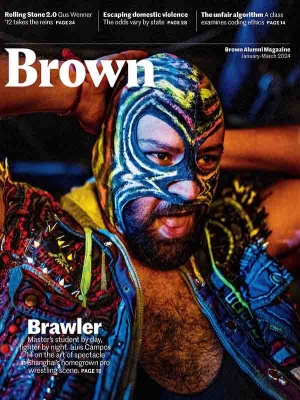

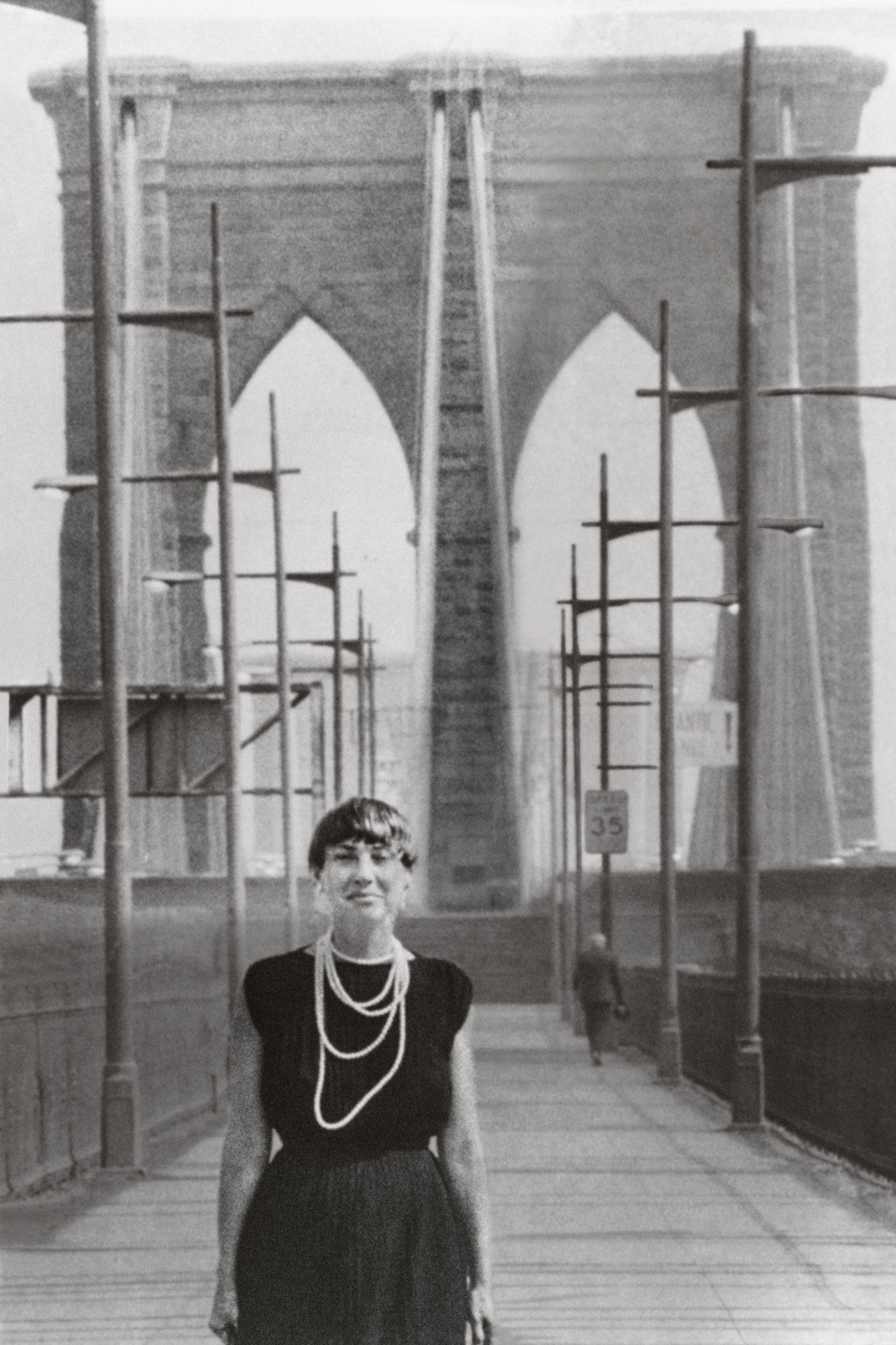

Preservation Pioneer

Beverly Moss Spatt ’45 helped save countless NYC landmarks

The person most popularly associated with saving New York City’s Grand Central Terminal in the 1970s is Jacqueline Onassis, who indeed, via the Municipal Arts Society, played a major role in the successful public campaign to preserve the Beaux-Arts masterpiece.

