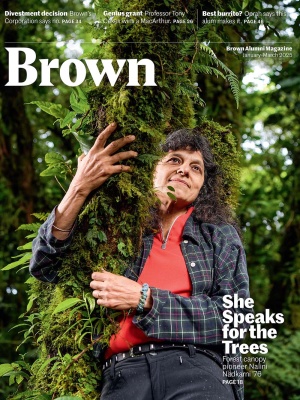

Treetop Trailblazer

From programs in prisons to her own version of Barbie, pioneering ecologist Nalini Nadkarni ’76, “Queen of the Forest Canopy,” looks for ways to get us to connect with the arboreal world—and with one another.

Nalini Nadkarni plunged 50 feet from her tree on July 3, 2015.

It wasn’t her tree, exactly, but one of the many bigleaf maples that she’s been studying for 40 years on the Olympic Peninsula. Here a warm ocean current propels moist Pacific air against coastal mountains, dropping some 90 inches of rain a year. In this unique temperate rainforest, these maples soar above the Quinault River basin alongside Sitka spruce, Douglas fir, alder, and Western redcedar.

These giants—especially the bigleaf maples—gather a thriving drape of living mosses, liverworts, and lichens. Nadkarni had pioneered research into these aerial gardens decades earlier as the first chapter of a distinguished career.

On this catastrophic day, Nadkarni was with three graduate students—two new recruits from Evergreen State College, where she’d taught for years, and Jordan Herman, a new graduate student at the University of Utah. Herman had jumped at the opportunity. “What could be cooler than traveling up to the Olympics and climbing trees and doing science with the Nalini Nadkarni?”

They gathered in the forest below the towering trees. After an equipment check and training review, Nadkarni paired with a nervous, novice climber. She went up first—just another of perhaps 5,000 such climbs over her life. Herman went first up another tree.

Then Nadkarni’s partner began to ascend. Up on her branch, Nadkarni leaned over and was surprised that she didn’t feel the usual tension. Later she learned that her rope, only eight months old, had simply broken. She began to fall.

Herman heard a snap, a silence, then an impact. “It sounded exactly like a fall,” she says. Nadkarni didn’t scream or yell, plummeting silently, like a sack of sand. Then Herman heard a plaintive “Nalini, are you okay?” That helpless question came from Nadkarni’s partner, the new climber, now stuck six feet off the ground.

Everything shifted into high gear. “I quickly zipped back down the tree and ran over,” recalls Herman. Nobody had meaningful wilderness medical training, and the group wasn’t sure what to do. There was no cell service. A friend who had arrived just after the climbing began tore back to his car and drove maniacally to the ranger station. The Evergreen students also decamped to the road in case someone drove by.

Nadkarni was unconscious for about 10 minutes. Herman felt helpless by her side.

Then Nadkarni started to rouse.

A serious accident takes the victim out of themselves. This was not, currently, Nalini Nadkarni, University of Utah biology professor and National Geographic Explorer. She had gone inside somewhere to protect herself. Herman was interacting with a person who had just suffered a brain injury—among a litany of other unknown damage—from falling 50 feet. “I was holding her head in place so that she hopefully wouldn’t incur more damage.” But Nadkarni, in serious pain, refused to stay still. She believed something was piercing her back and hips and wanted to get off of it.

The forest floor was soft and flat.

Falling from 50 feet isn’t always fatal, but Herman knew time was short. “I couldn’t have guessed the extent of her injuries,” she says. “I felt so focused on her in those moments, just trying to be there for her. And I wasn’t really thinking about her dying at that point.”

Nadkarni needed serious medical attention and it took nearly six hours for help to arrive. Two chopper flights and several procedures later, she woke up in the ICU at Harborview Medical Center in Seattle. She had nine broken ribs, a broken fibula, and her pelvis was broken in three places. She lost her spleen and cracked her C2 vertebra. Five thoracic vertebrae simply exploded from the impact.

“I was really close to death,” says Nadkarni. She had four operations in just the first few days and spent two months in the hospital.

