Satchel: The Life and Times of an American Legend, by Larry Tye (Random House).

Don't look back, Satchel. The biographers are gaining on you.

Not to worry, though. Journalist Larry Tye's exhaustively researched, readable, and unfailingly interesting biography of Leroy "Satchel" Paige shows that if ever a life lived up to its legend, his did. The baseball pitcher was, in Tye's words, "a star almost from day one," despite "playing in an obscure universe," including the Negro Leagues and barnstorming circuits to which African American players were relegated before World War II. And although Tye overestimates the role Paige had in ending segregation through his insistence on guaranteed accommodations in Jim Crow America and on playing exhibitions with white stars (including Dizzy Dean and Bob Feller), he does have a point.

Tye bases his book on the extensive literature about African American baseball that has emerged since the 1970 publication of Robert Peterson's classic, Only the Ball Was White, and on interviews with just about everyone who came into contact with Paige, including his family. Along the way Tye comes at least close to resolving all sorts of issues—from Paige's exact age, to how he got his nickname, to how many games he actually pitched. In the portrait that emerges, Paige grows in stature as an athlete and as a brilliantly self-promoting black entrepreneur in a difficult, sometimes dangerous world.

Born in 1906, one of twelve children, Paige had a hardscrabble childhood in Mobile, Alabama, and emerged from the Alabama Reform School for Juvenile Negro Law-Breakers in 1923 with extraordinary baseball skills and an appetite for life. Tye vividly portrays Paige's itinerant career: "He was the nation's ringer, generating more offers than anyone and picking up as much as $500 for as few as three innings....Promoters knew he could fill the stands as well as mow down batters, so they booked him despite knowing he might not show."

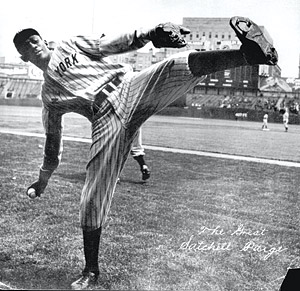

An overpowering pitcher with a bewildering variety of precisely placed deliveries, Paige was also a showman who knew how to work a crowd. At 6-foot-3-inches and 140 pounds, he proceeded with elaborate deliberateness to the mound, cutting an intentionally disarming and comic figure. But when the game began, Tye writes, "Satchel got serious, kicking back his foot, twisting his leg like a pretzel, whipping his arm around, and sending the ball plateward like incoming artillery." Sometimes, even against good teams, he told his outfielders to sit down and then struck out the opposing lineup.

He played all around the United States, Mexico, and the Caribbean, finally settling with the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro League. The money rolled in, then right back out—for shoes, suits, and high living. On the road with the Monarchs, "he kept an electric stove in his hotel room to pan fry (in expensive sherry) the catfish he caught or bought."

After decades on the margins, Paige was upset when Branch Rickey chose the younger, less unpredictable Jackie Robinson to desegregate the Majors. But Bill Veeck brought Paige to the Cleveland Indians to help win the 1948 pennant, and he received belated recognition when he was named to the Hall of Fame in 1971.

Always the humorous self-promoter, Paige called one of his semi-reliable autobiographies Maybe I'll Pitch Forever. Thanks to this lively, three-dimensional portrait, in a way he's doing just that.

Luther Spoehr is a senior lecturer in Brown's education department.