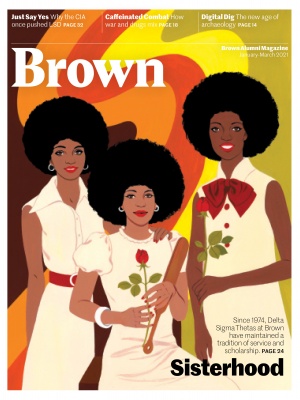

Black Girl Magic

In the wake of the 1968 Black Student Walkout, a chapter of the politically engaged, storied Black sorority Delta Sigma Theta was born at Brown.

By the time Dr. Judith Sanford-Harris ’74, Lydia Boddie-Rice ’76, and Vivian McCoyCade ’74 attended Brown, one of the key demands of the University’s historic 1968 Black Student Walkout had been met: increased African American enrollment. The young women were part of a thriving Black student body that had carved out a significant presence on campus.

Sanford-Harris was a member of the Black Chorus of Brown University, founded by two of her friends. She was also a vocalist in Black Spectrum, a student band aptly named for the range of African American music styles in their repertoire. “Some of it was R&B and funk, some of it was jazz and blues,” Sanford-Harris recalls fondly. “It was pretty cool, and we toured all over New England.”

Boddie-Rice, with a dual major in psychology and art, gravitated to expressive pursuits. “I carved out an identity as a renaissance student of the arts and immersed myself in Black culture,” she says of her interests back then. “I was very much a part of Rites and Reason Theatre,” founded by noted playwright and African American Studies professor George Bass. “He formed a strong, safe, connected refuge for us to celebrate and explore our roots.” She also sang in the Black Chorus and danced and toured with the school’s African American dance troupe.

Cade was a cheerleader for Brown’s basketball team—a squad that didn’t exist until some of the Black female students who were cheerleaders at their respective high schools took the initiative and formed one at Brown. All three women recall how the Black students, still relatively small in number, were a tight-knit group during those years.

“We were always together in some form or fashion, whether it was studying, playing bid whist and spades at Afro House, or eating at the Ratty,” Sanford-Harris remembers. Moreover, says Cade, “As students we supported each other.”

Additional support came from newly hired African American faculty and staff, another post-Walkout gain. “There were two Black deans on campus, and they were a liaison between us and the rest of the university administration,” says Sanford-Harris. “They were a lifeline when we needed it.”

One dean in particular, a charismatic woman named Nanette Lee Reynolds, was popular among the Black female students. “She was exquisite, and very involved with the student community,” recalls Boddie-Rice. Reynolds was also a member of Delta Sigma Theta, the largest African American sorority in the United States. Working with the Providence alumnae chapter of the sorority, she helped to establish Lambda Iota, a citywide, collegiate chapter for Black women based at Brown, but also open to other area colleges—Bryant University, Johnson & Wales University, Rhode Island College, Rhode Island School of Design, and the University of Rhode Island—since none of the them had enough Black women students to sustain separate chapters. In 1974, Sanford-Harris, Boddie-Rice, Cade, and seven other schoolmates made Brown history by becoming Lambda Iota’s first pledges.

“The focus of our entire pledging process was creating a collective community that would be of interest to other young women and carry the legacy forward.”

Action first, parties later

Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc. was founded in 1913 by 22 women attending Howard University in Washington, D.C. It is the fifth of nine historically African American Greek letter organizations, referred to as the Divine Nine, that formed during the 20th century with the goal of racial uplift. Delta’s founders were originally members of Alpha Kappa Alpha, the nation’s first Black sorority.

But when differences about the group’s focus arose—social activities versus social activism and public service—some women left and established a new sorority with the mission of being politically engaged. In March of 1913, just two months after its formation, Delta Sigma Theta’s first public act was marching in the Washington Women’s Suffrage Parade despite the white organizers’ reluctance to allow Black women to participate. They were the only African American women’s organization to march.

Over time, Delta Sigma Theta’s mission of service has evolved to focus specifically on education, health, economic development, global awareness, and political participation. In 2003, they became one of three African American women’s organizations to acquire NGO (non-governmental organization) special consultative status with the United Nations, which allows them to have a say in the implementation of international agreements in their areas of focus.

