The word no didn’t exist in Galen Henderson ’93 MD’s vocabulary—not for patients, not for friends and colleagues, not even for Brown itself.

“I’ve never met someone who was such an avid listener,” says Massachusetts neurologist Carolyn Bernstein. “Whenever I would sit and talk with Galen, I felt like whatever I was discussing was the most important thing in the world to him in that moment. No matter what it was or who you were, he gave all of his attention and focus to you. Galen had time for everybody, and everybody was important to him.”

Henderson, who passed away on Dec. 26 after an illness, was an unstinting and magnanimous member of the Brown community, sharing his time, knowledge, and energy on service to various committees, large and small; on mentoring and advising students; even, when asked, narrating a video in his unmistakable, mellifluous speaking voice.

In a letter to the Brown Corporation announcing his death, President Christina H. Paxson praised “Galen’s warm smile, thoughtful and insightful assessment of complex issues, and his steadfast commitment to the well-being of his patients, his colleagues, Warren Alpert Medical School students, and everyone he met.”

A native of Tunica, Miss.—population 987—Henderson attended a summer program for talented African American high school students at Tougaloo College in 1984. There, he became enamored by the HBCU’s storied legacy of civil rights activism and its success educating Black MDs and PhDs. “I wanted to be part of that history,” he recalled in a Brown Medicine article. He came to Brown through the Early Identification Program, which selects two promising sophomores each year for enrollment at Brown after graduating Tougaloo.

Brown would become one of his great loves; the other was his wife, Vanessa Britto ’96 ScM. The pair met while attending a conference on College Hill in 1989 and started dating a couple of years later, Britto recounted for a 2018 story commemorating their establishment of a scholarship for medical students. When they became engaged, Britto had an idea: “Because we wanted the same people at our wedding and at Galen’s medical school graduation, we thought, ‘Why not do this crazy mashup?’ So we were married on Sunday and graduation was on Monday.” (Their 25th wedding anniversary party requested donations to their scholarship fund in lieu of gifts.)

Henderson began his postgraduate education with an internship at Rhode Island Hospital, where he was the only African American in the program. “Although he had a formal demeanor, he was kind and generous, helping his peers without fanfare and demonstrating compassion to his patients,” recalls Dominick Tammaro, program director for 30 years. “He balanced confidence with humility and consideration of others.”

Henderson was so good that members of the faculty tried to persuade him to stay in primary care. “Even as a third-year medical student starting his clerkship, it was clear that Galen was a superstar,” remembers Senior Associate Dean for Academic Affairs Michele G. Cyr, director of the clerkship in the early ’90s. “I shamelessly tried to convince him to go into internal medicine, but his passion for neurology won out.”

After his internship, Galen entered the Harvard Longwood Neurological Training Program, only the fifth African American physician in its 40-year history. He went on to complete a fellowship in stroke and neurocritical care at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and became the country’s first African American neurointensivist and the first African American fellow to be inducted into the Neurocritical Care Society. Once his training was complete, he joined the staff of Brigham and Women’s—eventually becoming director of its neurological intensive care unit—and the faculty of Harvard Medical School. During his tenure, the neurocritical unit grew from five to 20 beds and is now one of the busiest ICUs at the Brigham.

In this role, Henderson dealt with life-and-death decisions every day; he was a national expert on brain death. He received awards from three different U.S. secretaries of Health and Human Services for his contributions to the development of the Organ Donation National Collaborative.

Even at the peak of his career, he made time to mentor medical students, among them neuro-oncologist Nicolas Gonzalez Castro. “Galen was manning the neurology table at one of the residency programs’ showcases,” Castro recalled for the Brigham Bulletin. “I was impressed that someone so senior and busy—he was already an assistant professor and director of the Neuro ICU—would spend a whole evening chatting with medical students. I was struck by his approachable and caring demeanor, while also coming across as ceremonial and dignified. This helped him develop enduring relationships with trainees and colleagues, as well as helped him guide patients and families through very difficult decisions.”

Britto, who is associate vice president for campus life and student services and executive director of health and wellness at Brown, says that since his passing, “So many people have reached out to me,” from fellow physicians to the custodian on his hospital floor. “The throughline in their comments is his warmth and love of people. He wanted to find that human connection —in other professionals, students, patients. He believed we’re better for having known each other.”

Dedicated to elevating opportunities for those who are underrepresented in science and medicine—or what he called “preparing his shoulders for the next generation of people who don’t fit the stereotype of what a physician looks like”—Henderson was named chief diversity and inclusion officer at the Brigham, helping to usher in the most diverse classes of residents in hospital history. In 2021, he was the inaugural recipient of the Warren Alpert Medical School’s Senior Alumni Award for Excellence in Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion for his work to increase the number of women and physicians from underrepresented backgrounds in academic medicine; Brown announced that the award will bear his name going forward.

Henderson was the first medical program graduate to be appointed to Brown’s Corporation, serving two terms as a trustee, and the first to be president of the Brown Alumni Association. He served as president of the Brown Medical Alumni Association, was a member of the Brown Medicine and Brown Alumni Magazine editorial boards, and served on University advisory councils for medicine and for relations with Tougaloo. In 2014, he received the Brown Bear Award, the University’s highest honor.

