?

Dréya I officially started Brown the fall of 2001, but I did the pre-summer program there before that as a way of not having to go home. There was a lot of domestic violence there. We moved from Jamaica to Brooklyn in 1990. My father was very verbally and physically abusive toward my mom, and I was a momma’s boy who was constantly begging my mother to leave. As for me, excelling in school was a way for me to hide my difference. I started my freshman year at Brooklyn Tech, a very competitive public school, but because I wanted to get away from my home life, I applied for the ABC [A Better Chance] program for inner-city students of color and ended up finishing high school in Edina, Minnesota, a very affluent white community.

So I went into Brown in fall 2001. That was the first time I saw people who weren’t exactly gender-nonconforming, but . . . well, a lot of gay white men in particular who seemed very free in their identity. In my freshman unit, there were a bunch of us gay and bisexual kids all wanting to come out. Many of them said they were gay, but I started by saying I was bi. Again, my friends were predominantly white, which wasn’t my background, but I still felt liberated for the first time. I’d still “de-gay” myself when I went home. I remember once when my father said he was coming to visit. I had to skip a class to find the time to “de-gay” my dorm room, take down the pictures of hot men and put away the tight clothes and the bit of makeup I was wearing. That was stressful, and I generally stayed on campus during breaks and didn’t go home.

My saving grace at Brown were my black female friends who just accepted me as one of them and gave me a sense of security. We’d talk about our hair and makeup and all that good stuff. They told me that black guys on campus were saying about me, “Who is this new hot chick?” But there was one black guy, a basketball player, whose presence terrified me. He’d always look at me in a hostile way. One day I was walking across campus and passed him and he shook his head at me disapprovingly. And I just smiled and nodded my head at him, like, “Oh, yes I am, and oh, yes I can.” And I walked away thinking, “I didn’t die. He didn’t punch me.”

That was very empowering. And so was getting involved on campus. I was involved in the Minority Peer Counseling community, and I was a programmer for Caribbean Heritage Week. But by spring of freshman year I was hugely depressed over hiding my identity and told my mother I was gay. She said, “This isn’t what I wished for you, but I love you, but let’s just not tell your father, okay?” But then that summer when I was home my whole family, all the aunties and cousins, called me downstairs and started praying over me, “Please give André the strength to cut his hair and don’t make him gay.” I just flat walked out of the room.

By the end of my time at Brown in spring 2005, I was basically the only identified “trans” student on campus, even padding my chest at one point because for a while I thought it would be cool to “pass.” [Meaning to appear as conventionally female to most eyes.] I actually had started meeting trans women of color not on campus but in the broader Providence community, in clubs, and some of them were pressuring me into taking hormones, telling me that I had soft features and that I could easily transition and pass on the streets. But I didn’t want that. I was saying, “I’m a boy who’s feminine and dresses like a girl and there’s nothing wrong with that.” And I’ve stayed on that course ever since.

Let’s talk about this idea of passing a bit. Many cisgender [non-trans] and even trans folks think that to be trans, you have to fully “pass” or pull off looking like the gender opposite the one you were assigned at birth. To ask you both a devil’s advocate question, why wouldn’t you want to “pass?”

Dréya What about all the trans folks out there who can’t pass, no matter how hard they try? Passing should not be the end-all and be-all of being transgender. I admit, now I sometimes ask myself how much easier my life would have been if I had just fully transitioned with hormones and surgery. Even with [black trans actor and activist] Laverne Cox being on the cover of Time a few years ago with the headline of “The Transgender Tipping Point,” people still don’t understand what being trans is if you’re not perfectly passing.

Kate Dréya, everything you’re saying is what a few of us started realizing in the late eighties. What had kept me convinced that I was not transsexual was that I’d have to be a woman. But I loved women—they were everything to me romantically and sexually. No one in those days was separating between sexual orientation and gender identity. I learned that difference in 1983 and then finally began my gender transition in 1984. I realized that I could be a woman and a lesbian! And you’re right about gender as a social construct, Dréya. “Deconstruction” was the word we were all gnawing on in the early nineties. When I published Gender Outlaw in 1994, I was trying to describe myself, to say, “I’m not a man and not a woman.” That was such a relief! Such a sense of [she exhales happily].

