Think Again

The Art of Tony Cokes: We already know—saw the clips. Who said what, what went down. Necessarily quick studies, we get it, we got it, we’re good. But what if we don’t?

Tony Cokes’s video art works have, for over three decades, disarmed us just so: introducing uncertainty to our certainties. Slyly forcing us to question things we thought we knew. Managing—of all things—to change our minds, rocking our worlds (and bodies, through sound) in the process.

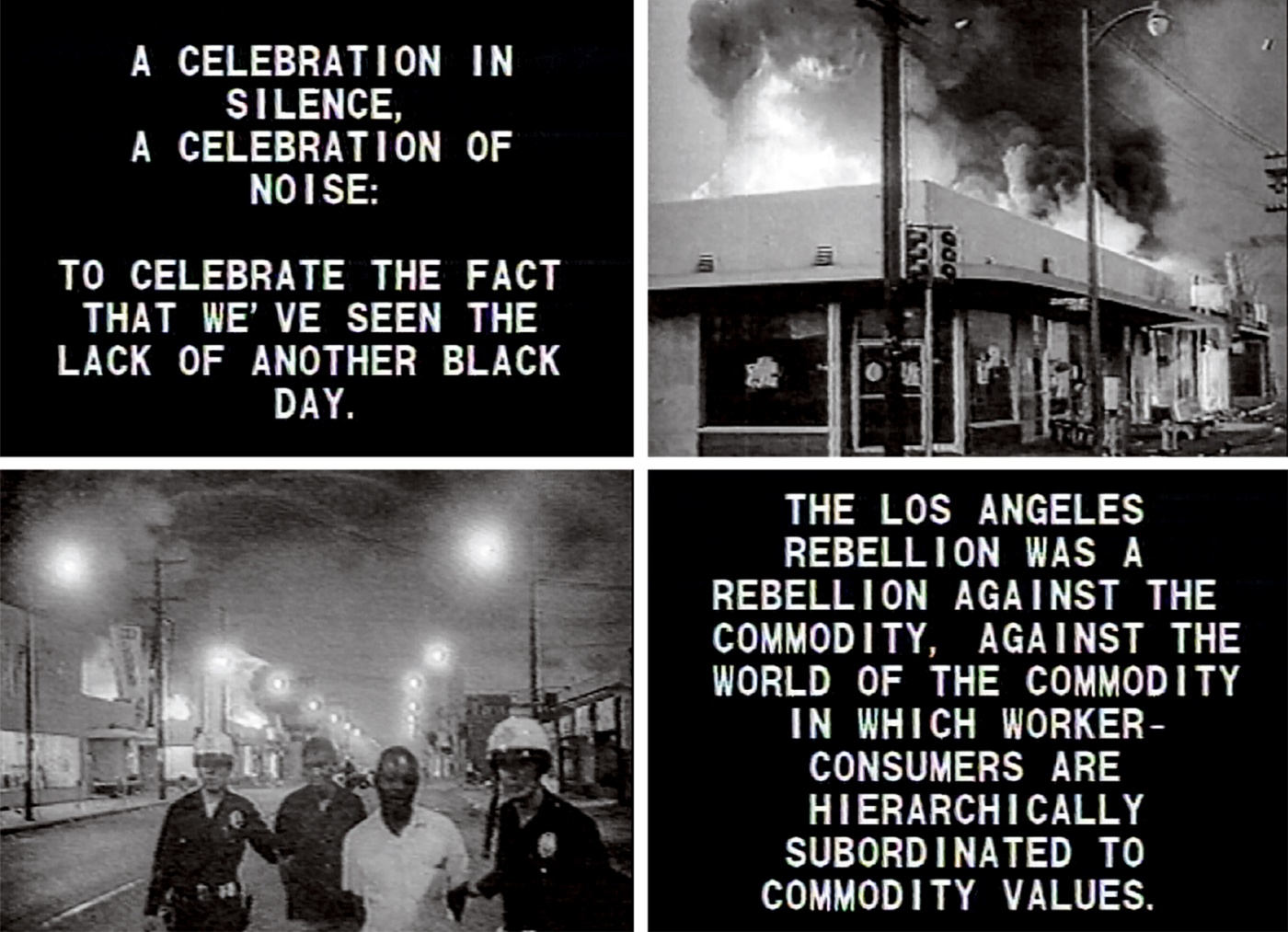

An acclaimed media artist and longtime professor in the department of modern culture and media at Brown, Cokes gained early recognition for Black Celebration (A Rebellion Against the Commodity) (1988), a reconsideration of the urban riots of the ’60s. Remixing newsreel footage of unrest in Watts, Newark, and other Black neighborhoods across the U.S. with appropriated texts from culture theorist Guy Debord, artist Barbara Kruger, and Depeche Mode’s Martin Gore—to the snarling industrial music of Skinny Puppy—Black Celebration presents an alternate take on events from a Black perspective. Rather than representing the unrest as irrational or criminal, it’s seen as an understandable rebellion against racial and economic injustice.

