A Challenge at the Outset

From the Archives

This article originally appeared in the Brown Alumni Monthly, Nov.–Dec. 1946.

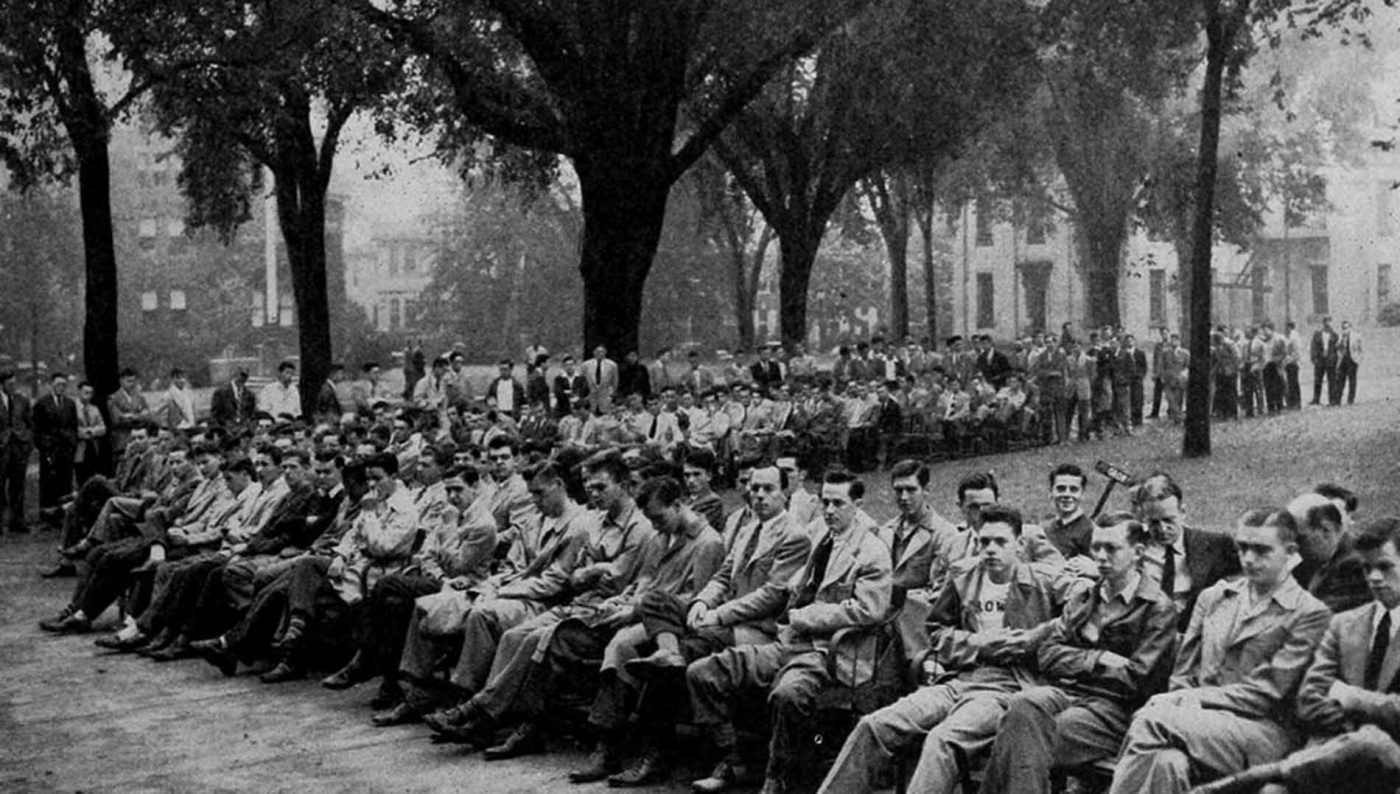

“The most extraordinary convocation in the history of Brown University,” the President called it. “It meets in the largest assembly space we have, yet the room does not accommodate even half the undergraduate men. The other halls which we have at present will not hold even a third of the student body of the College.” He was speaking from the platform of Sales Hall, and his voice was carried by public address to the Middle Campus where an outside audience listened in.

This inaugural crowding, the President said, was symptomatic of the situation at every step: "There have been not only more people to register this fall but more problems in registration than ever before. Backgrounds are more various, there are more special cases, more exceptions, more irregularities — and all those take time. Despite great exertion on the part of the builder and the architects, the new classroom building is not ready. Permanent housing is short; temporary housing is not completed. Among those of you who have been in the armed forces, the word 'snafu' will come readily to your lips.”

