The BDH in the News

From the Archives: A century after its birth, the Brown Daily Herald is perennially the subject of the news as well as its bearer

This article originally appeared in the Brown Alumni Monthly in April 1992.

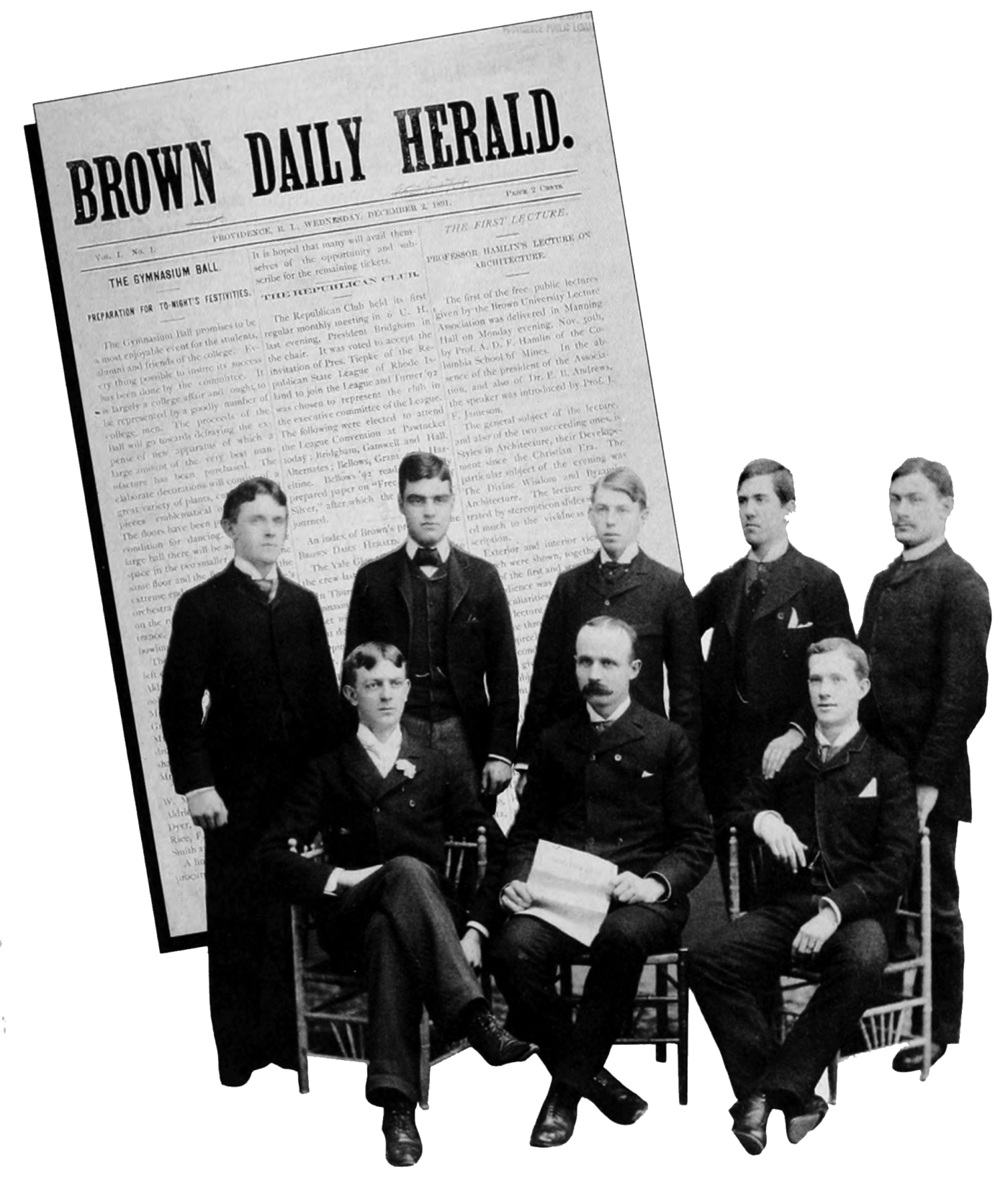

On December 2, 1891, the Brown Daily Herald published its first issue. Within three decades, the Herald came to dominate the journalistic competition on campus–its greatest competitor of the day, the weekly Brunonian, fell by the wayside in 1918.

