Zachary Lazar was five years old when a pair of Chicago hit men murdered his father in the stairwell of a Phoenix, Arizona, parking garage on February 19, 1975. Using a semiautomatic pistol with a homemade silencer, they shot Ed Lazar four times in the chest and once in the back of the head. Then they placed a dime on his forehead.

As a child Ed's son, Zachary, knew none of this. All he could later recall of the day his father died was the hysterical laughing sound his mother made when detectives told her the news and the way she lunged forward and back on the couch like a marionette. "The scream was angry, personal, insane," Lazar writes in Evening's Empire, his attempt to understand his father's life and death. "Almost from that moment, we stopped talking about it. As time passed, there were fewer and fewer occasions on which it made sense to try. To do so was to return on some level to my mother screaming in the living room."

Lazar, the author of the novels Aaron, Approximately and Sway, describes this book as a conjuration, which is an apt description for this hybrid of empathic imagination and meticulous research. Evening's Empire is both a gripping true-crime story and a shimmering portrait of a place and an era. In the 1960s and 1970s, Warren and other developers snapped up huge swaths of barren land in Arizona, then subdivided it on paper and printed up brochures depicting a golf course, a trout pond, and neat little ranch houses. Retirees and GIs handed over their nest eggs, convinced Arizona was the perfect place to spend their final years.

With corruption rampant, Warren realized you needed neither land nor buyers to profit. Matching fake buyers to fake land, Lazar writes, Warren would make a few mortgage payments and then repackage and sell off the debt. To muddy the trail, he'd run it through a few of his companies.

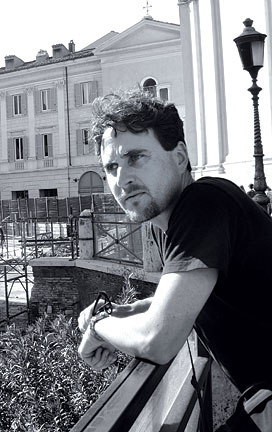

On a personal level, Lazar's book is about discovering who his father was and how he became involved in such a callous business. Ed Lazar was not your average CPA, his son writes; he loved to play tennis with his friends and shoot hoops with the neighborhood kids. He wanted to be a player. It was not greed, but the desire to be in the game that undermined Ed Lazar, his son concludes. Problem was, the stakes were just too high and the players much too fast.Charlotte Bruce Harvey is the BAM's managing editor.