How to Read a Picture

A course applies seminal texts to classic LGBTQ images and films to show how imagery has been used to fight oppression.

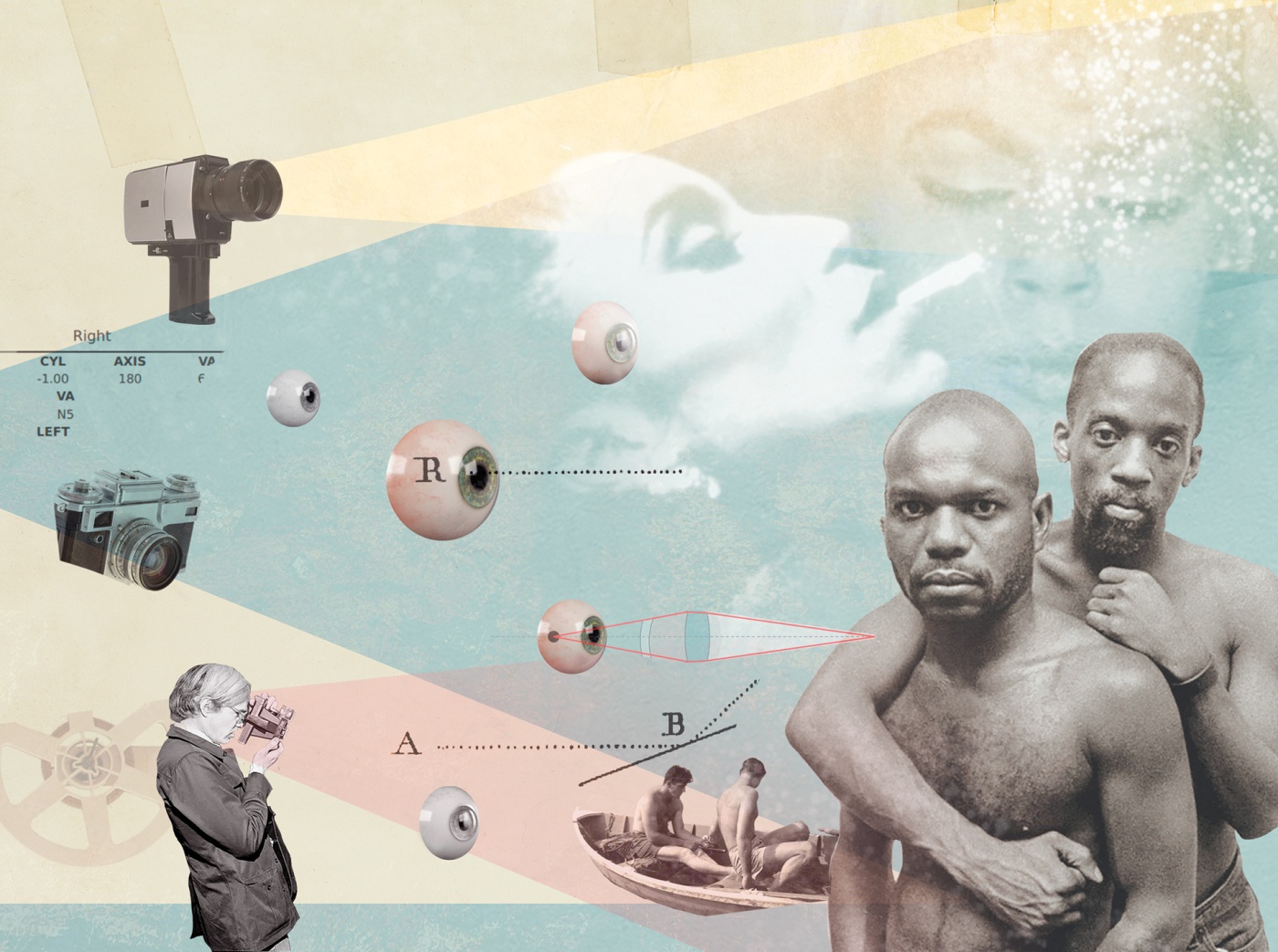

Tongues Untied, a groundbreaking 1989 documentary on the Black gay male experience, included elements of joy, community, eroticism, and sharp insider humor that were almost never seen on a public platform at that time. The work, which aired on PBS in 1991, used dance, poetry, music, and innovative editing (clips of men voguing, street protests, homophobic excerpts from Eddie Murphy standup and a Spike Lee movie) to push the boundaries of the documentary form. Religious right leaders pushed back—it showed up in an attack ad accusing President George H.W. Bush of using taxpayer money for “pornographic” work.

