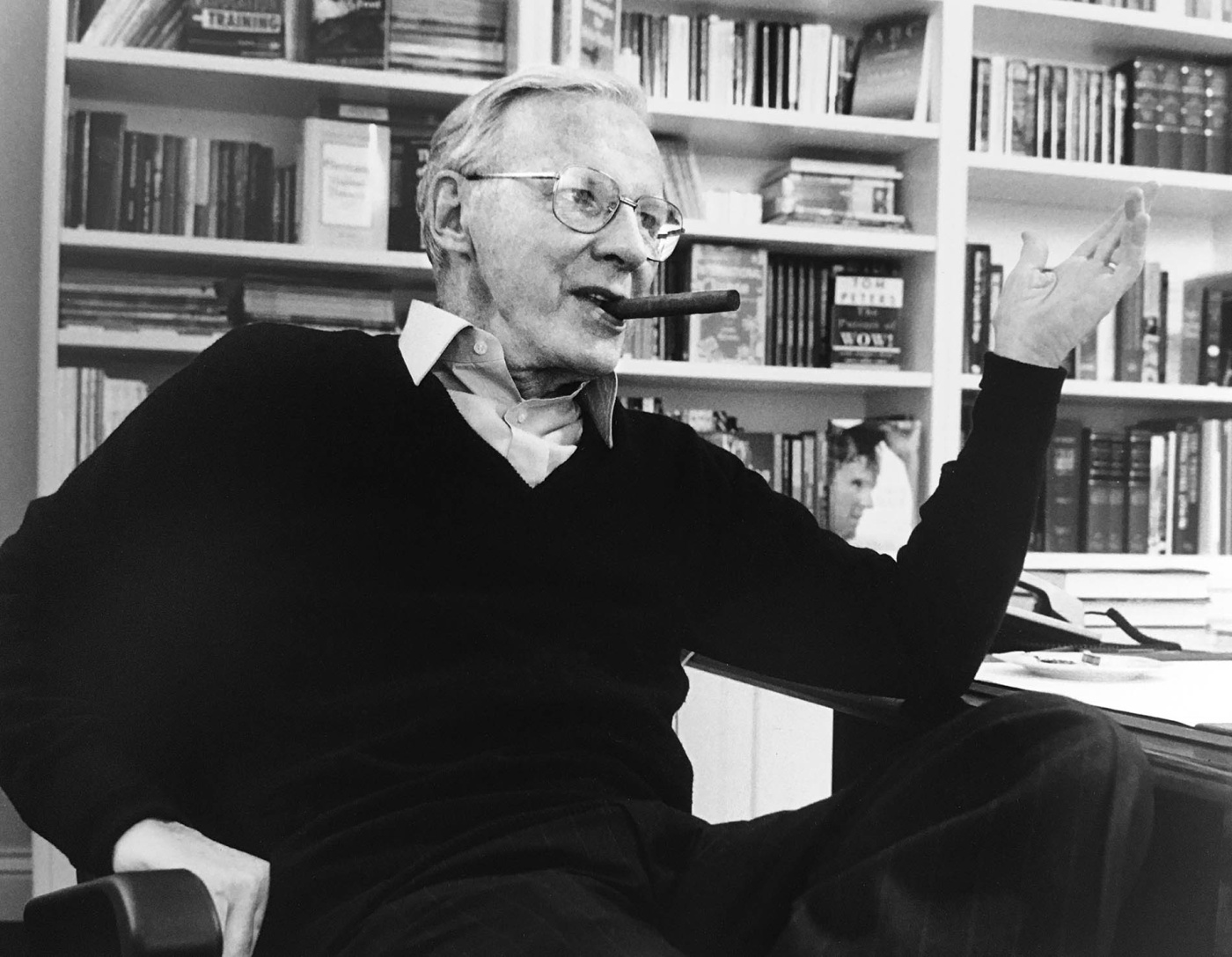

Sally Richardson, a longtimer with the venerable publishing house St. Martin’s Press, tells a tale of how Tom McCormack ’54, the house’s legendary chief executive from 1970 until his retirement in the late 1990s, turned the place around. When McCormack took over, Richardson recalls,St. Martin’s mainly published academic and children’s books. McCormack wanted it to publish adult trade books. He began asking agents for manuscripts, she says, but New York agents were all loyal to trade titans like Charles Scribner or Bennett Cerf. So McCormack and his wife, Sandra Danenberg, a St. Martin’s editor, went to London. “But they were snobby too and didn’t appreciate what Tom was trying to do,” says Richardson. Finally, she says, McCormack, frustrated, said to one agent: “Is there nothing you can give us to read? We’ll read it overnight and make you an offer tomorrow.” Exasperated, the agent pulled down two small volumes by an author named James Herriot. They were about a rural British veterinarian in the 1930s. McCormack and Danenberg took them home, fell in love with them and, according to Richardson, said, “We’ve got a big winner here.” They were right. The book was 1972’s All Creatures Great and Small and it became an early blockbuster for St. Martin’s trade list, which would also go on to include 1978’s The Far Pavilions and 1988’s The Silence of the Lambs.