Nadkarni had come to the Olympics to continue her long-running research on how disturbance affected moss and microbial communities in the canopy. Now the disruption was personal, existential. What lay ahead for this wildly charismatic powerhouse? With these injuries, at 60 years of age, nobody expected her to walk, never mind climb trees again.

Amid the pain, the prodding, and the ICU hallucinations she wondered: “Who am I going to be? What am I going to be able to do?”

Sweet refuge

Tree climbing began early. Nadkarni grew up in Bethesda, Maryland, the middle child of five in a somewhat chaotic household with a Hindu father and a Jewish mother. Just outside the rambling old house, eight sugar maple trees flanked a gravel driveway. There were always chores and tests and homework, but the trees beckoned.

“It was my place,” says Nadkarni. None of her siblings climbed, so the trees were also a refuge. She hand-lettered a kid’s guide to tree climbing titled Be Among the Birds: A Child’s Guide to Tree-Climbing. In the technical guide to switching trunks and getting higher, she also promised to do something for the trees.

She arrived at Brown in 1972 amid the blooming of a new curriculum. The flexibility allowed her to spend an entire year at the University of British Columbia taking forestry courses not available at Brown. She also explored her love of dance. Upon graduating, she tried to secure a postgraduate traveling grant to split between the conservatories of Paris and a biological research station.

She spent five months in a modern dance troupe in Paris but 16 months at the Wau Ecology Institute, a tiny field station in Papua New Guinea. There she helped the director study leaf-eating beetles and learned how field biologists come to understand such diverse systems.

Graduate school included a semester in Costa Rica with the Organization for Tropical Studies (OTS). Her very first morning in the cloud forest of Monteverde featured a short walk along the Sendero Bosque Nuboso (Cloud Forest Trail). Nadkarni’s eyes were riveted to the treetops. “What’s going on up there?” she asked her professors. “What’s the biodiversity? What’s the contribution of these plants? What’s the connection?” They couldn’t answer because, like much

of the rest of the forest, it was an unknown world. “At that time it was called ‘the last biotic frontier,’” recalls Nadkarni. It seemed like an intellectual smorgasbord that she would never, ever be able to finish eating.

This was 1979, and there were a few canopy pioneers at work. Ecologists at Oregon State were driving pitons into tree trunks to reach treetop lichen. Don Perry at Cal State University in Northridge was studying canopy pollination. He used a crossbow to deliver ropes over high branches, then climbed the rope into the canopy. By sheer luck, Nadkarni’s OTS course visited La Selva Biological Station while Don Perry was there. He gave a short talk about his research and Nadkarni wanted to know how he reached his platform, 125 feet above the ground. They arranged a trade: she took photos needed for a Smithsonian magazine article and he taught her how to climb.

Rope climbing is made vastly easier with a tool called the jumar ascender. You need two ascenders—one for your seat harness and the other for your leg loops. When you’re sitting in the harness, you move the leg ascender up. Then you stand up, and slide the harness ascender up. Back and forth, up and up. And up—some trees don’t even have a branch below 100 feet.

On her first climb in Perry’s rig, Nadkarni stopped about 15 feet up, seized by joy. “I just started screaming at the top of my lungs,” she says. “I realized, at that moment—that first climb—that I was at the portal of this virtually unknown world.”

Her graduate committee at the University of Washington was less enthusiastic. “There’re so many questions on the forest floor,” said one professor. “Why do you have to go to the canopy?” She found new advisors and secured independent funding from UNESCO’s Man and the Biosphere Programme.

In 1980, $50,000 was a huge amount of money. It allowed her to go back and forth between Costa Rica and the Olympics and paid for climbing gear and lab work.

Magic carpet

Climbing in an intact rainforest is quiet, damp, and deeply shaded. There’s no wind below. The light brightens as you ascend, the soundtrack resolving into clearer notes—of insects, birds, monkeys. Leaves rush and rattle in the wind.

A hummingbird may dart by. Finally you fling your leg over your branch up among the canopy plants. You need a little time to get adjusted. “It’s like you’re in an oak prairie,” she says. “There’s nothing above you except these few branches that are the highest branches of these emergent trees.”

You’re sitting on a magic carpet of plants like orchids and bromeliads, nestled within a flat layer of mosses and liverworts and lichens. The accompanying soil smells like rich garden humus and sustains everything from ants and microbes to trees and shrubs.

