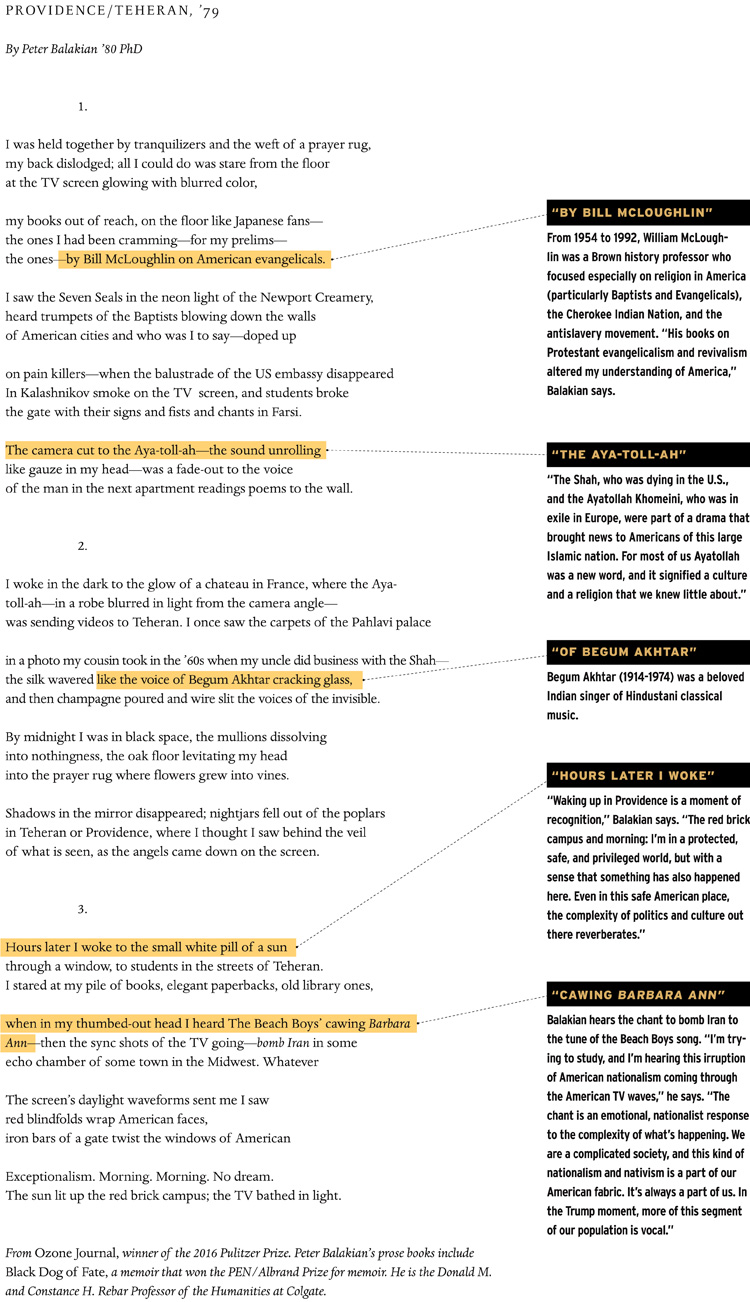

With Iran so prevalent in our news and politics this past year, it may be useful to go back almost 40 years to November 4, 1979, when Islamic students in Teheran stormed the U.S embassy and took 52 American hostages who would be prisoners there for 444 days. After the humiliations of the Vietnam War, the hostage crisis triggered, among other things, an upsurge in patriotism in the United States and has influenced our relations with Muslim countries ever since. On that same November day, Peter Balakian ’80 PhD, who was in the final stages of earning a doctorate in American civilization, lay on his back on the floor of his Providence apartment on the corner of Medway Street and Wayland Square, watching events unfold on a small Sony television. Balakian had injured his back two days earlier while defrosting his refrigerator. His girlfriend—later his wife—brought him painkillers, which only partially dulled his agony, and made the events of that day—preparing for preliminary exams, trying to understand the Teheran events through the lens of a gritty TV screen, listening to neighbors, managing excruciating pain—seem like a surreal, waking dream.

It lasted a long time. “Poems emerge from strange intersections of circumstances, images, events, inventions, and feelings,” Balakian says. “A poem isn’t a memoir, but it can be rooted in a time and place and event.” Thirty-five years after that day in November, while he was working on the poems that became Ozone Journal—the only book by a Brown alum to earn a Pulitzer Prize for poetry—Balakian returned to the experience of that day to write “Providence/Teheran, ’79.” Many books by scholars, diplomats, White House officials—even former hostages—have been written about the U.S.-Iran relationship since 1979, but it remains complex and difficult to fathom. What possible light could a poem shed on the subject?

“I carried in my head for a long time the powerful impact of the hostage crisis on American culture,” Balakian recalls. “In writing this poem, I wanted to bring the reader into this explosive experience. I wanted readers to realize: ‘Wow, a poem can take me to that moment.’”

The TV screen became “both a conduit to what is happening and a sort of veil to look behind, where deeper knowledge exists, in the sense that Hawthorne and Melville meant it. In the poem I am experiencing a collision of cultures in a profound way, critiquing the complexity of my own culture’s failures to read deeply the texts of other cultures. I’m not trying to tell the reader what to think; I’m talking about my own experience. But I hope the reader will recognize the need to make an inquest, to go behind the veil.”