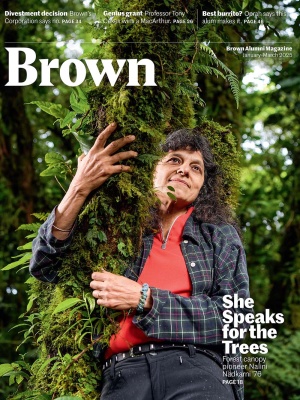

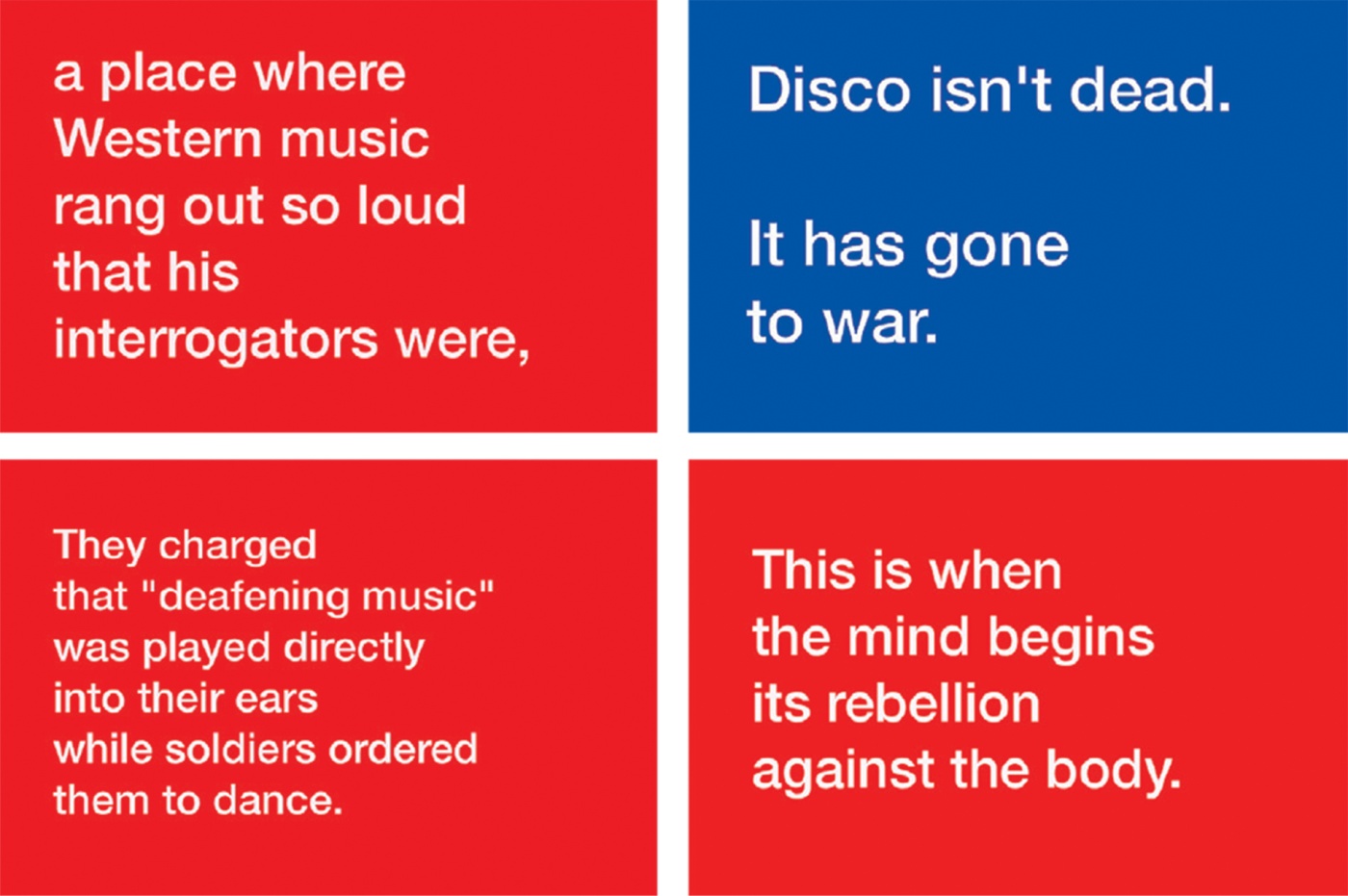

Cokes’s work since, acclaimed and exhibited widely—Whitney Museum of American Art, Museum of Modern Art, Paris’s Centre Pompidou, L.A.’s Redcat—examines charged subjects from Morrissey’s fascist bent to disco music’s use for torture at Abu Ghraib, Trump’s failures on Covid, and Elijah McClain’s death at the hands of Denver authorities.

The rise of the Black Lives Matter movement in the twenty-teens saw Cokes and his work gain new attention and respect. He attributes it to the works’ increased “legibility.” A lot more people get where he’s coming from now.