At first the bulk of Nadkarni’s science was like 19th century Victorian exploration: a lot of descriptions, a lot of drawings, a lot of lists. The canopy-dwelling plants are called epiphytes, and because they represent just a small part of the biomass of the forest it was possible they didn’t have a significant role.

Climb by climb, Nadkarni sketched out the canopy. “It’s like a forest within a forest,” she says. “You never get tired of this kind of layering, this web of interconnections.”

Her inaugural discovery was that roots in the forest canopy emerged high among the host trees, tapping that canopy soil. “Epiphytes are a small part of the ecosystem in terms of their biomass,” she says. “But it’s not like they’re disconnected up there. They’re part of the dance of the forest as a whole.”

Douglas Gill, now an emeritus professor of biology at the University of Maryland, was one of her instructors on that first OTS course and helped Nadkarni design this first epiphyte research. He was quite certain it would fail. “The world changed from that moment on,” he recalls. “That’s just the first of a dozen astounding, clever, creative pursuits... She is just one of the most amazing people imaginable.”

Nadkarni decoded dazzling treetop complexity. The ever-shifting mosaic of canopy life was driven by subtle factors: changes in microclimate, propagule landing spots, even which mycorrhizal fungus is also present. “That very lack of order makes it challenging to understand and predict what’s going on,” says Nadkarni.

Conservation questions were particularly pressing. What are the effects of disturbances like forest fragmentation, climate change, or invasive species? After tundra, says Nadkarni, the montane cloud forest in places like Monteverde may be most threatened by climate change. These mountaintop systems have evolved in the presence of lots of mist and fog—when warm, moist air flows off the ocean and hits the mountains, the water vapor condenses as temperatures drop.

The higher you go up the mountain, the more and more mist and fog there is. But climate change is throttling this phenomenon. To test the impact of this change on canopy plants, Nadkarni cut meter-long mats of canopy vegetation and transplanted them to sites down the mountain with less mist and fog.

She marked the leaves with little dots of fingernail polish. More leaves died—and more plants too—among those mats transplanted to mid and lower elevation sites. Nadkarni concluded that the loss of mist and fog would have a negative effect on these canopy-dwelling plants. It was the first experimental evidence of how drying conditions might affect cloud forests.

Cultivating care

As Nadkarni’s generation of scientists continued to document damage to the planet, a more activist and publicly engaged style of science emerged. Among them, Nadkarni was ambassador for the trees. She loves trees, but not in dour,

Loraxian fashion. She loves her intimate connection with these big, beautiful living things—what she calls the greatest organisms on Earth.

She started doing public engagement with National Geographic, cooperating with documentary film projects and writing magazine articles. She proposed a Treetop Barbie to Mattel (see “Explorer Barbie,” Apr.–May ’20). She worked with dancers and visual artists.

“How could I communicate the importance of trees to people who might not share my ecological values?” she asked. “How do you get religious people to care about trees? How do you get little girls to appreciate trees? How do you get prisoners to appreciate trees? How do you get prison wardens to let their inmates appreciate trees?”

And so she built research projects and outreach programs, connecting to spiritual leaders and creative types.

Her prison work combined principle with practical. Forests in the Pacific Northwest were suffering from the harvest of wild mosses. These slow-growing forest dwellers were collected for the florist industry but took decades to grow back.

She approached the superintendent at a small minimum security men’s prison about a moss growing project. First there was training, then experiments to see which species grew fastest. “The men loved it,” says Nadkarni.

Then she recruited other scientists and conservationists to share their research in a prison lecture series. Similar projects grew in other prisons, cultivating different species of interest.

Another project looked at the power of nature imagery for inmates in solitary. The study found that after a year of showing nature videos in the exercise rooms of supermax cell blocks for one hour a day, violent infractions went down 26 percent. “It is one thing that we academics can do in the face of this incredibly unjust, horrible system of mass incarceration,” she says.

Critical relationships

The week before she fell, Nadkarni had wrapped up a year-long colloquium on disturbance and recovery—starting with trees but branching out to the interpersonal and the global—with nine other University of Utah faculty members.

