I still hadn’t fully processed our move to Venice, California, when I came face to face with the grizzled guy on our block who rides around on the yellow scooter. “You grow up here?” he asked.

In some ways, we were adjusting quickly to our new California life. I started wearing nothing but shorts and a T-shirt the first day we arrived. Kelly bought a surfboard. And on a recent night, my four-year-old daughter, Loretta, had gone to sleep, her hair still wet from the beach, with a halo of sand circling her body. “Let’s stay here forever,” she’d said.

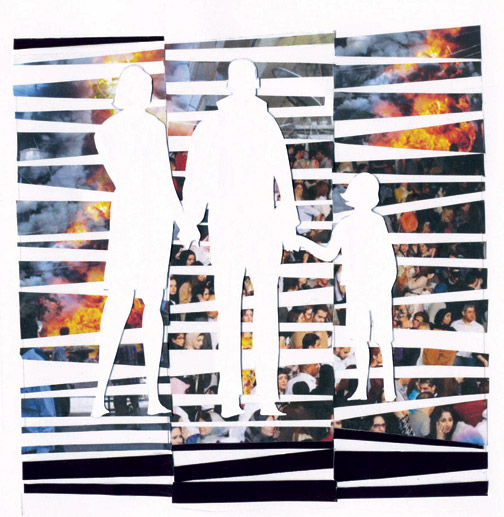

But during ten years of marriage and nearly fifteen together, Kelly and I have moved roughly every eighteen months, always in search of the next big thrill. Our move to Los Angeles had perhaps signaled an end to that frantic search. Could we really settle down?

It’s not like we hadn’t ever nested. In Saudi Arabia, we’d tried and failed to find peanut butter and decent sausage, but once we discovered a place to jog at night and made genuine friends among the Saudis, the oddness of the place had fallen away. In Istanbul, I’d had trouble cottoning to the new-money glamour of a city and country that, at heart, still felt intimately tied to the brutality of military rule and the occasional pogrom. Then I started meeting all the crazy countercultural artists.

Lebanon had its own charms. Thanks to French influence, the wine was great, the music loud, and if you squinted, you could pretend you were in Europe. Trying to class up my act, I trimmed my beard, wore a sport coat, and polished my shoes more than once. Yet all the while there was the thumping undercurrent of violence and war.

In California, on the other hand, everything felt too easy, too nice, and it was this absence of struggle that made its charms alone feel insufficient.

“Well, if you’re not from here,” the scooter guy said, “do you know where to eat?”

I thought about it. I did not, in fact, know where to find a good meal in Southern California.

“Take breakfast at Maxwell’s,” he said. “I go there every day.”

With a wave, he turned to leave, and with the sun dipping into the ocean, and me at least marginally more informed about my new town, I realized one small thing. We might not stay long in Venice, we might not find stimulation at all equal to the life we’d known in the Middle East, and we might not ever really enjoy a quieter life. But the next time we hosted visitors, I’d know where to take them for breakfast.

Nathan Deuel is the author of the essay collection Friday Was the Bomb.

Illustration by Chris Sharp