Few things have been constant during the century in which Brown has had a daily newspaper. The Herald has been a student activity in Faunce House and an independent corporation renting office space on Angell Street. It has gone from using a Providence typesetter to an almost completely self-contained system using desktop publishing on Macintosh computers. However, in one respect, the Herald has stayed the same: since its early days, it has maintained its position as the University’s single most important student periodical, crowding out competitor after competitor and defining student journalism at Brown.

When the Herald was inaugurated, Brown was the smallest college in the United States to boast a daily newspaper; even now it remains among the smallest to have one. When the new daily first appeared, the rival Brunonian promptly published a three-page editorial bitterly attacking the new publication as an unnecessary waste. “There is not sufficient news in a college our size to support a first class daily,” it argued, “and anything less is an expensive luxury [sic] as well as a misrepresentation of the college.”

In the following century, the Herald has remained both the subject of and a participant in a wide range of disputes. Particularly since the 1960s, the Herald has aggressively helped to shape debate on campus; in times of relative quiet, the newspaper itself has often become the topic of controversy.

Before 1960, the Herald tended not to play an activist role, but there are notable exceptions. In the 1930s, the Herald’s editorial board led a “War Against War” movement on college campuses nationwide, urging students to sign a pledge stating that they would participate in a war only if the United States were invaded. This stand led the Rhode Island House of Representatives to investigate the Herald for disloyalty and possible foreign or Communist influence. Several thousand students nationally signed the Herald’s pledge, and the legislators ultimately dropped their investigation. (Subsequent anti-war editorializing–the Herald opposed both the Vietnam and Persian Gulf Wars–has sometimes brought criticism, but has never again yielded charges of “conspiracy against the United States and perhaps . . . treason,” as Representative W.A. Needham ’15 characterized the War Against War movement.)

Social issues sometimes dominate the campus, and the Herald historically has been in the thick of those debates. M. Charles Bakst ’66, a former editor who is now government affairs editor at the Providence Journal, recalls that, in the mid-sixties, the newspaper’s relationship with the administration “got a little stormy” because of the Herald’s discovery that Health Services was making birth control pills available to some Pembroke students. He proudly remembers the front-page story as “a strong example of our aggressiveness, of the newspaper's ability to stir up controversy on campus.” The coverage forced issues of sexuality at Brown into the open, ending the University’s attempts to adjust to the times covertly while maintaining a conservative stance in public.

“Several years ago,” Bakst continues, “I was invited to speak at a Brown seminar on ‘The Pembroke Birth Control Scandal of 1965.’ I had the most difficult time explaining to my audience of students why the birth control pill was a major story. They just couldn’t understand the degree to which social issues dominated the campus–birth control, parietals, whether Pembroke students would be allowed to live off-campus in apartments, and so on.” In a time when social issues pertaining to student life often divided the University, the Herald’s reporting and its editorial stance frequently focused and shaped the debate.

Former executive editor Matthew Wald ’76, a member of the paper’s governing corporate board and a reporter for the New York Times, suggests, “Now the Herald is more of a forum for student opinion than it was when I worked on it,” noting the presence of regular op-ed columnists. Last year’s editor-in-chief, James Kaplan ’92, sounds a similar note by insisting that a primary purpose of the Herald’s news coverage is “encouraging a dialogue on campus” by reporting on the activities and ideas of different groups. Also suggesting a shift from investigative journalism and aggressive editorial stances to a forum for student opinion is the coverage of the most divisive social issue of recent years–sexual assault and the so-called “rape list.” (In the fall of 1990, graffiti appeared on the walls of women’s rest rooms listing the names of men who had allegedly sexually assaulted women at Brown.) While in Bakst’s day as editor, it was the Herald’s reporters who uncovered the birth control story, the existence of the rape list was first publicly discussed by an op-ed columnist, Sianne Ngai ’93.

