Must-See TV

A new book shows how 1970s shows like Sesame Street shaped a generation of kids.

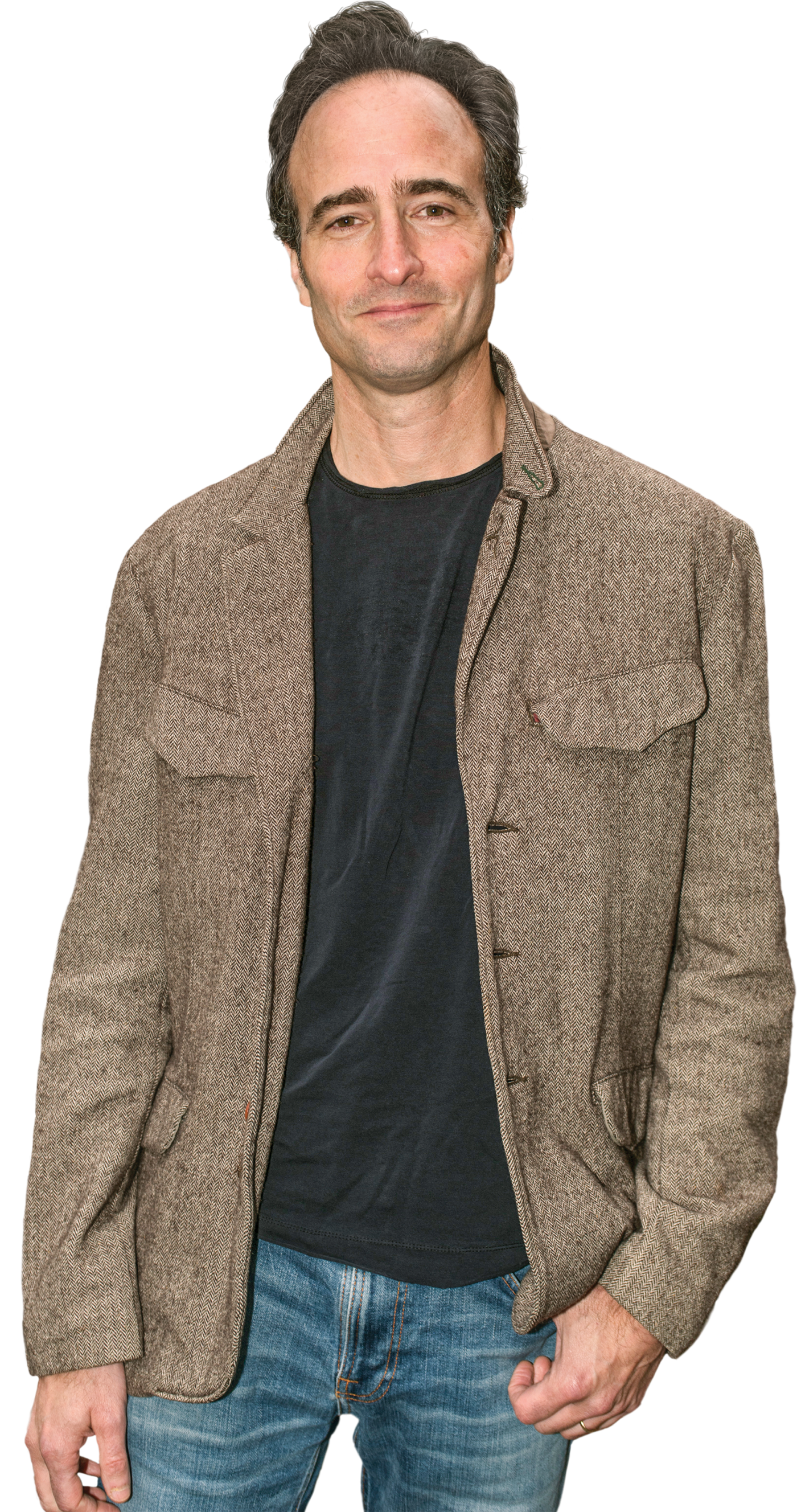

“I don’t want this to be just for Gen X readers,” says longtime writer and editor David Kamp ’89 of his new book Sunny Days: The Children’s Television Revolution That Changed America (Simon & Schuster, $27.50), published in May. Fair enough, but anyone who was in their single digits in the 1970s will probably experience a flood of sense-memory when they dive into this detailed, juicy account of the creation of Sesame Street, Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, The Electric Company, Schoolhouse Rock! and the other educational TV fare of that period—all of it created by progressive idealists betting that the “idiot box” could be used not only to entertain kids but also to improve their reading, math, and social skills.

What followed was a wildly creative and idealistic Great Society experiment, generously funded by the government and aimed especially at poor kids of color, on a scale unlike anything that had been attempted before—or since, Kamp says. “The federal government definitely would not get into the TV programming business today,” he says. It largely succeeded, he writes; studies of children before and after watching Sesame Street showed marked improvements in their learning skills.

Kamp, a longtime GQ and Vanity Fair contributor who also recently wrote lyrics for the forthcoming John Leguizamo comic musical Kiss My Aztec!, says that he initially wanted to write an account of the entire American seventies. “But the subject was too huge,” he says, “so I asked myself what components of that time spoke to me personally—and I couldn’t get out of my mind this cluster of TV shows that affected me and my generation in such a profound way.”

The challenge, he says, was going beyond feel-good nostalgia. Aided by copious interviews and archives, he’s written a serious but page-turning study of how people like Fred Rogers and Sesame Street creator Joan Ganz Cooney married the progressive, do-gooder ideals of the era with the zany hipster talents of folks like the late puppeteer Jim Henson. The result was skits and segments that both educated and mesmerized children while delighting adults with their lightly psychedelic funkiness and slyly satirical wit.

From the surprisingly fraught introduction of Roosevelt Franklin, Sesame Street’s first Black-identified Muppet (even though he was purple) to the now-famous cameos of luminaries like Morgan Freeman and Joan Rivers, from the actors who made up the beloved core casts to the fate of these shows as the idealism of the period gave way to the conservatism of the eighties, the book tells multiple narratives—reminding us that the issues of race and gender that animate us today were alive and well then, albeit on a somewhat simpler level.

“I’m hoping that people younger than I will read it,” says Kamp, “and see a model of how principled people can work really hard to make something good happen—and make it fun.”