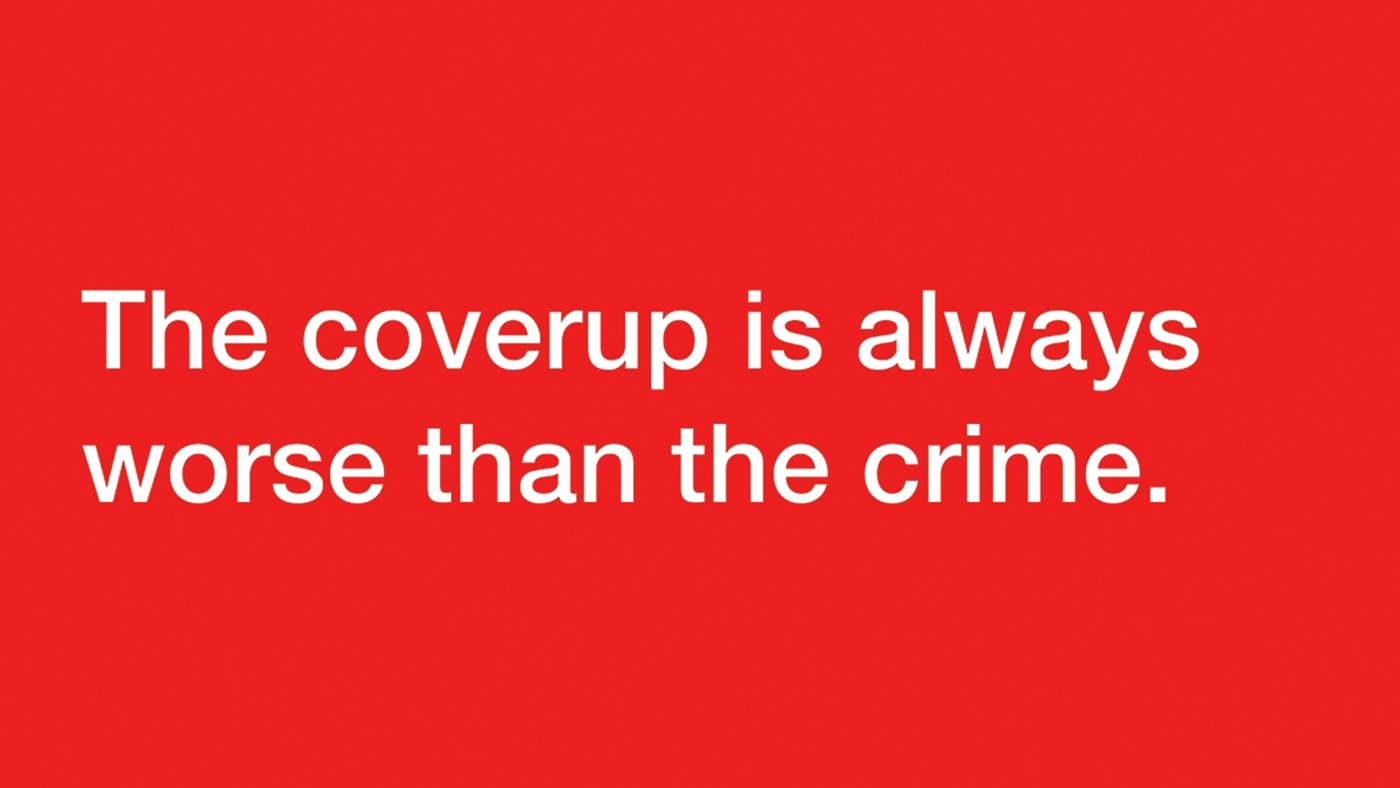

And in an era of repeated (and repeated, and repeated) political lies, distortions, and disinformation; amid persistent, pernicious social narratives; Cokes’s ongoing social critique and reframing of historical events and moments feels almost like deprogramming. Just months ago it earned him a 2024 MacArthur “genius grant.”