The project began with a rejection. Nadkarni proposed a study of relict trees in pastures—those left behind for shade and forage when rainforest is cleared. These relicts may play an important role in recovery from deforestation and forest fragmentation. In primary forest with an intact canopy, pollination and propagation can work over short distances from tree to tree. What happens when most of those trees get cut down for pasture? Will the birds and bats that pollinate the tree cross the ocean of grass?

A reviewer challenged her to think outside her field so that any results would have broader applications. What might other disciplines have to offer in terms of parallel intellectual constructs? And so Nadkarni engaged a traffic engineer, a burn trauma specialist, a neuroscientist, a dancer, and others. Russell Isabella, now retired as a professor of human development and family studies, was one recruit. He’d never met her but called the colloquium discourse “the most unique experience” he’d had in more than 30 years in academia. “One of her specialties is seeing ways in which disparate entities can be brought together,” he says. “She’s a catalyst for new and different ways of approaching things.”

Ellen Bromberg, a modern dance scholar, also called the colloquium one of the “high points” of her teaching career. Dancing, for her, is a way of being alive in the world. “And Nalini is very alive on so many burners,” she adds.

One thing the group agreed upon: enhancing and sustaining your web of relationships was key to surviving disturbance. Refugees need to sustain their relationships with each other and with other refugee groups. Neurons must communicate with each other in order to forge neuroplasticity. Relict trees must sustain a relationship with pollinators. We presume that a successful recovery from disturbance will return us to the original state. But often we don’t recover, but come to what the group started calling a third state. “That’s neither better nor worse than the original, but it’s different,” says Nadkarni.

These lessons would inform her difficult recovery. “That disturbance had a profound and I think generative effect on me and my choices of what I do, how I spend my time, and how I feel about myself at this time of my life,” she says. “I hate to say but I’m kind of grateful that that happened. Because I feel myself now to be a more whole person who’s more content with herself in an odd way. It’s hard to describe.”

Third state

Nalini Nadkarni was convinced that she would be one of those people that got right back on the horse. “I’m so strong,” she told herself. “And my spirit is such a brave spirit.”

But she faltered. “It was fraught, fraught, fraught,” she says now. She even gave herself permission to not climb.

Then, one day in Monteverde, it felt like time to try.

Her colleagues offered to climb with her, but Nadkarni chose to go solo. Very slowly she started inching up the rope, thinking a little too much about the gear. She’s never been afraid of heights, but for the very first time she felt that fear. Finally she got to the first branch. “And once I was on that branch, once I was sitting on something solid and not just hanging out there in this three dimensional space, I felt comfortable again,” she says. “I felt okay. But it was not with the same joyful abandon that it had been before.”

The research she’s part of now is looking, more deeply now, at projecting the effects of climate change on canopy plant communities in the tropical cloud forests. She knows the dry seasons are longer now and that she doesn’t see rainbows in January the way she used to. To simulate this drier future they have stripped the epiphyte layer from 20 trees. Data loggers are installed in the tree crowns, constantly measuring the microclimate. A network of tubing measures water flowing from the tree. Like many environmental scientists she wishes now she had spent more time documenting the moisture content of soils in the canopy, or just taking lots of pictures. “What I sense every time I climb into the canopy now is that things are just not looking as healthy.”

In another 50 years, if climate change continues its pace, these epiphytes are not going to survive. And if they can’t survive, what happens to their host trees? With this experiment they’re not going to wait 50 years to see what happens. They’re speeding up the clock. “We don’t know really what the answer is going to be,” she says. “But it might have a big effect.”

“I think there’s a universality about disturbance and recovery,” she adds. When she talks about her fall, and then recovering, she’s seen how people tend to draw connections to events in their lives. Some people suppress those thoughts or think the disturbance is their fault. They don’t want to face the discomfort of thinking about it, just as people veer away from facing things like the climate crisis.

The trick is to remember that we’re not alone. “If I think about it with other people, that actually moves me more towards recovery and my third state,” she says. “And the earth is exactly the same way.”

Erik Ness is a science and environmental writer based in Wisconsin. For more of his environmental writing, check out lemonadist.com.