Dréya Gender Outlaw was the first book I read that made any sense to me in terms of what I was feeling. You wrote in it, “Be okay with being a freak.” And I was like, “Yes!” I knew society was looking at me that way and that I was looking at other gender-nonconforming people that way. But I wasn’t offended by it. It was just about being in your body as you are.

Kate And where did that let you go?

Dréya I felt like I could feel as feminine in my own body as I wanted to feel, wear heels and a dress, without having to pad my chest or take hormones. It totally liberated me.

Kate What’s so funny is that, when I wrote it, it was theory, but today people like you have made it practice. When I look at you, Dréya, I feel a great joy.

Dréya Thank you. I’m glad it touches you that way because you deserve it. Each generation makes it so much easier for the next. I went back to Brown recently to be on a panel and there was so much gender fluidity and gender-nonconformity on campus. And someone said to me, “Look around! When you were here, you were the only one!” But Auntie Kate, I want to ask you: How do you feel about being seen as an icon within the trans movement?

Kate Well, I prefer “Auntie” over “icon” or “mother.” “Icon” implies, “This is how you do it,” and “mother” implies “You gave birth to this,” while “auntie” is more like, “I’m here to help you any way I can, honey, and would you like a cookie?” Or that I’m the fun one, like Auntie Mame.

Dréya Laverne Cox says she likes to be a “possibility model” instead of a “role model.” I like that there are multiple possibilities for what we can be. But I think that mainstream people think that to be trans means you have to be a full transsexual.

When it comes to the mainstream, what are the pros and cons for both of you of playing the educator role?

Kate What tires me is having to teach the same thing over and over because I haven’t found a new way to explain a broader concept. So I’m always trying to go deeper. Such as, recently, I’ve started saying that, really, gender is a source of suffering for all of us. Think about it. There’s misogyny and sexism. And also the pressure on men to be men. And then, if you ever get to where you want to be, gender-wise, age is going to make you lose it eventually. So we’re all grabbing at a chimera when it comes to gender. Where does advertising make most of its money? Convincing us that we’re not quite as much of our gender as we should be! We’ve been looking at gender in two dimensions all this time: male and female. But today we can add the dimension of imagination. And there’s even a fourth dimension: Time. Because our relationship to our gender can change throughout our lives. I mean, when I came to Brown I was six feet tall, which was my height up until my chemo for lung cancer a few years ago, and now I’m 5’8”. I have shrunk four inches! I just turned 70. I’m a little old lady! And it’s delightful to be able to walk through the world and say, “Hello young man, hello young lady, how are you, dear?”

Dréya I’m gonna be honest. Always having to be the educator can be very heavy. I’m very often the only trans person in the room and sometimes, like today, the only black person in the room, too. I have to answer the same questions a million times. I’m always weighing the room to see what people can and can’t understand and absorb. It’s labor. It’s hard and it’s taxing. Some people feel like they’re entitled to my story for free even though it costs me time and emotional energy. I especially felt like this after the presidential election. Suddenly everyone wanted me to explain to them what it’s like to be black and trans. I had to pull back from public appearances, even though I’ve recently picked up again.

Kate I’m working on a new book called Trans: Just for the Fun of It. Because the fun of being trans has gotten lost. The only person holding up the fun banner anymore is RuPaul and he gets shot left, right, and center for it. [RuPaul recently caused a controversy by saying that he would likely never let cisgender women compete on his hit show, RuPaul’s Drag Race.] You can’t talk about these issues anymore without walking on eggshells. Whereas before we used to be able to use the word “tranny.”

Ah, yes, the T-bomb! Dréya, how do feel about that word?

