In 1961, when Arlene Gorton ’52 returned to Brown as professor and head of physical education, women’s competitive athletics at Pembroke consisted of seven teams coached by gym teachers. Facilities included a small gymnasium, two tennis courts, and one outdoor field. There were no funds for team buses to away games in her annual budget of $2,000—money that was allocated not by the athletics department but from student activities fees.

Pembroke wasn’t alone. Nationally, women athletes were little more than an afterthought or a novelty. Only one in 27 women played sports in college. (Today that number is two in every five.) Change began in earnest in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when the women’s liberation movement exploded traditional notions of feminine behavior and potential. On College Hill, the 1971 Brown-Pembroke merger and the passage of Title IX of the 1972 U.S. Education Amendments helped launch a remarkable growth in women’s intercollegiate sports. By 1973, the women’s teams began to share in the overall University athletic budget, and by the end of the 1970s, there were 15 women’s varsity sports.

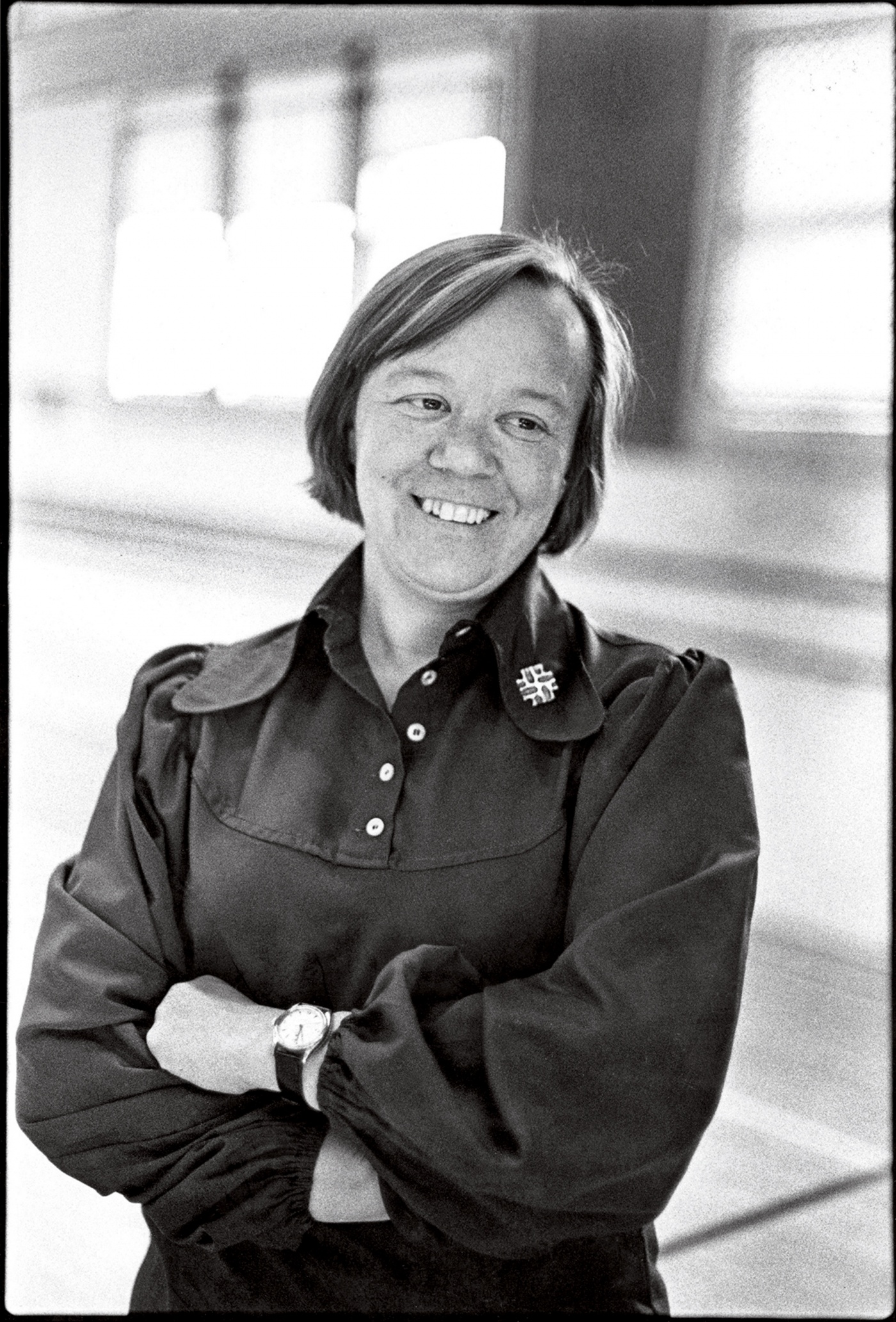

Gorton, who died on January 3 at age 88, was the chief architect and catalyst of today’s robust varsity women’s programs. Throughout her 37-year career at Brown she pushed to ensure women athletes received—in the words of Title IX—“a fair balance of competitive opportunities and equality in services and facilities.” Her blunt advocacy for more women’s funding and recognition didn’t always win friends among administrators and coaches who feared that men’s varsity resources would be diminished. Nevertheless, Gorton persevered. “I’m not shy,” she said. “I stirred the pot and raised questions. I never wanted to hurt the men—I just wanted the women to have a fair shake.” (Quotes from Gorton are drawn from a number of newspaper, magazine, and web articles, as well as oral history interviews.)

“Arlene was ahead of her time,” says Carolan Norris, senior associate director of athletics and a former Brown field hockey coach. “What she was trying to do for women athletes beginning more than 50 years ago is the norm now.”

Gorton learned early that being a girl meant she wouldn’t be able to pursue all of her athletic dreams. Growing up in Rhode Island, she wanted to play for the Red Sox alongside her idol, Ted Williams. “My dad told me I couldn’t play because I was female,” she said. “I got really irritated.” Later, at Pembroke, Gorton was captain of the softball team and the top singles player for the badminton team. “We probably had about eight or ten contests per season,” she recalled, with the level of play a far cry from the intensity of women’s competition today. “The women physical educators at that time didn’t like the term ‘varsity sport,’” Gorton recalled, “so they called the teams ‘clubs.’”

Upon graduating with an English degree, Gorton did two years of graduate work at the University of North Carolina and then taught for seven years at Connecticut College before moving into her office in Pembroke’s Sayles Gymnasium. There, she maintained an open-door policy for coaches and students. “Whenever anyone walked into her office,” says Norris, “she stopped everything. She was a tremendous listener.”