McCormack died on June 15 at age 92 at his home in Manhattan, survived by his son Daniel McCormack ’90 and daughter Jessie McCormack ’95. (Danenberg died in 2013.) He is remembered as the man who shrewdly transformed the publishing company, in the words of a long-ago Publishers Weekly article, “from an insignificant trade house on the brink of bankruptcy to a quarter-billion-dollar powerhouse with one of the most extensive lists in the business.” According to his New York Times obituary, McCormack not only published more fiction than any other house, he also in the late 1980s started the first mass-market paperback line at a hardcover house since Penguin introduced Pocket Books in 1939. Publishers Weekly also once said of him that “he believed, against the publishing grain, in volume at all costs.” During his tenure, according to a statement St. Martin’s put out right after his death, he grew the house’s annual billing from $2.5 million to $250 million.

McCormack was born in 1932 in Boston as Michael Gerrard Griffin but was renamed by his adoptive parents. He attended Stamford High School in Connecticut, then graduated summa cum laude and with a 4.0 average from Brown, where he majored in philosophy. After serving in the Army, he was a Woodrow Wilson Fellow at Harvard. He then wrote for news radio until he joined the publishing house Doubleday in 1959, followed by gigs at Harper and Row and New American Library, where he published James D. Watson’s bestseller The Double Helix, about his role in the discovery of DNA’s structure.

Once he arrived at St. Martin’s, he was not only chief executive but editorial director. The Times obit said that he had “a rare fusion of marketing savvy, which enabled him to buy future best-sellers, and editorial scrupulousness, which led him to make good books even better.” Richardson echoes that. “He was as smart as they came and you could put him up against Tolstoy, but he wanted to make money and grow the house by publishing as much as he could,” she says. “He didn’t care about the business side but he learned enough to know what you needed to know, which included hiring keen business people.” Although he would oblige authors and others the once-legendary, alcohol-heavy “publishing lunch,” says Richardson, he was known for eating a tuna sandwich at his desk most days. That illustrated his down-to-earth approachability. “He was the first person in his adopted family who went to college and had no time for phonies,” she says. “If you were going off on a wrong tangent or acting like an ass, he’d tell you that you’d lost sight of the goal—but he did it in a constructive way so that you grew and learned from it.” In the St. Martin’s statement, editor in chief George Witte, who worked with McCormack for years, called him “a meticulous, perceptive editor and a canny businessman...But more than anything, he was a teacher, and the time he gave to young editors was extraordinary. An unusual number of the assistants at St. Martin’s have gone on to significant executive and editorial careers—a lasting legacy of Tom’s mentoring.”

McCormack helped negotiate St. Martin’s sale to Holtzbrinck Publishing Group of Germany before he retired, after which he wrote for a year a Publishers Weekly column about the book biz called “The Cheerful Skeptic.” There, he was often wittily acerbic. “The nearest thing to a crisis in publishing is guys like [author] Ken Auletta writing about ‘the crisis’ in publishing,” he wrote in 1997. “Reading his piece in the New Yorker [about publishing’s woes] is better for the cardiovascular system than a hard jog in the park. Picture a man my age doing a breakdance—of frustration. I counted 16 passages...that made me want to call 911.”Post-retirement, he also wrote a nonfiction guide called The Fiction Editor, the Novel, and the Novelist, and two plays, American Roulette and Endpapers (about power struggles at a publishing company), the latter of which was produced off-Broadway. He was such a theater lover, in fact, that he donated money to Brown to build the McCormack Family Theater. “He was very unflappable and the least neurotic person I've ever met,” remembers his daughter, Jessie, a writer and director in Los Angeles. “There were always piles of manuscripts all over the house, but he always had time for us kids.” She says he was often the only parent at the park who actually would play along with them, which made the other kids flock to him. And, she says, he had a delightful and goofy sense of humor. During his tenure, she says, St. Martin’s was in New York City’s iconic Flatiron Building, which is shaped like a wedge. Of confidential work business, she says, her dad would always say, “These conversations must stay inside these three walls.” She laughs while retelling this. “It’s such a dad joke,” she says.