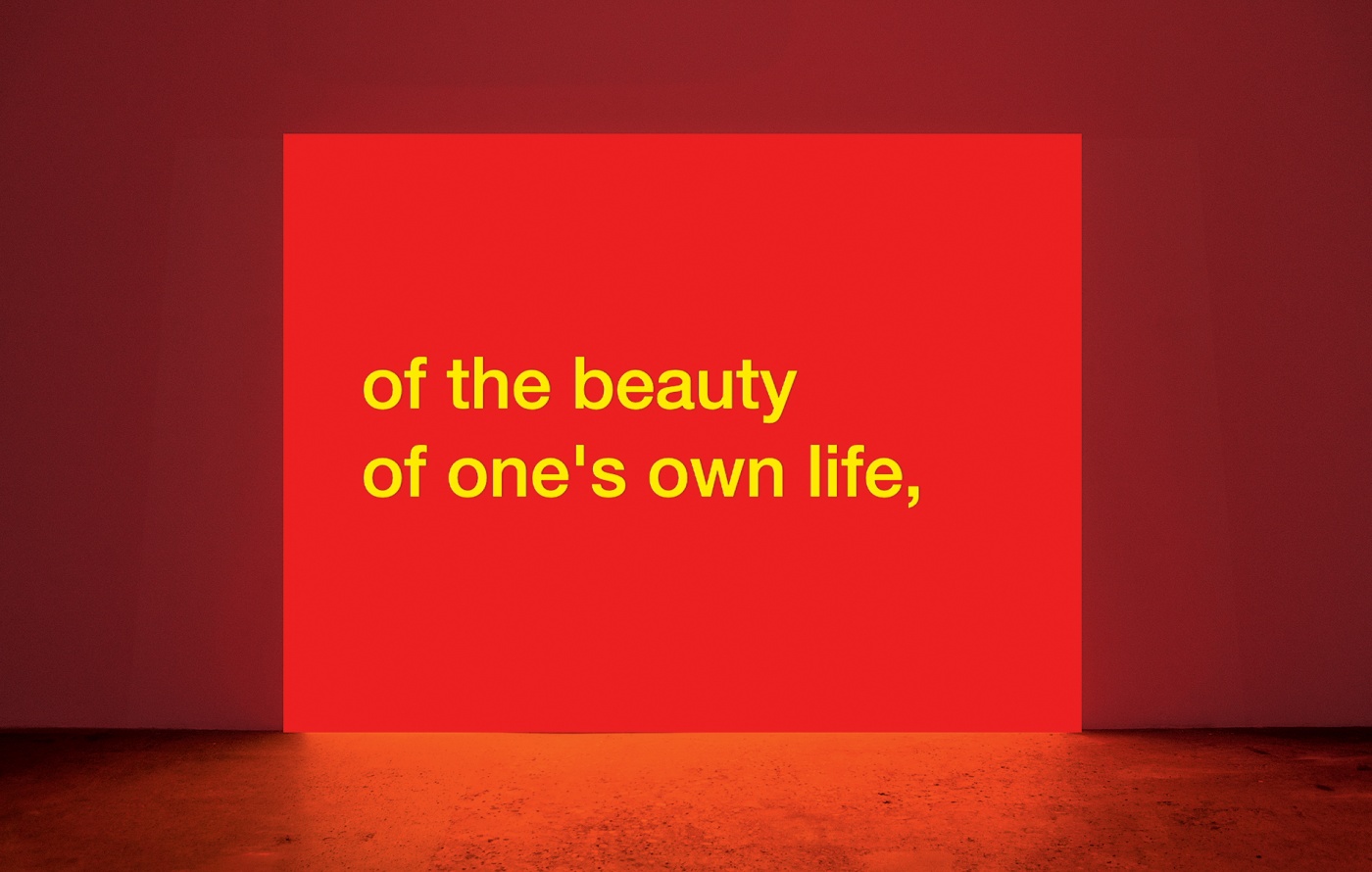

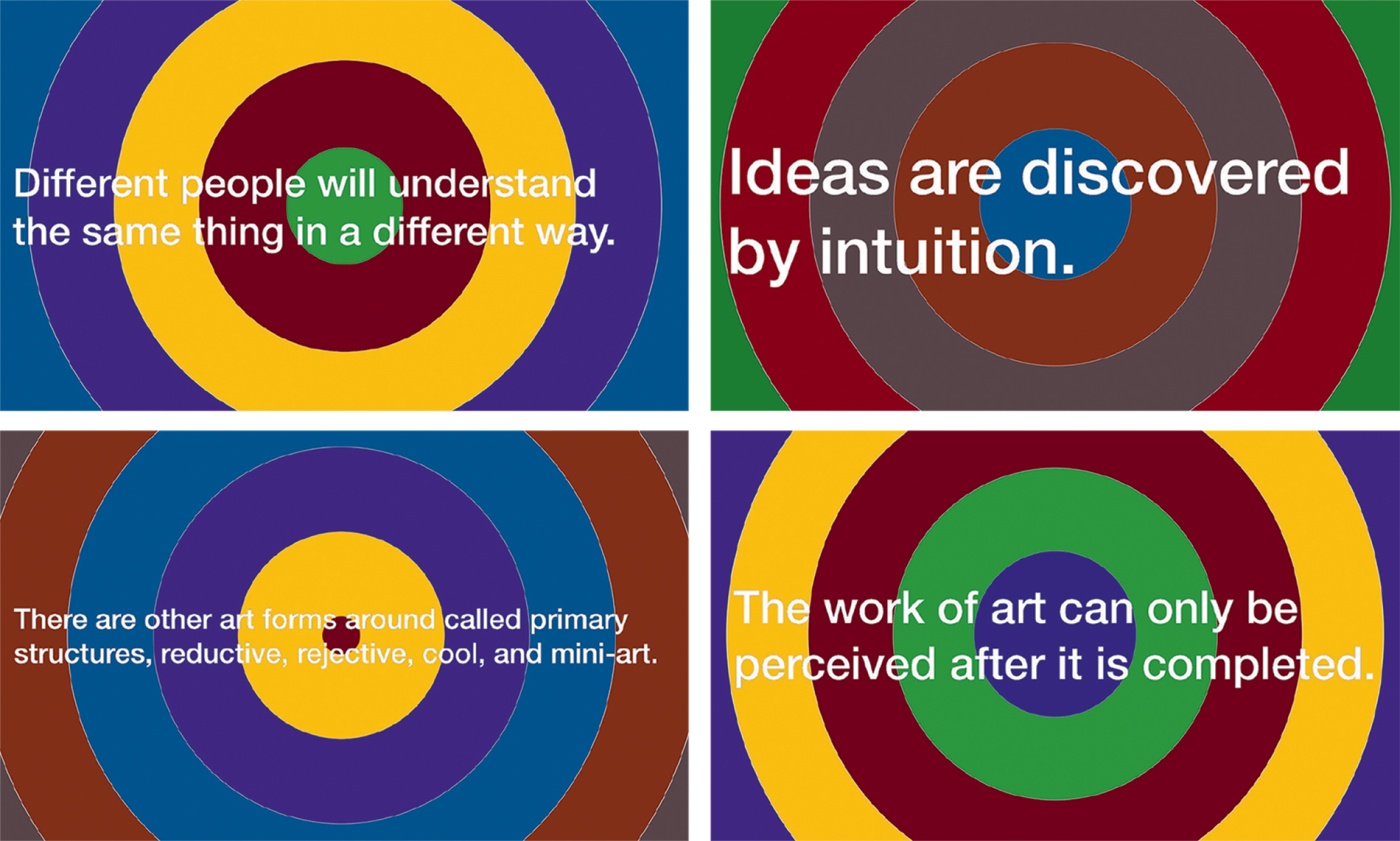

Tony Cokes’s works are neither over-complicated nor overbearing. While they can appear on big screens and even giant outdoor displays, they’re typically minimal video slideshows of basic text, excerpted from the words and works of thinkers, pols, pop stars, and public figures, set to music familiar to contemporary ears.

“I like [the work] to be simple or appear simple so it can be complicated in other ways,” Cokes says. By the ways in which we process it, he means. By the competing thoughts, revelations, and impulses it brings up.

The effect of bright, often provocative statements moving past onscreen—out of context, familiar-seeming but elusive—in counterpoint to unexpected music and lyrics, can alter how we process, how we register what was said. THAT was said? Insights may arise, confound, compete with reactions based on prior thinking.