Dréya “Tranny” doesn’t offend me the way the N-word does. I don’t even like that word when it’s used by a black person. And I can’t exactly explain why. I think “tranny” depends on how it’s used. So many times, trans girlfriends have said to me, “Tranny, please!” [laughs]

Kate It’s a family word among trans people. But I learned my lesson about how the word can be a trigger when I was on the show I Am Cait [reality show about Caitlyn Jenner’s coming-out as trans] when [trans author and activist] Jenny Boylan told me a horrible story of being physically abused for almost an hour with someone screaming “tranny” at her. So I don’t use the word lightly. I use it when I’m with people I consider family because I know it might trigger a serious PTSD reaction in some. But so many people today, I want to say: You’re not feeling triggered. You’re just feeling uncomfortable. And I’ve spent 68 years feeling uncomfortable, unwanted, and excluded. It makes you a stronger person.

Would you agree, Dréya?

Dréya Yeah, it makes me tough as nails. Being 34 years old in this current political climate with a president throwing daggers at trans people in the military? I live in discomfort. I’ve had to tell my cis girlfriends, when we go into a ladies’ room together, “Please, for the love of God, don’t speak to me in there.” Because it’s triggering for some women to hear what they think is a man’s voice in the bathroom and they might get reactive. I’ve had to make my girlfriends understand that that can make me very vulnerable.

Actually, can we go back and talk about Caitlyn Jenner for a minute and whether you two think she’s good for the trans movement?

Dréya I think she has a disconnect from the struggles of most people in the trans community, particularly trans women of color. On I Am Cait, you, Kate, had to play the role of educating a trans woman who just doesn’t have a clue. How did you connect to her and the show?

Kate The producer found me after the trans actor Jen Richards suggested me. On the show, we had a sleepover party at [trans actor] Candis Cayne’s place and I had a burning question for Caitlyn: “How are you dealing with the freak factor?” She was like, “What?” I said, “You know, being such a freak?” And she said, “Well, the reason I’m doing this show is so trans people don’t have to be freaks.” My job on the show was to push her out of her right-wing comfort zone and we actually still have a lovely relationship. She certainly hasn’t struggled the same way most trans people, particularly those of color, have.

She’s had a lot of privilege. That’s something people are talking about a lot these days—race privilege, class privilege, gender privilege. What about the two of you?

Dréya I’ve experienced employment discrimination as a black trans woman. And I’ve got a lot of student loan debt from both Brown and CalArts. I’m from a working class family and because I’m the eldest, I give financially to them. Since Brown, I’ve learned to survive alongside people who have a lot more privilege than I do. And there’s an empathy gap. People don’t understand the pain of being black—and exponentially more if you’re black and trans. And I often don’t see myself reflected in white trans spaces. My education is a double-edged sword. It makes people perceive me as middle-class. And trust me, I love dressing well and I can project and live that just fine. But I’m about to be 35 and people are inviting me to their destination weddings, baby showers, expensive dinners. They don’t understand being the first generation in your family to go to college.

What about you, Kate?

Kate Well, I have “passing” privilege, white privilege, and the dubious privilege of being old. But the biggest privilege is my voice. I have a very loud voice in the trans world—perhaps the loudest. I turn down gigs and urge people to give someone else a chance. But I still don’t have money. I’m living hand-to-mouth. [to Dréya] The privilege you have of being able to come out at 20 and find work would’ve been inconceivable to me when I was 20. So, for Caitlyn Jenner, imagine hiding who you are for over 60 years. Imagine that intense kind of suffering. Back in the day, we all learned that you give your trans family the benefit of the doubt. And Caitlyn’s not getting that. She’s not out there attacking or doing harm to any trans people. She started a foundation to help homeless LGBTQ youth.

To wrap up: Dréya, where would you like to be in 10 years?

Dréya I would love to get back more into acting and producing more of my visual artwork. I’d love to play a badass transgender superhero! Or maybe a villain. They’re more fun. And I would love to be in a space where I could open homes for homeless trans youth. I know that, if it wasn’t for Brown, that could’ve been me. After I graduated, Auntie Kate helped me get the apartment upstairs for two years.

Kate, final thoughts?

Kate It’s really humbling that Brown is collecting my papers. Two women from the Pembroke Center came by recently and emptied out my office. And I hope there’s enough in there among the papers and the pictures and the hard drives to help future generations understand that everyone’s an onion just waiting to be peeled.