Criticism of the administration seems to have followed a similar path, away from news and board editorials, towards op-ed columnists, letters-to-the-editor, and campus activists writing guest columns in the Herald or its chief contemporary competitor, the weekly College Hill Independent, a joint Brown-Rhode Island School of Design publication. During the late sixties, the Herald’s editorial board served as the voice of student dissatisfaction with President Ray Heffner, who resigned after just three years in office. The newspaper was even more vocal in its criticisms of Heffner’s replacement, Donald Hornig. (Once the Herald’s board editorial claimed that “it is no secret that the president has no positive relationship whatsoever with students and only slightly more of one with the faculty. Even administrators lack faith in the president's office.”) However, when former Dean of Students David Inman came under fire last year for allegedly mishandling sexual assault charges in the disciplinary system, oped columns, letters to the editor, and guest columns led the attacks.

Wald suggests that the Herald merely reflects the atmosphere on campus. “The thinking of the undergraduates towards the administration used to be an ‘us versus them’ mentality, and that included the Herald,” he says. “That’s not the case anymore.”

Whenever the media lose the ability or desire to uncover and stir up interest in the news, they sometimes become the main topic of discussion themselves. While the last several years have certainly not been slow ones for news at Brown, the Herald itself has returned to the spotlight it occupied a century ago when the Brunoniait ran three-page editorials criticizing it.

Today’s critics maintain that Brown is too small a community for a daily newspaper not to become hopelessly entangled in the stories it covers. Just as it could a century ago, the Herald can (and does) argue that much of the controversy surrounding it is artificially stirred up by other publications resentful of its dominance.

Other critics claim that there is plenty of news at Brown–much more, in fact, than the Herald chooses to cover. How those choices are made, and whether there is any recurrent bias in them, form the basis for much of the fire aimed at the daily.

A widespread perception certainly exists that the Herald’s selection of news stories arises from a certain bias. Commentator Todd Seavey ’91 coined the term “BDH Democrats” to refer to the sort of ideas the news and editorial boards are perceived to favor. White, middle- or upper-middle-class, often focused on New York City, and left of center but emphatically not radical, the BDH Democrats draw fire from right and left alike.

Conservative speakers and activities are infrequent at Brown, but those that do get off the ground are sometimes not covered. The family of Karen Bell, a teenager who died from an illegal abortion obtained in order to evade parental-consent requirements, tours the country speaking out in support of abortion rights and in opposition to parental consent laws. When they came to Brown last fall, the event was covered on the front page before and after it occurred. During the same week. Brown Students for Life sponsored an address by a founder of the National Abortion Rights Action League who has switched sides and now opposes abortion. The speech was not mentioned in the Herald. Similarly, the visit of prominent leftist scholar Stanley Fish was a front-page story before and after the event. Fish’s frequent intellectual sparring partner, conservative Dinesh D’Souza, had spoken at Brown several months before; his visit produced a resounding silence in the pages of the Herald.

The Herald is also frequently accused of ignoring events and issues of importance to students of color and to lesbian, gay, and bisexual students. Danny Horn ’92, a Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Alliance staffer, says wryly that “I really can’t comment on the Herald's coverage of LGB issues, because it is basically nonexistent.”

A longstanding animosity exists between the newspaper and African- and Asian-American student groups. “There are two problems,” says Anu Gupta ’93, “and I think they’re related. One is the fact that the Herald gives so little coverage to issues of concern to the Third World community, so little coverage to events sponsored by Third World groups. The other is the fact that there are so few people of color working on the Herald.” Gupta, an activist who has been involved with the Undergraduate Council of Students and, more recently, acted as spokesman for the Asian-American Students Association, recently has been one of the most vocal and visible critics of the Herald.

