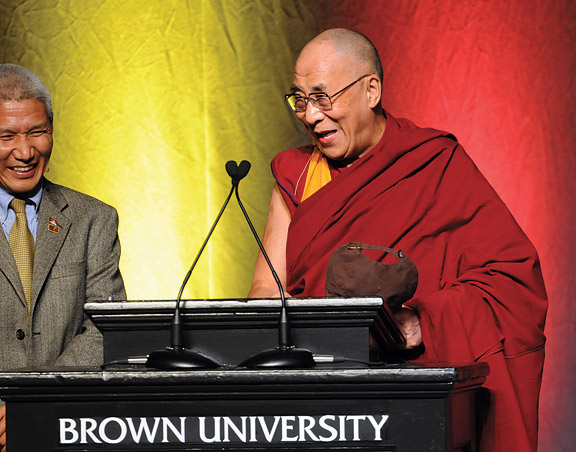

Long lines of people waited to pass through metal detectors at the Rhode Island Convention Center in downtown Providence on October 17. Absent, though, was the impatience so often evident when similar lines at airports grow too long. Why was everyone so sanguine? They were waiting to see the man Brown had invited to address them: His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama.

By then the Dalai Lama had slipped on a Brown baseball-style cap and

was peering out at the audience with his photogenic smile. His talk, a

Stephen A. Ogden Jr. ’60 Memorial Lecture on International Affairs, was

a wide-ranging meditation on “A Global Challenge: Creating a Culture of

Peace.” The word talk seemed a particularly apt description: he riffed

informally on his subject for almost an hour and a half without a

single piece of paper in sight, navigating his way skillfully through

noble sentiments, anecdotes from his world travels, a history of the

last hundred years, and offhand insights into international relations.

He warmed up by presenting two truisms: that human beings have more in

common than they often realize, and that violence leads only to more

violence. Connecting the global to the personal—a link that ran

throughout his lecture—he tied his theme of global peace to the simple

happiness each of us seeks. Freedom from violence in our inner lives as

well as our outer ones, he hinted, is really all that each of us wants.

“Peace is not something sacred,” he said. “We want that peace because we want a happy life.”

At seventy-seven years old, he continued, he has lived through “a

century of bloodshed” that included World War II, two atomic bombings

of Japan, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the nuclear arms race, and

various civil wars. This century’s terrorism, he said, is a“symptom of

last century’s mistakes.”

Then the Dalai Lama paused and said to his audience, “I want to address

mainly the youth.” He asked for a show of hands by people under thirty,

and most hands in the room went up. How many were under twenty, he

wanted to know, and how many were fifteen or less? These, he said, all

made up the generation of the twenty-first century. To the audience

members in their seventies, sixties, or fifties, he said, “We are the

generation of the twentieth century. So our century is gone.”

Now the most important question, he continued, is what kind of century

will the twenty-first be? The responsibility for this century rests “on

younger people’s shoulders. Not my shoulders. For me it’s time to

relax. We are watching you.” Yet what effect can one person have on the

powerful currents of history? To answer that question, he argued, one

has only to look at the popular movements that have succeeded in modern

history. “During the 1960s and ’70s,” he said, we faced the “threat of

nuclear holocaust. That is gone. Not by force, but by popular

movement.” The Soviet Union dissolved because of its own people. In the

Philippines, President Marcos relinquished power because of that

country’s own popular movement.

Although the Dalai Lama’s talk ranged widely over international relations, science, and religion, what united it were two threads: his own unwavering optimism and his Buddhist belief in compassion. He hoped the twenty-first century would be known as the century of compassion, he said, when people would go beyond their own self-interest to look at others and say, “Their problems are my problems.

Their happiness is my happiness.”

As for his optimism, it emerged most vividly in the Dalai Lama’s

description of the audience he had with Queen Elizabeth in 1996. (“Very

nice lady,” he said.) He recalled that he was eager to ask the queen

one thing: “Since you observed almost all of the twentieth century,

would you say we are becoming better, worse, or the same? Without

hesitation, she said, ‘Better!’ When she was young no one talked about

civil rights or the right to self-determination,” and those are

universal principles today.

Tolerance, compassion, optimism: these are the values he kept returning

to, values that may have religious roots but that must be promoted even

more strongly in secular culture. “Secularism,” he said, “is not

hostile to religion.” Even some animals practice limited altruism, not

out of some vague idealism, but for their survival.

After answering a few videotaped questions, the Dalai Lama, never one to appear pretentious or take himself—a world religious leader—too seriously, ended on a mischievous note. “Please think [about] some of my points,” he said. “If you feel some interest, then think more. And you yourself investigate these things. And then try to share with more people.” But if you feel these points are not relevant, he continued, “Then forget. No problem."