The turning point in his life, Eric Rodriguez says, came after he was arrested. The police had picked him up at school in Fresno, California, and charged the fourteen-year-old with possessing graffiti paraphernalia. He was taken to Fresno County Juvenile Hall—“a scary-ass place” is how Rodriguez ’08 remembers it. Many of his fellow prisoners in the processing unit were drug dealers and gang members. He knew some of these kids from school and he’d always made it a point to stay clear of them. And now here he was among them. “Am I also becoming a criminal?” Rodriguez asked himself.

He was released twenty-four hours later into the custody of his mother, Marisela Laursen. She had been raising her son alone for the past twelve years—ever since his father left when the boy was two. Rodriguez told his mother what she would later learn was true—that he’d been falsely arrested—but she didn’t believe him that day. He expected her to give him a good chewing out or to smack him. Instead, she was silent.

“Say something,” he pleaded as they stood on a corner waiting for a bus to take them home.

“I’m losing hope for you,” his mother said.

As he remembers the incident today, Rodriguez says it was a troubling statement for a boy to absorb. “When I heard that,” he says, “I knew I wanted to change.” He left Fresno for metropolitan Los Angeles, where his mother had a friend in Santa Fe Springs in the southeastern corner of L.A. county. The plan was for him to stay with her for the summer. This would allow him to get away from the friends and relatives who were slipping into the world of drugs and gangs. Several of his cousins had already run afoul of the law; according to Rodriguez, one would later be arrested for armed robbery. “Everybody thought I was crazy to let him go,” his mother says. “The only thing I used to say is ‘I trust my son. I think he’s going to make it.’”

Rodriguez arrived in Santa Fe Springs carrying a large garbage bag full of clothes and a few other possessions. At first life was normal in this friend’s house. Once the summer had passed, he decided not to return to Fresno. But the woman and her husband began fighting all the time, yelling and slamming doors. Rodriguez tried to stay clear of their angry outbursts, but they started blaming their lack of money on the expense of having him living in their house. Then one night, about a year and a half after Rodriguez had first moved in, the husband put a crumpled ball of paper in front of his face and opened it. Inside was cocaine.

“He was really emotional and just started confessing all these things to me,” Rodriguez says. “He said all the problems he was having with his wife were happening because of his cocaine problem.” Rodriguez again felt trapped. This was not the sanctuary he and his mother had hoped it would be. “It ended up being more of the same,” he says. He felt he couldn’t go back to Fresno. He was desperate to escape that world. Rodriguez moved out and started crashing with friends nearby. He did not, though, tell his mother. “He used to tell me everything was fine,” she says. “He kind of wanted to protect me.” When she went to visit him, they typically met at strip malls, taco stands, and fast-food restaurants. She suspected nothing, she says.

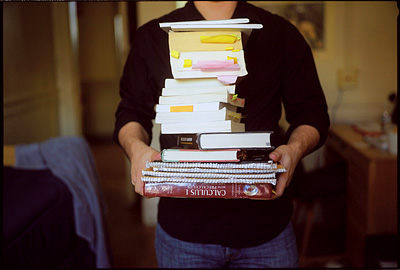

Rodriguez is a likable guy, very social and outgoing, generous and sincere. His friends readily took him in, Rodriguez says, though fearful of overstaying his welcome, he never stayed in one place for more than a few days. He slept on couches or floors, showered only a few times a week, and kept all his possessions in a gym bag—a few changes of clothes, toothbrush and toothpaste, and his school books. On a few occasions, unable to find a friend to take him in, he slept in his high school’s cafeteria. He would stay late for a drama club meeting and never leave. He says no one noticed.

Rodriguez stayed in school by having a friend’s mother sign as his guardian. He worked as a security guard at a Jack in the Box fast-food restaurant. He had no training, but it paid much better than bagging groceries or flipping burgers. His shift ran from nine in the evening to three the next morning. “I would do my homework at the Jack in the Box,” he recalls, “and pray to God nobody robbed the place.”