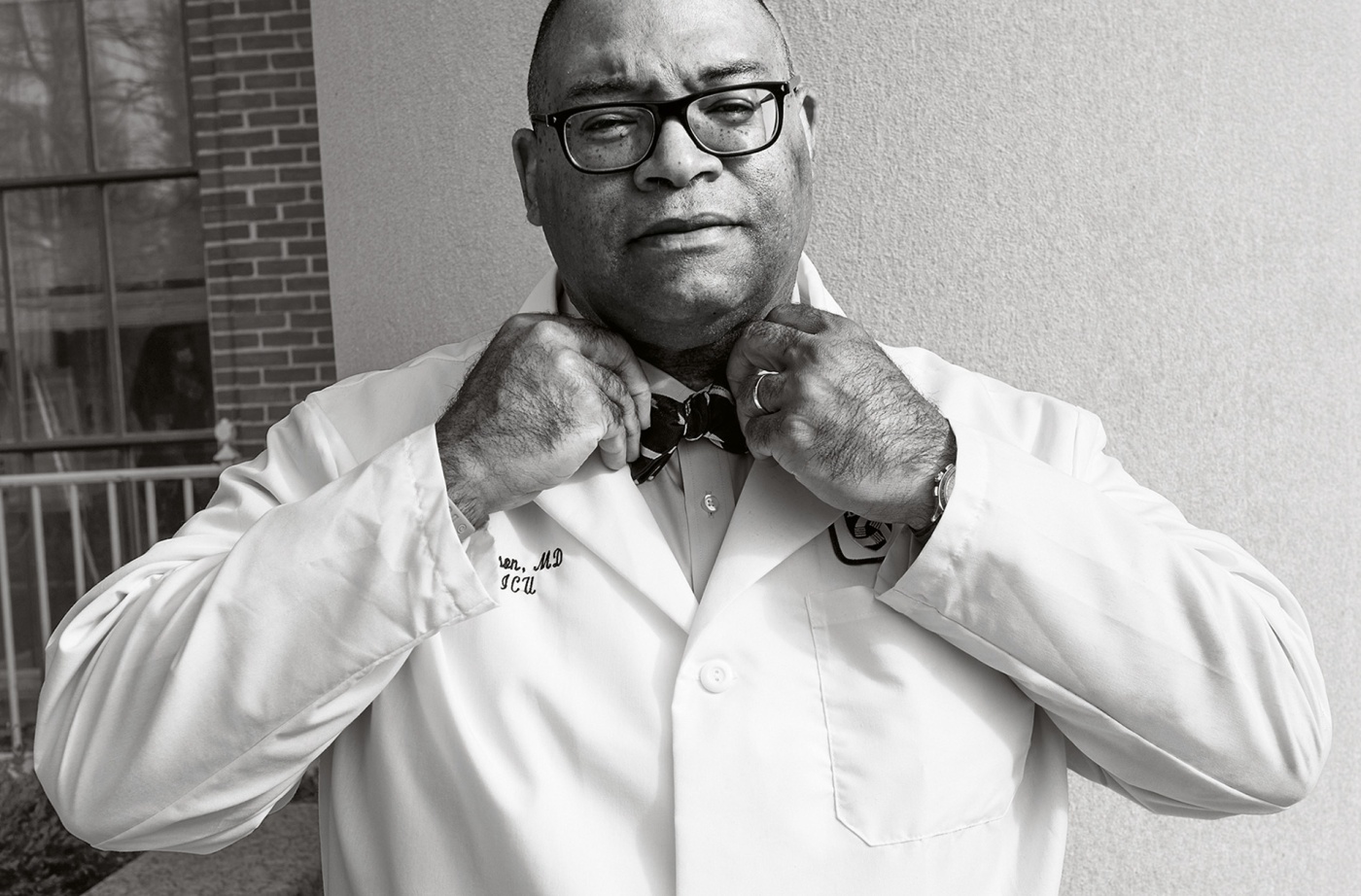

Jeffrey Hines ’83, ’86 MD, his friend and fellow Corporation trustee, reflected on the man beneath the white coat and signature bow tie during a January celebration of life, including his annual pilgrimage to the Newport Jazz Festival. “Galen loved jazz; in particular, Galen loved John Coltrane. We all know that Galen loved to give advice; I’m certain he’s giving Coltrane advice right now,” Hines said. He was also a self-described Francophile who studied conversational French for many years. He and Britto were committed to medical mission work, primarily in her ancestral home of Cabo Verde, and they enjoyed traveling internationally.

Rather than mourn him, Hines says, “Galen would want us to feverishly love those closest to us…Aspire to be authentic, enjoy jazz, ride a bike, and learn a little French…do what is not easy, what is uncomfortable, and inconvenient. Do what is good.”

In addition to Britto, Henderson is survived by his mother, Peggie A. (Bonds) Henderson of Tunica, Miss., and his sister, Erika Winfrey (Harold) of Memphis, Tenn.