Dashed

Tokyo, 2020: Olympics canceled due to COVID. Tokyo, 1940: Olympics canceled due to WWII. Star sprinter Ken Clapp ’40 had hoped to be there.

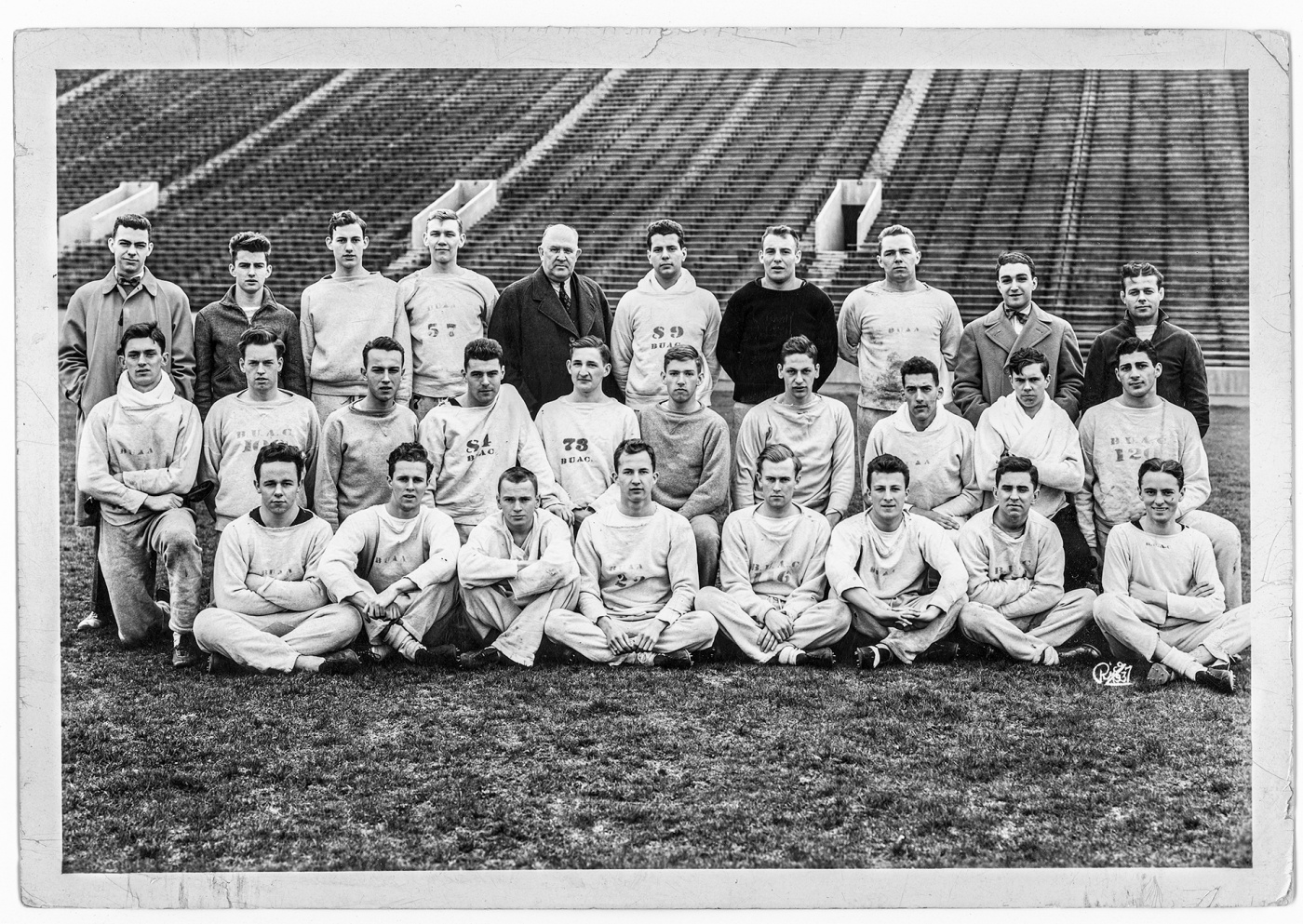

At Brown football games in the 1960s, fans might have noticed a tight-knit group of middle-aged alums and their families out tailgating and in the stands, with one former athlete, Bears sprinter Ken Clapp ’40, drawing a bit more than his share of attention. “He was still well known. You could just see people buzzing around him,” recalls his son Tim Clapp ’77, who often joined his parents on these Saturdays in Providence. Ken Clapp was greeted as he had been during his student days as “Rapid” or “Clapper” in this group of old friends and former athletes who counted Bears coach John McLaughry ’40 among their set. “Clapper” had gone the entire 1939 season without losing a race, shattering records and becoming 1939’s national champ for the indoor 60-yard and outdoor 220-yard dash. To anyone who attended Brown in the late 1930s and early 1940s, he was legendary.

