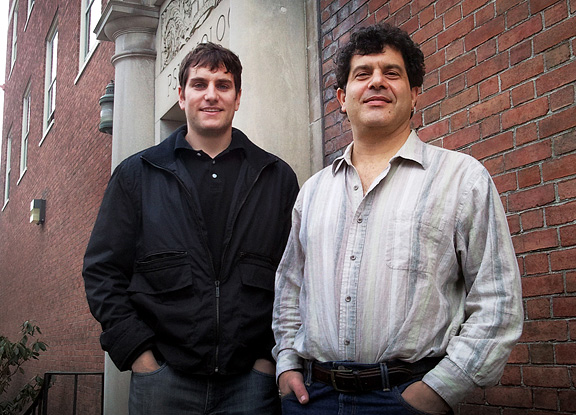

Quick, describe how a bicycle works. Not just “you pedal it and it goes,” but put each piece of the process together in your mind, step by step. You probably know there are two wheels, two pedals, and a chain, but, if you’re a casual rider, explaining just how the gears, derailleur, and other parts work with them is probably just beyond your grasp. Still, Brown professor of cognitive, linguistic, and psychological science Steven Sloman and his coauthor, Philip Fernbach, are willing to bet you thought you knew how a bike works.

The reason we’re not constantly bumbling through life, despite our limitations, is one another: we’re part of a community of knowledge that, collectively, knows a lot. We’ve evolved to develop a narrow area of expertise and to rely on others for theirs, so that together we can accomplish more than any one of us can on our own. The Internet has only amplified this phenomenon. So much of what we think we know is, in fact, information that lives online or in books or in the heads of our friends and family; we confuse what we know with what we can easily find out.

The Knowledge Illusion is most captivating when it arrives at some of the real-world implications of why our brains operate the way they do. Numerous studies, for example, have shown that “the success of a group is not predominantly a function of the intelligence of its individual members. It’s determined by how well they work together.” The authors’ observations about the echo-chamber that develops when we rely too heavily on our own community for information—a tendency that dates to the very origin of our species but which can have a real downside during, say, a polarized election season—feel apropos in 2017.

The Knowledge Illusion reads like a book written by two cognitive scientists eager for a popular audience. It’s full of breezy descriptions of studies and theories, with many anecdotes to illustrate their points. As if in homage to their central thesis, they at times over-explain, layering on the anecdotes to make sure the reader gets the point.

Even as it lays bare how self-deluded we are, The Knowledge Illusion is, in the end, not meant to discourage us from our illusions. Without thinking we’re capable of more than we are, we’d never set lofty goals, nor accomplish them. Yet at the same time the book is an important reminder of how much we rely on one another, and how valuing one another’s contributions is essential if we’re to survive and thrive.