“I really liked that the founders of Delta Sigma Theta were socially aware and committed to social action and public service,” Sanford-Harris says. “That fit me and my ideology about what Black women could and should do.”

The Deltas were not the first African American Greek organization at Brown. A Brown chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha, a Black fraternity, was chartered in 1921. And a chapter of Omega Psi Phi, another Black fraternity, had formed on College Hill just a few years before the Deltas. The frat’s impending arrival on campus had been met with skepticism among some Black students. “There was a kind of questioning that ran through our community,” remembers Sanford-Harris. “We were very politically involved and very aware and proud of our Blackness.” Given the Black consciousness movement of the day, with James Brown’s “Say it loud, I’m Black and I’m proud!” proclamation resonating with a lot of young African Americans, belonging to a Greek organization seemed to some like a bourgeois throwback. Additionally, Sanford-Harris says, “some of us wondered, is this going to divide us in some way?”

As it turned out, the fraternity did not have the divisive impact that some feared. “The good thing was there was no change beyond the fact that some of our guy friends had become members of that organization. That kind of reassured everybody, so when Nanette asked if we would be interested in becoming Deltas the question had already been answered.”

In the spring of 1974, the 10 pledges began what Boddie-Rice describes as a “brief but intense” initiation process. There was no hazing, wearing matching outfits, or walking around campus in a single-file line. “It was more important that we got to class, did our class work, and got to the library to study” to maintain good academic standing—a non-negotiable requirement for pledging, says Sanford-Harris. “The one [uniform] thing we had to do was carry around a red folder that had a label with our Greek letters. I still have mine.” The official colors of Delta Sigma Theta are crimson and cream.

In a little over a month’s time, after becoming well versed in the sorority’s history, mission, and purpose, the 10 young pledges crossed over and became Deltas.

Typically, pledges have no idea when they will be inducted—that moment is sprung on them by their big-sister sorors. But the tradition was sidestepped for Lambda Iota’s charter line. “Nanette and the women of the alumnae chapter knew that four of us were in the Black Chorus and had a tour coming up, so they told us the date of our initiation in advance because we had to make arrangements,” says Sanford-Harris.

Cade remembers the mad scramble that she and other charter-line choir members made to participate in both events. According to her, “We wanted to stay in Providence and join the choir at the next stop, but we were also the strongest voices.” So, they followed the choir bus to Yale by car, performed, drove back to campus early the next morning for the induction ceremony that afternoon, then returned to Yale by train to rejoin the tour. “We spent the entire drive to Providence reciting everything [about Delta Sigma Theta] we could think of so that we would be ready.”

Their induction ceremony was held at an alumna’s home. “We had to wear white dresses, but I didn’t really like dresses back then, so I had to borrow one from an alumna’s 12-year-old daughter,” recalls Sanford-Harris, whose small stature allowed for a perfect fit. During the ceremony they performed a chant and step routine to the tune of the hit O’Jays song “For the Love of Money” and claimed their place as Deltas. “I can still hear it in my head, and I think I even remember the step,” says Boddie-Rice, chuckling at the thought.

During the ceremony they performed a chant and step routine to the tune of the hit O’Jays song “For the Love of Money” and claimed their place as Deltas.

All three women say that becoming Deltas was a proud moment, but also a little bittersweet for some who were seniors and about to graduate. “I had mixed feelings—really happy yet a little disappointed,” Sanford-Harris recalls. “It wasn’t like we had very much time together to get involved in community service as a chapter; we just appreciated the fact that we now belonged to this wonderful sisterhood.”

But, as Boddie-Rice explains, Lambda Iota’s first line was foundational. “The focus of our entire pledging process was creating a collective community that would be of interest to other young women and carry the legacy forward.”

A leadership incubator

Dr. Wanda McCoy ’78 pledged Delta in 1976, just two years after the formation of the charter line. “I knew nothing of fraternities and sororities,” she says, but she quickly learned thanks to her good buddy and eventual line sister Sherry Mills ’78, who schooled her on Delta. “When I found out about its history, the amazing [founders], and what they accomplished in their lives at that time, I was impressed and thought, how wonderful to be connected to this amazing group of Black women.”