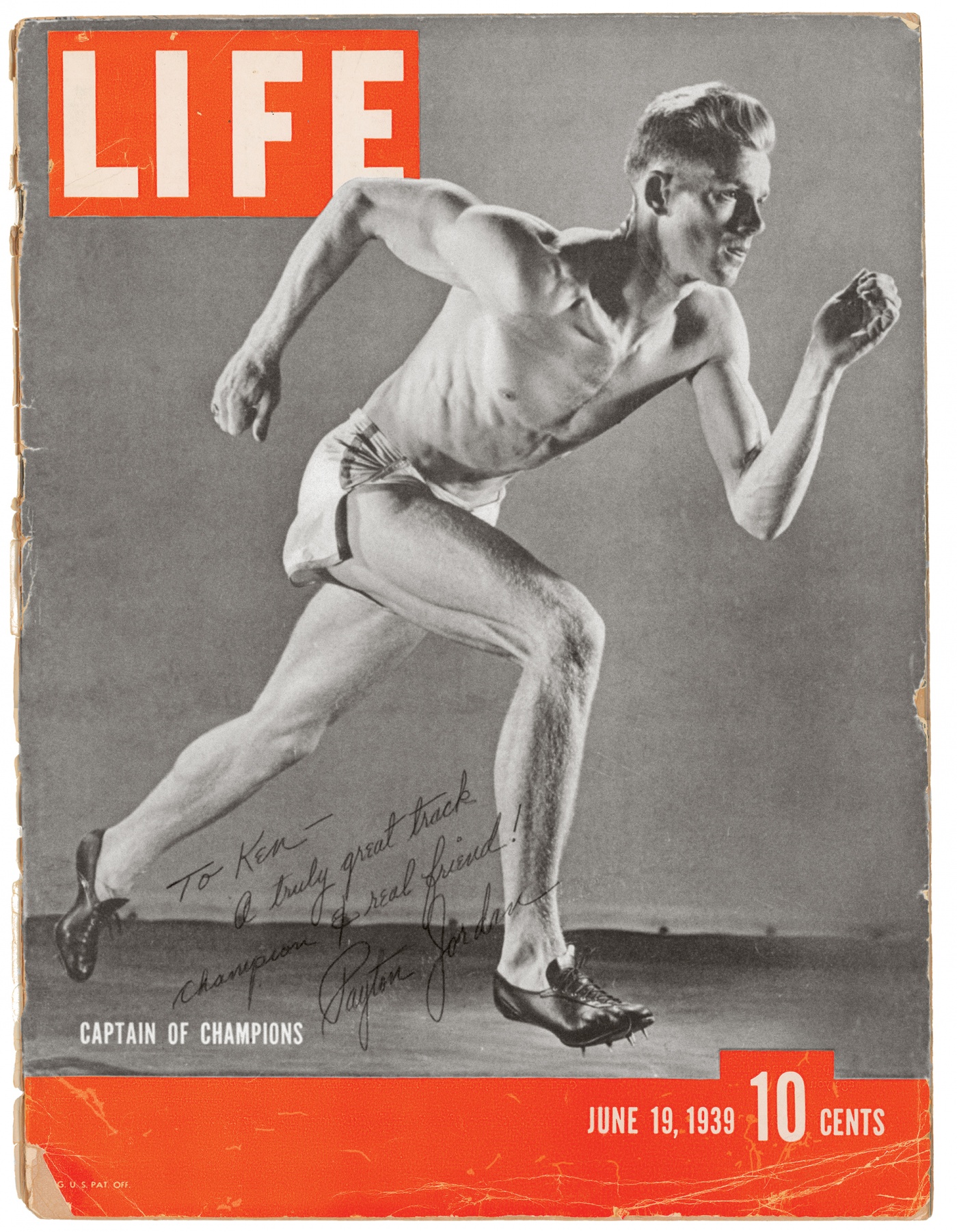

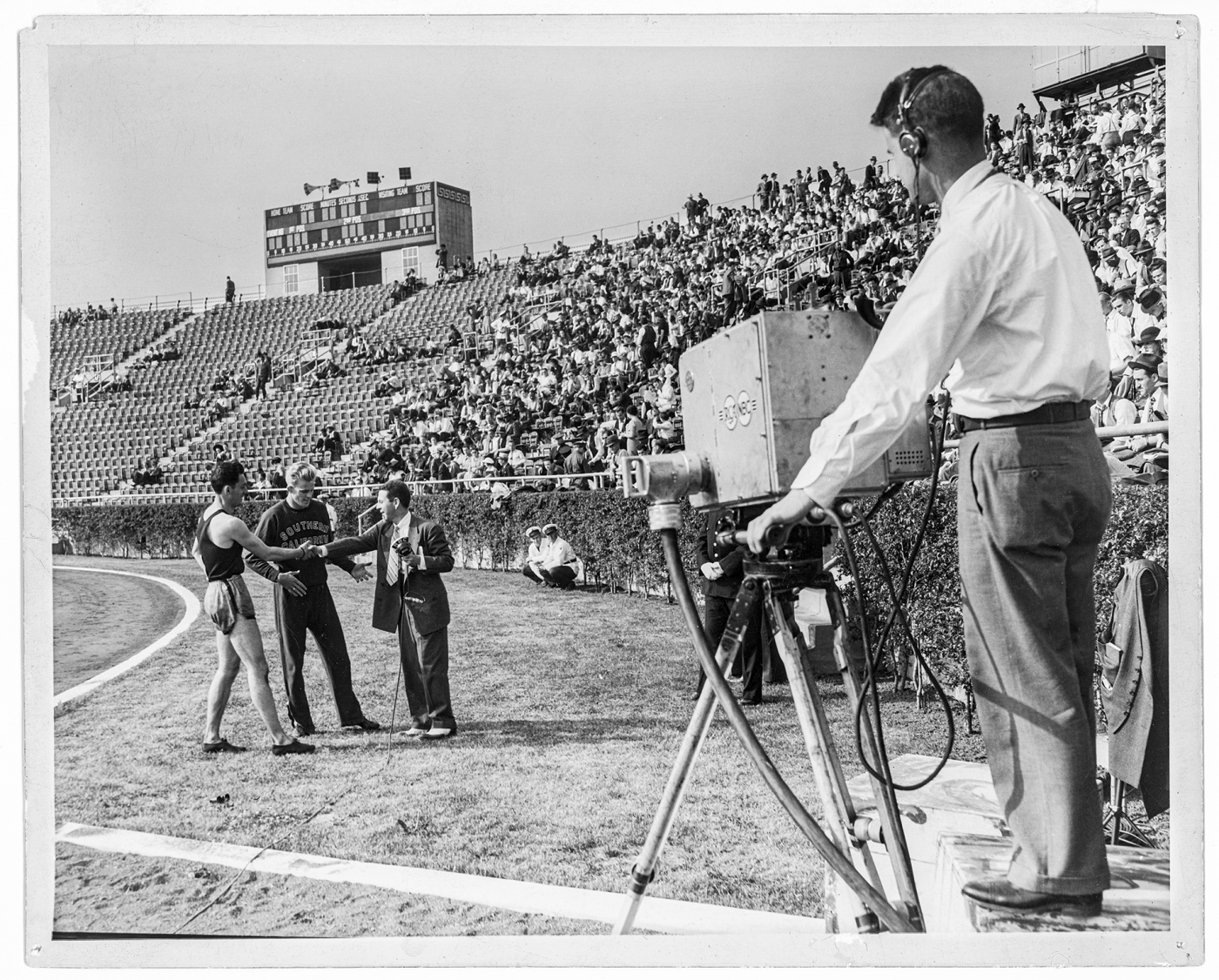

A key stop on Clapp’s journey was Randall’s Island in New York City, where on May 26, 1939, Brown and 33 other colleges competed in the first nationally televised track meet in U.S. history. The team to beat was the University of Southern California, which ultimately won the meet. Clapp’s big moment came when he beat USC captain Payton Jordan, who had been featured on the cover of Life magazine that week, by finishing the 220 yard dash in 21.2 seconds.

“It was not exactly an upset,” Tim Clapp reports. “My dad was already the reigning IC4A (Intercollegiate Association of Amateur Athletes of America) champ for the indoor 60-yard dash (6.4 seconds) and a seasoned national competitor. He would hold every Brown sprint record before he graduated in 1940.”

The meet wasn’t just important as a national showcase, the story in Life noted. Success there was expected to give athletes an inside track to the Olympic team.

Same for another event a month later, the national Amateur Athletic Union meet in Lincoln, Nebraska. Clapp was part of what was essentially an all-star team assembled by the famed New York Athletic Club to compete in the 4 x 100 meter relay, where the four-man team set a new A.A.U. record of 41 seconds. That would likely have positioned them for a trip to the games, Tim said, if they had gone on as planned.