Toward the end of his sophomore year, he saw a posting for a three-week-long summer class in architecture at the University of Southern California (USC). Because he liked to draw and sketch, he inquired about the class. USC offered him a $1,500 scholarship to attend, but that still left him $600 short. He went down to Santa Fe Springs City Hall and asked if the city might give him the money. Not surprisingly, a receptionist told him no. She told him to ask his school for the money. He did so, but was turned down. He returned to city hall, where his predicament had by now drawn the attention of city officials. One day, while Rodriguez was at city hall pleading his case, the mayor, Betty Putnam, walked by. When he told her why he was there, she invited him into her office. “I told her,” Rodriguez recalls, “that if the city really wanted to help its students, this was its shot.” A few weeks later, the city council voted to give him the money.

The class was a revelation. It wasn’t so much what Rodriguez was being taught. He was in an entirely new world. He was in a university, sitting among hardworking and occasionally wealthy students, and to his surprise, he found he was just as smart as they were.

“I felt a huge sense of empowerment,” Rodriguez says. “I realized I really could do it.” When he returned to high school in the fall, his grades shot up. He enrolled in several honors and advanced-placement classes. His senior-year project was a report on the American bald eagle. This time, Putnam gave him money out of her own pocket so he could travel to a bird sanctuary in Alaska and observe the eagles firsthand. The project earned him high honors. When he graduated in 2001, his classmates voted him Most Likely to Make the World a Better Place.

A few months later, after watching the terrorist attacks of 9/11, he turned his attention to the military. Not only did he feel the need to join the fight against terror; he believed the military could give him what his upbringing had denied him. “I lacked the amount of discipline required to do good in school and life,” Rodriguez later wrote in his admission essay to Brown. “I hoped that the military would help me gain enough self discipline in order to prosper.”

There was another factor, he says. He felt he needed to prove his family’s commitment to the United States. His mother had arrived in the country from Mexico and his father from Cuba; Rodriguez says his seventh grade teacher told him, “You’re Mexican. You’re not really American.”

“I thought if I joined the army,” Rodriguez says, “I could go and do service to the country and no one would ever, ever question my family’s integrity. I’d make it clear I was willing to give up my life for this country.”

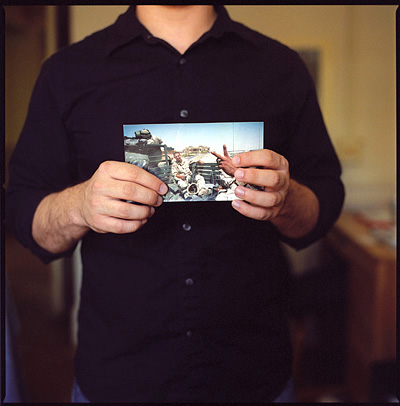

He never expected to wind up in Iraq. But he arrived there as a U.S. Army reservist in 2003, when the war was still young. Iraqis were friendly, but amenities for the troops were nonexistent. “There was nothing,” Rodriguez recalls. “No showers, no bathrooms. You had to burn and bury your own feces.” He and his platoon slept out in the open air under the bleachers of a soccer stadium in Balad, about fifty miles north of Baghdad. It was still possible to move freely among Iraqis, and Rodriguez helped build schools and distribute equipment for basic hygiene and medicine—toothbrushes, Band-Aids, and antibiotics. As the Iraqi resistance grew, he moved into intelligence, building relationships with citizens in the hopes that they would tip him off to the rebels’ whereabouts.

Once, Rodriguez was driving a Humvee when one of the soldiers spotted a few stray pieces of metal on the ground. The soldiers realized they were in the middle of a minefield. A few got out and guided Rodriguez and the rest of the convoy ever so slowly to safety. In his Brown admission essay, Rodriguez later wrote of the incident:

My life did not seem to flash before my eyes, instead it actually passed by quite slowly. That afternoon, I reminisced about various images and memories that I hold very dear: my mother holding my hand on the RTD—also known as the Metro Bus—when I was a boy, my sister teaching me how to make pancakes that we would always end up eating raw, my little niece saying “my uncle is silly,” my friends laughing when I slid across the ice rink on my stomach, the girl that said she loved me and left me, the girl I said I loved and left, the people that said I was going to change the world, the people that gave me the world because they believed that I could change, and lastly, how much I did not want to go and how much I begged God not to take me right then and there.

