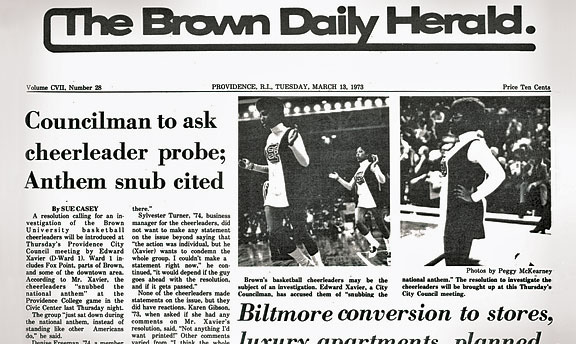

San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick created a stir this football season when he kneeled during the national anthem to protest what he believes is the oppression of non-whites in the United States. Forty-four years ago, on March 8, 1973, before a basketball game between Brown and Providence College at the Providence Civic Center, African American cheerleaders for the Brown basketball team created a similar stir when they remained seated during the national anthem. The Providence City Council quickly passed, unanimously, a resolution of condemnation. “The Civic Center was built by Americans for Americans,” one council member said at the time. “If [the cheerleaders are] not going to act like Americans, we don’t want them there.”

“I chose to stand for the national anthem at the civic center on the night the Brown cheerleaders chose to sit. Their choice was not against the law and did not abridge my choice. I stood because I have seen much of life, and I know that there are very few countries in the world where those two choices could live together in the same arena. America has been one of those countries. That is what America is all about.

“Sadly, the council’s sorry decision has drained me of a little more faith in this country. I have decided that I will no longer stand for the national anthem in this city until the resolution is rescinded and real meaning is restored to the song.”

When reached by phone this November, Denise Freeman Hawkins ’73, the captain of the eight cheerleaders, said she was surprised by the city council’s reaction to their actions. Far from believing they were making a shocking statement, she recalls, the cheerleaders were just joining what most black students around the country were doing at the time. “It was the norm that black students didn’t stand for the national anthem,” she says. “Protests were a commonplace event.”

The practice of black protests at sporting events went back at least to the 1968 Summer Olympics, when Tommie Smith and John Carlos, the gold and bronze medalists in the 200-meter event, raised their black-gloved clenched fists as the national anthem played. At the 1972 summer games, Vincent Matthews and Wayne Collett, the gold and silver medalists in the 400 meters, turned their backs as the anthem played. In fact, by 1973 sitting during the national anthem had become so common during athletic events that Brown had stopped playing it before games.

“That night [in March 1973],” Hawkins recalls, “we went to the Civic Center, and we were sitting there waiting for the game to start when the anthem started. We were surprised. What should we do? We decided to stay sitting.” The phrase in the anthem that irked African Americans at the time was the “land of the free,” which many blacks believed to be untrue, given the legacy of slavery.

Afterward, the cheerleaders kept a low profile as letter writers excoriated them in the pages of the Providence Journal and in other newspapers and as alumni threatened to stop donating to Brown. “I don’t want to make more of [the protest] than it was,” Hawkins says. “But the response was enormous. There were people who had very vitriolic things to say about us. There was some concern for our well-being. I think Brown was glad we didn’t make a statement about it all.”