Instead, 80 years before the coronavirus disrupted the sports world’s best laid plans for Tokyo 2020, the 1940 Olympic games—also originally set for Tokyo—were overtaken by larger events. In 1938 the games were moved to Helsinki because of conflict between Japan and China. Then came World War II, which forced their cancellation and ended the dreams of a generation of Olympic hopefuls—Ken Clapp among them.

Clapp had started running as a child. He grew up in Cambridge, Mass., just steps from Harvard, as the son of single mother Janet Mabie, an author and journalist with the Christian Science Monitor. Clapp would sell programs at university football games and play around on the field with other neighborhood kids. Some of the Crimson players took him under their wings, noticed his knack for speed, and encouraged him to get involved in sports, Tim Clapp says. High school took Ken Clapp to Moses Brown School in Providence, just down the street from the University. At Moses Brown, Clapp led the varsity track and field team to a state championship. His track success continued at Brown, with an eye toward qualifying for the Olympics.

Then came the cancellation. Clapp finished his English degree and went to work as a radio announcer in Boston, where he met his wife Barbara and joined the Navy as a lieutenant commander stationed on an aircraft carrier. Ironically, his son points out, Ken Clapp’s service in the Pacific theater was as close to Tokyo as he would ever come.

After the war, Ken and Barbara Clapp settled in Wellesley, Massachusetts, where they raised Tim and his three older sisters. Ken worked in advertising, on accounts including the Massachusetts Lottery and the Suffolk Downs race track. He finally did get to witness an Olympics in 1984 in Los Angeles, when he and Tim attended together and took in some track and field events. The couple retired to Cape Cod, and after a long and happy life together, died in 2006 just two weeks apart, Tim Clapp says.

His father didn’t talk a lot about his glory days, Tim Clapp recalls, but others did, especially at those Brown football games. Ken Clapp kept up a long-distance friendship with the man he beat that day on Randall’s Island, Payton Jordan, who went on to coach track at Occidental and Stanford and to be head coach of the legendary 1968 Olympic track and field team, which won 24 medals in Mexico City. Jordan autographed a copy of his Life magazine cover to Ken Clapp, calling him a “truly great track champion” and a “real friend.” From their lifetime of correspondence, Tim Clapp says, it is clear that Jordan was convinced his father would have gone to the Olympics, and that he hoped he would as well.

Yet Tim Clapp says his father never talked about what might have been with resentment.

“It wasn’t bitterness, it was regret,” Tim Clapp said. “He was very proud of his military service.

I think he was very grateful to serve his country. I think he would have been prouder to have served the United States of America as an Olympian.”

Stephanie Grace ’87 is a political columnist at The Times-Picayune | The New Orleans Advocate and a BAM contributing editor. She lives in New Orleans.