Then the host held up his hand and switched to his radio voice.

"Good Morning, Bay Area," he said. "David Shenk is with us this morning. He's written a fascinating new book which basically says that the Internet is a giant hoax."

I thought I was going to swallow my tongue.

Perhaps this is what makes so many academics averse to communicating with the general public. After all, you are bound to be misunderstood. If you spend your life in a world of books and ideas, there's nothing worse than sitting in a chilly, windowless room staring at your own face on a TV monitor while someone with a waxed face and a very crisp shirt sums up your life's work with the line, "Thank you, professor, for showing us how debt markets spur marital infidelity."

The other option is to have someone like me serve as the middleman for your ideas. But academics generally don't cotton to that either. After decades of being rewarded for going deeper and deeper into subtleties, why would scholars want their work dumbed down? My own experience in trying to do this in front of large academic audiences went well—if you compare it to periodontal work.

But we simply need this to happen. More than ever, we need public intellectuals willing to bridge different worlds. As complexity threatens to overwhelm us, an increasingly distracted public needs to understand how genes really work, how markets can be both encouraged and reined in, how history teaches us about politics. We need to understand at least a little about how our tiny computers work so we don't become alienated from the tools that regulate our lives.

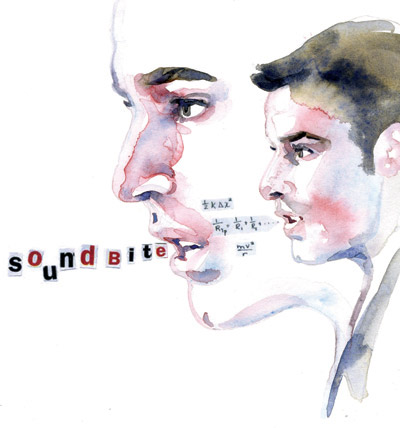

Whether we like it or not, we need more sound bites—and more creative metaphors and clever narratives. Intellectuals should spend as much time tuning their work for public consumption as they do composing for their own kind. This might put idea-middlemen like me out of business, but it would help make the world safer, more prosperous, and less prone to demagoguery.

David Shenk is the author of five nonfiction books and is a correspondent for TheAtlantic.com. His next book, The Genius in All of Us, will be published in March.