Joelle Murchison ’95, a 1993 Lambda Iota pledge who is now on Brown’s board of trustees, remembers perusing the pages of the celebrated 1989 photo-essay book I Dream a World: Portraits of Black Women Who Changed America by photographer Brian Lanker, and realizing that a good percentage of the women featured were Deltas. “I was blown away, quite frankly, because these women were some of the most impactful figures in the country.” Congresswomen Shirley Chisholm and Barbara Jordan; former Secretary of Labor Alexis Herman; activist and NAACP Chairman Emerita Myrlie Evers-Williams; former HUD secretary Patricia Roberts Harris; artist Elizabeth Catlett; actress Ruby Dee Davis; and longtime president of the National Council of Negro Women Dorothy I. Height are just some of the prominent women who happened to be Deltas.

“My high school English teacher and volleyball coach were both Deltas,” says Tuneen Chisolm ’84, who pledged in 1982, but it was Brown’s Lambda Iotas who inspired her to join. “More than anything else, I was impressed by the tangible commitment to service that I saw from some of the Deltas I knew on campus,” she says. There was Kendelle Argrett ’82, whom Chisolm describes as “a strong, selfless student advocate on issues that were beyond her own individual interests.” And Dr. Patty Davis ’81, another Lambda Iota member, was also influential. “One day I stopped to chat with Patty, who was standing at the bus stop on Thayer Street. It turned out she was headed off College Hill to do her community service. She explained where and what, but I don’t remember that clearly. What I do remember is that encounter made a lasting impression and made me identify strongly with Delta.”

Says Valerie Kennedy ’85, of the 1984 Lambda Iota line, “The women who were perceived as leaders on campus and just getting things done were Lambda Iotas. They were about the business of excellence and were involved in all aspects of campus life.” Murchison agrees. “Our reputation was absolutely one of leadership on campus,” she says, citing fellow sorors who led organizations like the Black pre-med and pre-law societies, or were peer and residential counselors. During her own time at Brown, Murchison served as cochair of the Black Student Union and had a radio show on WBRU. “We did everything and were very visible,” recalls Murchison. “There was an expectation that to be a member of Lambda Iota, you’re not a slacker. You are going to go above and beyond.”

Lambda Iota made their presence known on campus through a number of signature projects and programs. “During my years, we sold Deltagrams as a Valentine’s Day fundraiser,” says Chisolm. “Students could pay a dollar and pick a song for us to serenade someone. We’d deliver a card and red or white carnation, too.”

“We did everything and were very visible,” recalls Murchison. “There was an expectation that to be a member of Lambda Iota, you’re not a slacker. You are going to go above and beyond.”

The Wrath of Redness, a monthly Lambda Iota–published newsletter, was launched during Murchison’s years on College Hill. “It had articles on things going on in Providence, or some community service we’d been doing, a soror spotlight, and other relevant topics for the student community, and we would distribute it on campus.”

Sisters Can We Talk? is a popular and enduring program that was also created during that time. “It was intended to provide a space for Black women to come together and talk about a variety of different topics that interest or impact them,” says Murchison.

Lambda Iotas continued Delta Sigma Theta’s mission of service. Sometimes they initiated their own projects, such as organizing a winter coat drive, a GED tutoring program, or a reading program for school children in underserved areas. Sometimes they supported existing organizations that were in step with causes they cared about.

“We partnered with Big Brothers Big Sisters for mentoring and tutoring,” Kennedy says, as well as organized a gift drive and Christmas party for the children they worked with.

The tradition of service has carried forward to more recent lines. Lambda Iota 2016 pledge Taylor Michael ’17, whose mother is Dr. Wanda McCoy ’78, joined with her soror contemporaries for the American Lung Association’s Fight for Air Climb to raise money and awareness to support healthy lungs and clean air. The fundraiser was at a Providence hotel that had “a crazy number of stairs, and we had to climb from the mezzanine floor all the way to the top.”

Pledging gets intense

Unlike the Lambda Iota charter line, subsequent lines’ initiation period became longer—six to eight weeks—and pledges endured the typical activities associated with joining a sorority. McCoy says what she remembers most was constantly trying to complete a multitude of tasks assigned by big-sister sorors. “What got me through was the bond and the friendship that I had [with my line sisters]. We boosted each other up.”