But Onassis’s government-side counterpart was Beverly Moss Spatt ’45, a native Brooklyner who from 1974 to 1978 was chair of the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC). Technically, it was an appeals court that forbade the tear-down—a ruling confirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1978—but Spatt, as the city’s popular face of preservation, made it her priority and called the appeals court’s ruling “the most important decision that the preservation movement has ever had.” The Supreme Court ruling, in particular, gave strong precedent to the idea that buildings or structures of historic significance could not be torn down or disfigured just because their owners were facing economic hardship.

With Moss Spatt at the helm, “the LPC fought all the way to the Supreme Court and won,” says James Sanders, an architect who worked under her at the LPC. “That not only saved Grand Central but firmly established that landmark preservation was a legitimate purpose of government.”

Moss Spatt died on Jul. 14 at age 99. As recently as 2015, she had not only joined a coalition that successfully blocked structural changes to the 1935 Frick Collection, she’d also voiced her concerns in a battle over the air rights for Pier 40 in the Village on Manhattan’s West Side.

That’s according to Andrew Berman, executive director of the advocacy group Village Preservation, who says Moss Spatt’s time as LPC chair “impacted our neighborhoods substantially.” Indeed, her four-year tenure oversaw the designation of more than 800 landmarks including, to quote her obituary in the New York Times, “mansions, Broadway theaters, apartment and commercial buildings, gems like the New York County Courthouse in Foley Square, historic districts on the Upper East Side, scenic spaces in Central Park and Verdi Square...and even the magnificent interiors of City Hall and the New York Public Library....”

“She was revolutionary,” says Sanders. “She’d gone to Pembroke and gotten her PhD at NYU in urban planning, but she wasn’t part of the insular landmarks world. She was an activist who was interested in the city as a whole and opened up the LPC, which had previously operated like a private club. She pushed back on the power of real estate developers.” She also promoted landmarking as “a powerful new way to protect one’s community, specifically with the rise of entire historic districts.” (Sanders acknowledged that, since the 1970s, landmarking has to some extent been used to block the creation of new housing—especially low-income and affordable.)

The daughter of a judge, Moss Spatt was on the City Planning Commission in the 1960s, where, according to her Times obit, “she got out and spoke to people in the neighborhoods, carried their fights to City Hall, and developed a low tolerance for back room deals.” She opposed the city’s massive 1969 “Master Plan” for its future. “She felt it was focused too much on economic growth and too little on working-class communities,” says Sanders. “She didn’t care what people thought of her,” he adds, and took that attitude “right up to the mayor.”

Perhaps because of that, Mayor John Lindsay didn’t reappoint her to the commission, which led to an uproar in which the Times, defending her, wrote, “She has been available to the public...people are convinced she cares.” She also taught at Barnard College and was a special assistant to Bishop Joseph Sullivan of Brooklyn. Mayor Ed Koch in 1978 did not reappoint her LPC chair, but she remained a member until 1982. She declined a preservation position in state government after that and became a private citizen.

According to her son, David Spatt, a professor at Johnson & Wales, she spent many years caring for her husband, Dr. Samuel Spatt, before his death of congestive heart failure in 2007.

“She was very determined and wasn’t afraid to stand up for what she believed,” he says, guessing that she derived her passion for preservation partly from seeing a working-class, largely non-white section of her own childhood neighborhood, Brooklyn Heights, get torn down in the 1930s to build Cadman Plaza. “The press loved her, especially when she did controversial things against the mayor.”

“She was short, energetic, and hyperactive—very New York,” says Sanders. “She was an uber, elevated version of the neighborhood lady who goes to all the hearings and lets the commissioners have a piece of her mind.”

In a long 2017 interview for Village Preservation, she said, “Of course, originally, the Landmarks Commission belonged to a small group of people, the Manhattan people, who were powerful, totally out of proportion to their numbers. That’s ’til I came in.” She added: “If you do good for the people, and you believe in something, people trust you.”

She is survived by her children, David, Robin, and Jonathan, and three grandchildren.