Trauma and Taste Buds

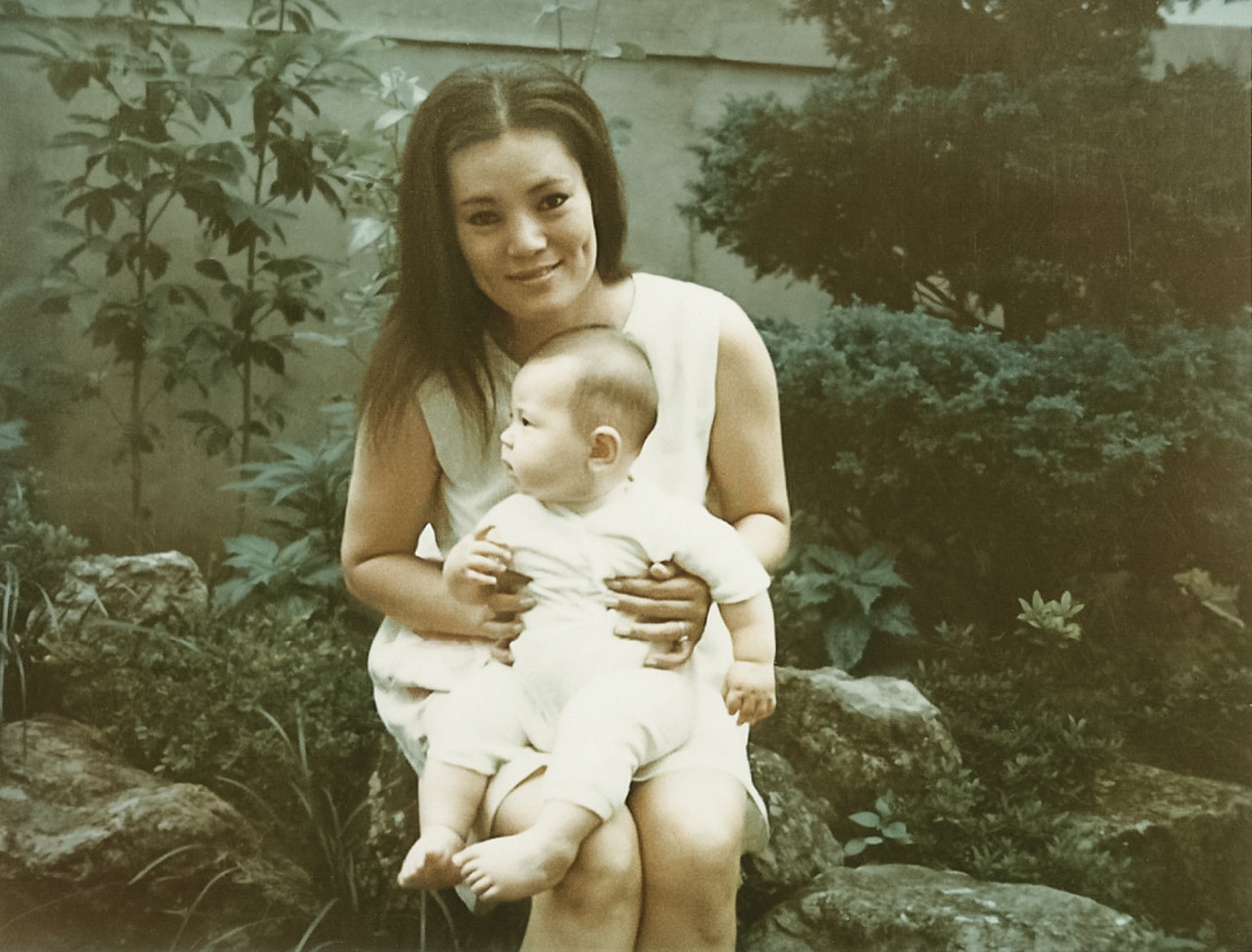

An acclaimed memoir recalls how Korean food kept Grace Cho ’93 connected to her mother

In 2008, Grace Cho ’93, a sociology professor at the College of Staten Island, was finishing her first book, Haunting the Korean Diaspora: Shame, Secrecy and the Forgotten War. She was also living with—and cooking nightly Korean meals for—her mother, a Korean war survivor who came to the U.S. with her American husband, Cho’s father. Cho’s mother experienced schizophrenia that kept her housebound for 20 years, fearful of the outside world and hearing voices. The last meal Cho made her, before she died, later in 2008: saengtae jjigae, a stew of fish, radishes, garlic, and red pepper flakes.

After her mother’s death, Cho remembered a time before the schizophrenia when her mother, virtually the only Asian in a small town in Washington State, ingratiated herself with suspicious white neighbors via her sense of humor, charisma, and hospitality, cooking for them and starting a business selling blackberries and mushrooms she foraged in the nearby woods. She had created a version of herself that masked her trauma, including a likely stint as a sex worker for U.S. soldiers.

Cho plowed her memories into Tastes Like War: A Memoir, a finalist for the 2021 National Book Award for Nonfiction. It’s a poignant, often funny page-turner about the complicated but unbreakable love between a mother and daughter. It provides a vital human lens into the growing body of research into the connection between schizophrenia and trauma. And it’s a testament to the powerful role food plays in triggering memory and forging intimacy amid pain.

The literary website Shelf Awareness called it “somehow both mouthwatering and heartbreaking,” which Cho likes, saying that cooking for her mom “allowed her to engage with a past she’d wanted to forget in a way that was safe and nurturing, because these were often foods that her own mother had cooked for her.”