“We dressed in red and white the entire time and had two matching hats that we’d alternate wearing,” recalls Chisolm. “We walked in a height-order line whenever two or more of us were together, and being the tallest I was the tail, except for when we reversed the order.” All of this, she says, was done in the name of unity-building. “After walking in group step for nearly two months, you can’t help but learn to work together and move as a unit.”

“Pledging,” says Kennedy, “was just what I thought it would be—demanding and no-nonsense, with some ridiculous shenanigans.” Like the time big sisters instructed her line to collect pins from frat men they did not know. “We were chasing them down saying, ‘We need your pins, but we’ll give them back to you!’”

Michael credits Lambda Iota’s citywide status with getting her outside of the “Brown bubble.” She comments, “I think that being on an Ivy League campus, you kind of get sucked into thinking only about your experiences. Being able to think about college experiences other than mine was definitely humbling about being Delta.”

“We are certainly a diverse group,” says McCoy, who in retrospect views it as an advantage that enhanced her college experience. “It opens up your awareness and I think just makes you a better person when you are able to see things from different perspectives.”

Says Chisolm, “I’m proud of the breadth of our collective accomplishments. There are Lambda Iota–made Deltas representing in education, law and justice, STEM, medicine, publishing, activism, business, art, entertainment, and various other careers at all levels.” Another source of pride for her is the way Lambda Iota alumnae continue to connect with each other in large numbers at regional and national conventions and enjoy networking and bonding with sorors who pledged years or even decades before or after each other.

All of that sisterhood and camaraderie culminated at a reunion during the Brown Black Alumni Reunion (BAR) weekend in the fall of 2018. “We celebrated [our fiftieth] a little bit early to take advantage of the Brown BAR attendance,” explains Chisolm, who chaired the planning committee.

The event drew more than 100 sorors from across the nation, reflecting the four decades of Lambda Iota’s existence. Four women from the original charter line, including Sanford-Harris, attended while others sent written reflections and greetings to be shared. “It was inspiring to hear them speak about how Delta impacted their college experience and life,” says Chisolm.

They got to catch up with each other amidst workshops and panel discussions and meet with current Brown sorors to hear about what has and hasn’t changed. Sanford-Harris was happy to finally meet face-to-face with sisters she was acquainted with only through the Lambda Iota Facebook page. “It was nice to be together and reminisce about Brown, how it’s changed over the years, and how Lambda Iota has grown.”

The sisters managed to collect and donate 200 books to two area elementary schools as a community service project and held a reclamation ceremony to encourage inactive sorors to become active again.

A pinnacle moment occurred on Saturday afternoon when a procession of Lambda Iotas representing every line marched onto the Main Green dressed in crimson and cream and singing Delta songs as bystanders cheered.

“It was wonderful,” says McCoy, “because we got to show our presence in much bigger numbers than the campus is used to seeing. I think everyone was pleasantly surprised and happy to see that all these folks have this experience together, this relationship, and are part of this organization.”

“I wanted it to be as dramatic as possible,” says Kennedy, who organized the spectacle. “We really wanted to inspire other Black women on campus to feel a sense of ownership. That epitomized Black girl magic for sure!”

Like many Black Greek organizations on predominantly white college campuses, Lambda Iota has experienced some challenges in sustaining itself over the years. Some years it dwindled to only a few members and there were times the chapter was inactive altogether. Part of the struggle, says Sanford-Harris, is that over time the other colleges were not always keen on being part of a citywide chapter since it wasn’t an organization that they controlled. Also, she says, “there are so many other organizations on campus nowadays that may take up student time, maybe pledging Delta or any of the other sororities is not a priority.” Yet Lambda Iota has been resilient. Despite the challenges the pandemic has posed for all student organizations, nine pledges joined Lambda Iota this fall, boding well for the chapter’s future.

Kennedy, whose mother is a Delta, was eager to pledge the moment she stepped onto campus. “Brown wouldn’t be what it was for me without being in a sorority,” she says. “If you are talking about the historical narrative of Brown, and the arc of student life, you really have to talk about Lambda Iota and how it became this hub for Black women on campus to get a sense of terra firma that they may not have had without it.”

Julia Chance is a writer, visual art communicator, and author of the photo-essay book Sisterfriends: Portraits of Sisterly Love.