“Part of the reason I do the work is so people can have that little lack of knowledge, the realization that ‘Oh, I’ve seen this before... But maybe I didn’t... Maybe I didn’t really see it, or all its implications....’ As opposed to, ‘I understand this and it’s time to move on.’”

Works pull in different directions. You may find yourself grooving to a Bee Gees tune or Metallica track as you read of its use in torture by U.S. forces in Iraq. The effects can be dizzying, disconcerting...or not: a toddler may pull up nearby dancing with delight, innocent to pop culture’s incessant unsettling contradictions.

“Few artists have developed and rigorously maintained a signature style of artistic address as powerfully affective as Tony Cokes,” says Jordan Carter, curator and codepartment head of N.Y.C.’s Dia Art Foundation. Carter organized Dia Bridgehampton’s vibrant, site-specific June 2023–May 2024 exhibition Tony Cokes.

“His fusion of sonic beats, trenchant text excerpts, and vibrant color backdrops are instantly recognizable, yet never predictable in terms of content or scope,” Carter says. “Truly a remarkable accomplishment.”

Cokes never tells us what to think about any of it, never moralizes. He presents material: journalist Ronan Farrow on Britney Spears’s conservatorship to a remix of her bangers, philosopher Judith Butler on Covid’s social implications set to Joy Division’s “Exercise One.” The conclusions are ours to draw. He does, however, intend for pieces to reverberate, to prompt further reflection.

“A lot of [media] is meant to result in an immediate understanding,” Cokes says. “I try to postpone that to some extent, so that it’s just not all graspable at one time.”

As a post-conceptualist, a classification Cokes approves of, his work is all about ideas. Not only the ideas the works are based on or concerned with, but our ideas in response to them, our reactions and reflections after the fact. They’re arguably its most important element.

Ideas have always driven Cokes. Understanding how he’d create an art practice around them, though, took some time. Coming up as an undergrad at Goddard College, he had no clear idea of where his creative bent was leading.