In the early 60s, in what proved to be a harbinger of changes in women’s sports, some Pembroke students knocked on Gorton’s office door to ask about starting a women’s ice hockey team. Gorton agreed, while cautioning that resources would be scant. The women skaters wore hand-me-down Peewee jerseys and helmets, and shin pads strapped over blue jeans. They could only get ice time for practices late at night. With no travel budget and no U.S. college competition at the time, they sold chocolate bars to charter buses for away games in Montreal. The ice hockey program went on to great success in the 1980s and 1990s, but Gorton initially got some flak for greenlighting a women’s team. “I got letters,” she recalled, “saying, ‘They’ll get hit with the puck, they’ll be disfigured! They’ll injure their reproductive organs.’”

To this day Gorton is counted as a hero by several generations of Brown athletes. “She was such a support for those of us at Pembroke who were involved with athletics,” says Nancy Parr ’68. “The sixties were an era when women were not generally encouraged to take sports seriously. Arlene Gorton created an atmosphere where I could feel okay wanting to push myself.” A post on the Women’s Soccer Friends Facebook page notes, “She is the reason we are a varsity soccer team.” Brown sports archivist Peter Mackie ’59, who has proposed that the University name an athletic field for Gorton, describes her leadership as “visionary and transformational.”

Over time Gorton was named assistant and then associate director of athletics at Brown, expanding her role beyond women’s sports. Her status as professor of physical education was important to her: “I would not have returned to Brown had I not been given a faculty appointment—not because I’m on an ego trip, but because I believe it reflected the commitment I expected the University to make to sport in education.” Her status as a faculty member also broadened her role on campus to faculty affairs in general, as well as fighting for women’s equity. She chaired the Faculty Policy Group and played a key role in the Louise Lamphere tenure discrimination suit against Brown in the 1970s.

For her work on behalf of women college athletes and, more generally, women in higher education, Gorton won numerous national and regional awards, and in 1998 she was inducted into the Brown Athletic Hall of Fame. Annually, Brown presents the Arlene Gorton Cup to a female varsity athlete who displays the ideals of sportsmanship.

Gorton retired from Brown in 1998, giving her more time to follow the Red Sox and enjoy her cottage retreat on Prudence Island in Narragansett Bay. “Arlene had a love for Rhode Island and her Prudence property,” says Norris. “It was where her balance came from, where she regrouped and re-energized. Her nephew put cinderblocks under her bed so she could look out the window over the bay. She loved to entertain coaches and friends there, and we would all come back refreshed. With Arlene, it was nonstop giving.”

In the end, as Gorton looked back on her long career, she wryly admitted to one regret. “I still think I should’ve been able to play for the Red Sox.”