Kaplan, the 1991 editor-in-chief, insists that coverage is not intentionally biased. “You won't ever–ever–hear editors sitting around saying, “I don’t think we should assign reporters to this or that event because I don’t like them.’ In large part, it’s a question of letting us know. For example, the people at Brown for Choice very carefully cultivate a relationship with us–they bring us press releases and call us and make sure we know what they’re doing. We never heard about the Brown for Life thing until it was over.” (Indeed, better publicity subsequently resulted in extensive pageone coverage of a Brown Students for Life-sponsored seminar on February 29, featuring speakers Mary Cunningham Agee, founder of The Nurturing Network, and Carol Everett, a former Texas abortion-clinic head who has switched sides to the pro-life movement.)

Wendy Kahn ’93, 1992 editor-in-chief, carefully states that she doesn't know how articles were assigned under past boards, but suggests that “when the beat system kind of fell apart, coverage of Third World issues may have suffered. The last board brought the beat system back, and we'll be strengthening it even more. We’ve had a beat reporter to cover the Third World community for the last semester; we’re going to keep doing that.”

Kris Renn, assistant dean of students and the administration's official liaison to the lesbian, gay, and bisexual community, suggests that beat coverage might not be enough. She thinks “the Herald gets a bum rap” about not covering events; “the sponsoring groups have to let them know. You can’t assume that just because you’ve bought an ad through the business staff that the editorial staff will have time to read the ad and assign a reporter to cover your event. The responsibility is on the group. On the other hand, things like feature reporting and more in-depth coverage of issues, as opposed to events - well, I'd like to see more of that sort of coverage of LGB issues.”

Bias is a serious charge against a newspaper; inaccuracy is a worse one, and is leveled frequently against the Herald. Letters to the editor claim misquotes or note misstated facts; the Organization of United African Peoples, for example, was referred to as the Organization of United American Peoples, a blunder cited by Gupta as indicative of the Herald’s apparent lack of concern with Third World issues, and noted sheepishly by editor Kahn to illustrate the need for copy editors who can check for accuracy as well as grammatical mistakes.

One of the most notorious cases involved Professor Abbott Gleason, chairman of the history department. When the late President Howard Swearer announced his resignation in 1988, the Herald quoted Gleason as saying he had “no serious educational accomplishments.” Gleason angrily denied having said anything of the sort. Upon Swearer's death last fall, the newer Herald reporters reprinted some of the comments and statements that had appeared in the resignation articles–including the misquote from Gleason. Gleason notes that “probably every faculty member has been misquoted by the Herald,” but remains angry that such a painful misquote would be used twice.

More recently, in February the Herald ran a front-page story - complete with names and mug shots–declaring that two fraternity brothers had been found guilty of voyeurism. A week later, after a series of communications from the dean of student life's office, the newspaper ran a correction conceding that there had been no finding of guilt in the disciplinary case.

Past editor-in-chief Kaplan acknowledges that accuracy is sometimes a problem, but says that “we try to do better. We wish we could be perfect, but no paper is ever perfect.” Current top editor Kahn observes that it is difficult for editors to be familiar with all of the agencies, departments, administrators, and organizations on campus, but says there is more that can be done. She intends to encourage reporters to call back sources after an article is written and confirm quotes.

Part of the problem seems to stem from Brown’s combination of big-city expectations with what is essentially the environment of a medium-sized town. Kaplan notes that “any time you’re in a small community, like a college, you’re going to have people who are very close to what happens, very close to the facts. That's a difficult position for any newspaper to be in. There tend to be different accounts of the same events. We try to be as inclusive and objective as possible, but different people see the same event in different ways. That's as true for the New York Times as for the Herald, but whereas, with the Times, you have 1.2 million people reading the account of an event that 120 people saw first-hand, with the Herald you have 3,000 people reading our account of an event 300 people might have seen first-hand.” The result, he argues, is that people are much more likely to hear different accounts of an event covered by the Herald than one covered by the Times–and they’re therefore more likely to doubt the Herald’s accuracy.