Directed by Black gay artist Marlon Riggs, who died of AIDS in 1994, Tongues Untied is part of what’s often called the New Queer Cinema, a body of work put out in the late 1980s and 1990s that powerfully broadened how the LGBTQ experience, especially among people of color, could be represented visually. In the collaborative piece, Riggs and fellow poet-performers Essex Hemphill (who also died of AIDS, in 1995) and Brian Freeman spoke lyrically about being the targets of both racism and homophobia, often simultaneously.

As a contemporary young queer Black man, Cole Francis ’26 had experienced some things touched upon in Tongues Untied—his Chicago-area public honors high school had routinely marginalized and tokenized the contributions of Black students, he said—but had never seen the film until his 2022 freshman fall at Brown, where it was part of Queer Visual Activism, a course taught by visiting professor Helis Sikk. The class presented iconic LGBTQ visual representations—from the 1980s photography of Nan Goldin to New Queer Cinema classics such as The Watermelon Woman—alongside seminal texts on sexuality, identity, and power (see sidebar). The point, says Sikk, was to invite Gen Z students into queer representations of decades past, showing how such images were used as tools of resistance against the prejudices of another era—and how such images can still project power and fight oppression now.

For Francis, the film was revelatory. “It helped me realize there’re so many facets to someone’s identity,” says the likely environmental studies concentrator. “I thought about Riggs making this documentary years before I was even conceived and being on a similar path to mine, trying to understand his own identity with so many different forms of adversity surrounding him.”

Delving into the film—and, more broadly, the class—was not just an exercise in self-knowledge for Francis, but a rigorous investigation of visual and narrative aesthetics and how they can be used both politically and artistically at the same time. “There are a lot of different skits within the film, some of them very comic, which make it very unique compared to what we consider a documentary in 2023,” he says. For his final assignment, he made his own very short video in a poetic Riggsian style, meditating on the tremendous pressure to fit certain beauty norms—taut, muscular, stereotypically “masculine”—on contemporary gay hookup apps such as Grindr.

That he came away from the film and the class both emotionally and intellectually charged was music to her ears, says Sikk, who is from Estonia. “I was just trying to explain the class to my mother,” she says, “telling her that it’s about the ways people have used visuals as activism to force social justice and advocate for their rights.”

But, she says, she also wanted the class to serve as a technical primer on how to read—or read into—visual language, which is why a key text was Gillian Rose’s “Visual Methodologies,” one chapter of which breaks down an image into its technical parts—composition, color, lighting, vanishing point—to understand how each serves its broader purpose. In our current social media world, she says, “we may look at 500 photos a day without knowing how to actually read them to understand how meaning is transmitted through visual elements.”

Collaboration or exploitation?

The class was also transformative for Nora Cowett ’24, a visual arts and gender and sexuality studies concentrator who says she was particularly struck by The Ballad of Sexual Dependency and other works by Nan Goldin, the photographer (and subject of All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, an acclaimed new documentary) who in the 1980s captured images of her New York City intimate friends, many of whom were societally shunned—heroin users and gay or transgender people.

For Cowett, the work—which Goldin originally presented at slide shows meant primarily for its subjects before individual images began selling into the hundreds of thousands of dollars—raised key art world issues of whether it was made in true partnership with its vulnerable subjects or was exploiting them. “I felt that, originally, she was making the act of photography a collaboration with her chosen family, who got to watch their own history unfold,” she says. “But that conclusion shifts when you think about where [commercially] the work has gone since.”

For her own class final project, Cowett took intimate photos of her own campus friends, eventually hosting a slideshow for them as Goldin did. She then interviewed them. “The ones I was closest to definitely felt like it had been an embrace and a validation, but others said they still felt uncomfortable,” she says. “Maybe there’s more at stake in having a photo taken now”—in a digital world where the image can quickly go viral.

Sikk says those are exactly the kinds of questions of representation, power, and historical legacy she wanted students to grapple with. “We covered a lot of history of LGBTQ culture that doesn’t necessarily get covered in high school,” she says, “and we engaged with some of the key thinkers of the late twentieth century, like Roland Barthes and Judith Butler. It pushed students to see the connections between the textual and the visual, and to be rigorously analytical about that. We kind of take it for granted, but that’s actually really hard to do.”