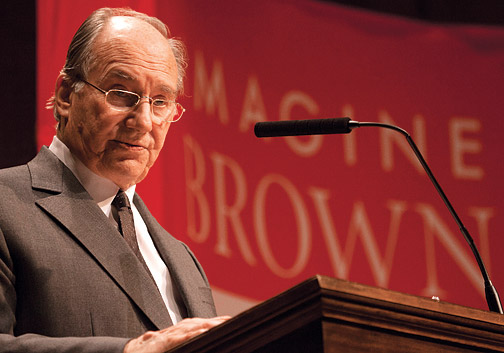

Over the past decade “thirty-seven nations around the world have been writing or rewriting their constitutions, with another twelve recently embarking on this path,” the Aga Khan observed when he visited Brown March 10 for a Stephen A. Ogden ’60 Memorial Lecture. “This means that nearly 25 percent of the member countries of the United Nations have been rethinking these central governance concerns. And nearly half of these forty-nine countries have majority Muslim populations.”

Educated in Islamic schools and then at Harvard, the Aga Khan assumed his position in 1957, and in 1981 he founded the Aga Khan Development Network, a constellation of nonprofits fighting poverty in thirty nations across Asia, Africa, Europe, and North America. He received an honorary degree from Brown in 1996 and delivered the Baccalaureate address that year. In his Ogden Lecture the Aga Khan pointed to his son Rahim ’95 watching intently from the audience and congratulated Brown for “completing its first quarter of a millennium.”

In his lecture, the Aga Kahn warned of the dangers of factionalism. Although inclusiveness and cosmopolitanism were central to Islamic culture centuries ago, he said warring factions—especially the conflict between Sunni and Shia Muslims—now loom large.

“In places like Pakistan and Malaysia, Iraq and Syria, Lebanon and Bahrain, Yemen and Somalia and Afghanistan, the Sunni-Shia conflict is becoming an absolute disaster,” the Aga Khan warned. “The harsh truth is that religious hostility and intolerance, between as well as within religions, is contributing to violent crises and political impasse all across the world.”

Technology might seem to offer hope, but “greater connectivity does not necessarily mean greater connection,” he said. Instead, he argued, the “incalculable multiplication of information” we receive via smart phones and laptops “can also mean more error, more exaggeration, more misinformation, more disinformation, more propaganda.” He warned that technology’s centrifugal forces can actually widen the “knowledge gap” within and between civilizations, broadening a perilous “empathy gap.”

What is needed, the Aga Khan said, is a renewed commitment to pluralism and civil society—to a world in which difference “can become an opportunity, not a threat, a blessing rather than a burden.”

Join the BAM conversation on Facebook and Twitter.