"But," Dr. Wriston pointed out, "there is something — indeed a great deal — on the other side of the ledger. The University could have sought its own convenience, closed the door, and refused further admissions when a comfortable maximum was reached. It did not do that because no one wanted to disappoint or delay students who were fully ready and fully capable if by any extraordinary effort such delay and disappointment could be prevented. Yet in the effort to disappoint no one, we shall in some measure disappoint you all. When you are tempted to be impatient, just remember you would be even more impatient if you had been denied admission in order to increase someone else's comfort so his patience would not be taxed."

CAREFULLY SCREENED

Another item appeared on the credit side of the ledger. The size of the student body was its least significant quality, for it was the best-qualified ever to enter Brown. Out of the entire 2600, no one needed to be dropped from College nor even to fail a single course. "In a group with as high an intellectual potential as you have, any failure will be due to lack of will, to want of application, or to carelessness — not to incapacity." A special obligation to work was implicit in this.

Another obligation lay in the field of public relations: "The relationship between the city and the campus is more critical than ever before," President Wriston said. "Long ago it was found to be sound policy to have students live on the campus rather than in town. Circumstances compel us to suspend that sound policy and to have many of you living not only in the town but among people who do not have you in their homes from choice but only from a sense of public service. They have displayed a hospitality which runs beyond all expectations. People who knew students only remotely and at a distance are going to know them intimately and at first hand. Inevitably this means that your conduct will be under observation more closely than at any time in the modern history of Brown University.

"You can do something to help the University, but it will require a special effort on your part. You can do even more to injure the University and that can be done not merely through malice, of which none would be guilty; it can result from failure to be thoughtful, by neglect of courtesies, by carelessness. We are engaged in a campaign to raise money for an extensive student housing project. Most of you cannot give money, but you can keep us from obtaining it by convincing people who are in contact with you that you are unworthy. On the other hand, you can help us to raise the money and build the modern housing in time for many of you to occupy it if you are responsible and spread good will. Our public relations, to put it in a nutshell, are in your hands.”

CAMPUS CITIZENSHIP

Citizenship, like charity, begins at home, the President said, in pointing to another extraordinary aspect of the situation: "Never before in the history of Brown University have its tone, its temper, and its general atmosphere been so fully under the control of the students. You are so many; few of you are acquainted with the traditions; many of the traditions are not adapted to the current circumstances. Therefore the problem of undergraduate leadership and of sound public opinion among the undergraduates is unique. There is a rare opportunity for the student body to develop a distinctive morale." The place where citizenship could best be displayed was right here on the campus, and the foundation for college morale must be an understanding sympathy between the students and the Faculty.

What had the educative process in college to offer? One should learn by every experience of life, and one learned by doing. ("Sometimes I am tempted to believe that the most rapid period of learning is during the first two or three years of life, when, without the benefit of formal schooling, enormous vistas of communication and understanding are opened up. . . . I know no way to learn politics except by participation; that is why I do not become upset by college politics, which are often more subtle and more ruthless than the politics of the world outside.")

“But college has one distinctive method of learning not duplicated in anything like the same degree elsewhere," Dr. Wriston continued. "That is learning from books. . . . There is no conflict between learning by doing and learning from books. They are both valid, they are both essential. . . . You do not come here barren of education: A large number come directly from secondary schools scattered far and wide over this nation. Others among you could write a condensed biography similar to the soldier who said he was born in Brooklyn and grew up on Okinawa. You have a first hand knowledge of the world's geography and intimate knowledge of other cultures, so-called. Many of you have been learning by doing at a furious rate. Some have been learning by boredom: One ex-G.I., describing his present dull job, said that his employers had made it as stupid as they could, but they could not make it as stupid as his previous experience, for in the service he had been bored by experts."

The President did not ask them to stop learning by doing, but this was the time and the place to learn from books: "This is the golden opportunity to redress the balance which over-emphasis from action during the war has upset. Now you should establish habits of living with books and learning from books, of acquiring knowledge from books that will remain with you forever, as a compensatory factor in the rush of the world. . . . Whatever the mind of man has conceived, whatever problems he has solved, whatever his achievements, physical or spiritual — all are available to you. You will do well to make your college years a season of saturation in the thoughts and triumphs of your predecessors. For upon those foundations our daily turmoil is superimposed. Only by knowing the past can present activities be seen to have had causes. Only by knowing the relation of cause to effect can you grasp and finally master the problem of our civilization.”