Ultimately, most arguments about the Herald among students lead to another recent controversy: the newspaper’s subscription contract with the Undergraduate Council of Students (UCS). The contract has been controversial since its beginning in 1985. UCS annually buys a mass subscription to the paper, and every day during the academic year, 3,500 copies of the Herald are left at drop points around campus. The convenience to students is the primary justification given for the contract - there are no individual subscriptions, no need to buy the Herald at a newsstand. Annually, UCS and the business staff of the newspaper sit down and negotiate the following year’s contract: how many papers at what rate, and what bulk discount will be given to UCS-constituted student groups that advertise in the Herald. These negotiations become the focal point for discontent over the paper, and often the most prominent controversy on campus.

Many critics charge that the contract is unfair. All students are forced to pay for the Herald, whether or not they read it. Indeed, virtually no students living off-campus, and a small percentage of seniors overall, read the paper. The critics contend that anyone who wants the Herald should have to subscribe or to buy it daily–as was the case before the contract began - rather than forcing all undergraduates to subsidize those faculty, staff, and on-campus students who read it.

Kaplan charges that much criticism of the contract comes from competing publications (notably Issues Monthly and the weekly College Hill Independent), primarily in order to argue for increases in their own levels of funding.

Three times since 1986, UCS has sponsored a referendum on the contract. Each time, a majority of students voting has endorsed continuing it. Critics were not satisfied, charging that Herald coverage anti lobbying had affected the vote and that the students least likely to vote–those who live off-campus and are least likely to wander past a polling place–are those most likely to be poorly served by the contract.

Initially, both major segments of the student body and much of the corporate board governing the Herald were skeptical of the contract. The Third World Coalition led the opposition on campus; that very opposition made some members of the Herald Corporation skeptical and worried that editors would feel pressure to slant coverage in favor of vocal groups.

Kaplan, Kahn, and Wald all agree that the newspaper’s independence isn’t in jeopardy as long as the editorial board remains vigilant, but Wald admits that “I don’t expect the current relationship with the student government to last forever.”

Commentator Jen Mayer ’91 frequently analyzed “the incestuous little world of Brown politics and journalism.” The phrase captures perfectly what many see as the problem with the contract, and perhaps with the Herald in general. Even if the newspaper’s editorial independence is not in reality jeopardized by the contract, it reinforces a perception that the Herald and UCS comprise a small group of undergraduate writers, politicos, and activists whose activities exist mainly for each other’s benefit.

Even Kahn notes that “the paper has been pretty cozy–maybe too cozy–with the administration and some groups on campus. Our job is to stand apart. A reporter doesn’t want to lose a valuable source by writing a critical article, and an editor doesn’t want to lose some future letter of recommendation–but we can't let those things affect us.”

Kahn goes on to worry about the personalization of journalism in other ways. “When there’s a big debate about one of the columnists, there’s a tendency to talk about them personally, not about the ideas they put forward. That probably wouldn’t happen at a bigger school. At a place like Michigan, the average letter-writer isn’t likely to have ever met the average columnist, and things wouldn't get nearly so personal. Someone like Piper Hoffman [’94, a columnist who discusses feminist issues, or MacArthur White ’91, whose focus was on financial aid and issues of class and who was the subject of an article in the September BAM] would get letters, but they’d be letters attacking the ideas, not attacking them personally.”

Ultimately, this is the question the Brown Daily Herald may have to address: whether at a school as small as Brown, with an even smaller cohort likely to contribute to, read, and care about a daily newspaper, it is possible to “stand apart.” If it is not, the Herald will continue to be a part of the news as well as its chief bearer well into its second century.