“I felt more ideas-driven than visually driven,” he says. “I never considered myself particularly visual. I didn’t study art in high school.”

Interested in media, he enrolled in film and broadcasting school but soon dropped out, partly out of frustration with limited access to equipment as an underclassman, but also because he already knew he wasn’t interested in working conventionally in those industries. His ambivalence may have been colored by what he experienced growing up in Richmond, Virginia.

“There’s always been a gap for me between the world as represented, say, in film or television, and my daily life,” Cokes says. “I’ve always tried to understand how the differences were constituted, why I felt included or not included in the material I was accultured to.”

Opting for a BA in creative writing and photography (which held its own drawbacks for him due to conventional ideas of the time), Cokes went on to earn an MFA in sculpture at Virginia Commonwealth University, mainly because the program was open to talking about and exploring his ideas.

He experimented with various forms of art-making—writing, performance. But an autobiographical approach felt imperative at the time and he wasn’t interested. He found the materials he created for the work far more interesting: he wanted to work with media, just not in traditional forms.

“I discovered that maybe I’d be an artist or someone who’s interested in [media and] visual culture, but not necessarily interested in a disciplinary approach to them.”

And it wasn’t just the art. Cokes was interested in social conditions and stakes and implications of artwork and art practices.

Invited to the Independent Study Program at the Whitney (which credited toward his master’s) Cokes found mentors in artist Martha Rosler—whose own work and early DIY ethos were foundational—and critic Craig Owens—whose theoretical approach to art works, particularly those of women, would inform his own practice.

Cokes found additional, early inspiration in Dan Graham’s Rock My Religion, for its maverick theorizing and almost personal-essay-in-clips form, and Richard Serra’s video piece Television Delivers People for its use of text and integrated muzak soundtrack.

Benefiting from the thinking of such artists on his way to becoming a pioneering artist in his own right, Cokes took up mentoring and inspiring students early on. He joined Brown’s faculty in 1993 and remains a fixture in the department of modern culture and media 30 years later. For many artists, teaching is a fraught necessity. For Cokes, it’s rewarding and informative.

“Far from being an energy drain, I’ve learned a lot from students,” Cokes says. Meeting with people to discuss his own work always energizes his practice. Returning that favor for his students does the same.

“Some of my best friends and collaborators are former students,” Cokes says. One such ex-student, choreographer Andros Zins-Browne ’04, most recently performed a day-long response to Cokes’s 2024 Dia Bridgehampton installation. In 2001, Cokes cocreated “3#” and “6^” for the Pop Manifestos series with former students Seth Price ’97 (a post-conceptual artist) and OK Go’s Damian Kulash ’98.

“I love Tony!” Kulash exclaims, when cold-called on a Saturday morning for a chat about Cokes. They’re the first words out of his mouth. The next are: “I just can’t do it now, I’m making a film... because of Tony!”

Kulash’s enthusiasm for Cokes is shared. Cokes’s first solo show in Portugal opened at Batalha Centro de Cinema in Porto at the end of last year. He has upcoming solo shows at

Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein (Spring ’25) and Hannah Hoffman, Los Angeles (Fall ’25), with even more group shows and festivals opening in between.

The Porto exhibition acted as part two in a “portrait series” on critic and culture theorist Mark Fisher. Cokes regularly creates works in series and his portraits represent a growing body of his work. Not portraits in the traditional sense, Cokes evokes his subjects with words or writing about them, relying on viewers’ memories and imaginations to complete the portraits.

“I’ve been thinking a lot about how people’s words or words about them can be portraiture. It’s a little easier to wrap your head around than to say these are quotations by and about a figure.”

Wrapping our heads around ideas and unresolved issues remains central to Cokes’s work, and now, he’s getting some help with it from his genius grant. Cokes will use part of the $800k award to take on an ambitious project, long-simmering in his mind, focused on Factory Records, the U.K. punk and new wave era label behind Joy Division and New Order.

Brad Miskell is a writer and artist living in Ojai, California.