Being in Iraq put everything in perspective, Rodriguez says—“I knew what I wanted. I wanted to succeed academically. I wanted to go to a four-year university. Nothing was going to stop me.”

He returned to the United States in mid-2004 and visited his mother in Fresno. There was a man in her apartment he didn’t recognize.

“Who’s that?” Rodriguez asked.

“That’s your father,” his mother answered.

“I didn’t know him,” says Rodriguez. “I didn’t want to get to know him.”

But his mother, who was then in her early forties, felt differently. She had decided to live with him again. “I want you to know where you came from and to know your father,” she told Rodriguez. “Yes, he’s made a lot of mistakes but everyone is entitled to forgiveness.”

A few days later, Rodriguez tried to give his father a hug. His father shoved him away. “It reinforced the idea that he didn’t want me,” Rodriguez says. “He rejected me at birth. Now he was rejecting me again.”

Rodriguez’s sole focus was his education. He started by applying to Rio Hondo Community College in Whittier, California, just south of Los Angeles. He was accepted and decided to major in liberal arts. While Rodriguez was in Iraq, his platoon had received a shipment of school supplies bought for Iraqi kids by students at Pepperdine University back in California. The students had raised $10,000, and Rodriguez had been one of the soldiers charged with distributing this gift. He was also given the task of presenting the students with a certificate of appreciation after he returned to Los Angeles.

At Pepperdine, Rodriguez met Dan Caldwell, a professor of political science and a Vietnam-era veteran. Rodriguez told Caldwell about his desire to go to a four-year college, and Caldwell offered his assistance and guidance. “I feel,” Caldwell says, “a responsibility and a desire to help veterans who served in very difficult circumstances.”

Rodriguez asked Caldwell about the possibility of applying to Ivy League schools. “It’s worth a shot,” Caldwell recalls telling him. In the early 1980s, Caldwell had been an associate director of Brown’s Center for Foreign Policy Development, which later became the Watson Institute for International Studies. He wrote Rodriguez a glowing recommendation to Brown.

When his acceptance letter arrived, Rodriguez says, “I was so overwhelmed emotionally. To go through all this struggle and hardship and then there is this sign that says, ‘You’re in. You’re one of us. Welcome to the community’—it was the greatest feeling ever.”

Rodriguez arrived at Brown in the fall of 2006. A few months later, he was walking around the Brown campus when he spotted President Ruth Simmons walking the other way. He has no qualms about approaching well-known strangers, so he crossed over and started up a conversation. Rodriguez told Simmons a little bit about his background. Simmons, who had also struggled with poverty as a child, invited him to an upcoming dinner at her residence on Power Street. Salman Rushdie would be there.

Rodriguez says Rushdie talked to him about death. Rodriguez says he told the Indian-born author about his experiences in Iraq and Rushdie responded by reflecting on what it was like to live under the death threat issued against him by Iran. “‘Death gives you so much clarity,’” Rodriguez says Rushdie told him. “It’s different when death isn’t this abstract concept, but right there for you.” A few months later Rodriguez went to another dinner at Simmons’s home. This time the guests were the former presidents of Brazil and Chile.

Still, Brown has not been easy for Rodriguez, who is scheduled to graduate in May with a degree in international relations. He has had to learn some of the writing and research skills his classmates learned in high school. His mother, who hadn’t heard of Brown before her son got in—she has yet to visit campus—was surprised to learn that many Brown students are wealthy. “Oh, I hope he doesn’t feel uncomfortable around them,” she said. Rodriguez says she has nothing to worry about. He has found Brown to be a welcoming place.

Rodriguez is still not sure what he will do after graduating this spring. He plans to work for several years in government—at what level and for whom he doesn’t know yet—and then would like to go to Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government to study public policy. “A few years ago I would never have thought of Harvard or even Brown,” he says. “But now I do. I’m aiming higher.”

Lawrence Goodman is the BAM's senior writer.

Photographs by Kathleen Dooher.