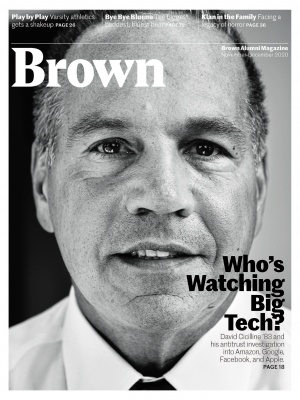

State of Play

This spring, Brown overhauled its athletics program. Varsity teams went club and vice versa, protests and lawsuits ensued, and some teams were reinstated—all in the shadow of the pandemic’s halt to competition. A look at the scoreboard.

The time stamp on the email remains etched in the mind of Kevin Boyce ’21: 12:04 p.m. on May 28, 2020.

Neither Boyce—a sprinter on the varsity men’s track team who saw the invitation to jump on a Zoom call with Brown Athletics while home in Columbus, Ohio, after a spring semester like no other—nor the 150 other student-athletes invited had any advance warning about why their cellphones were now buzzing.

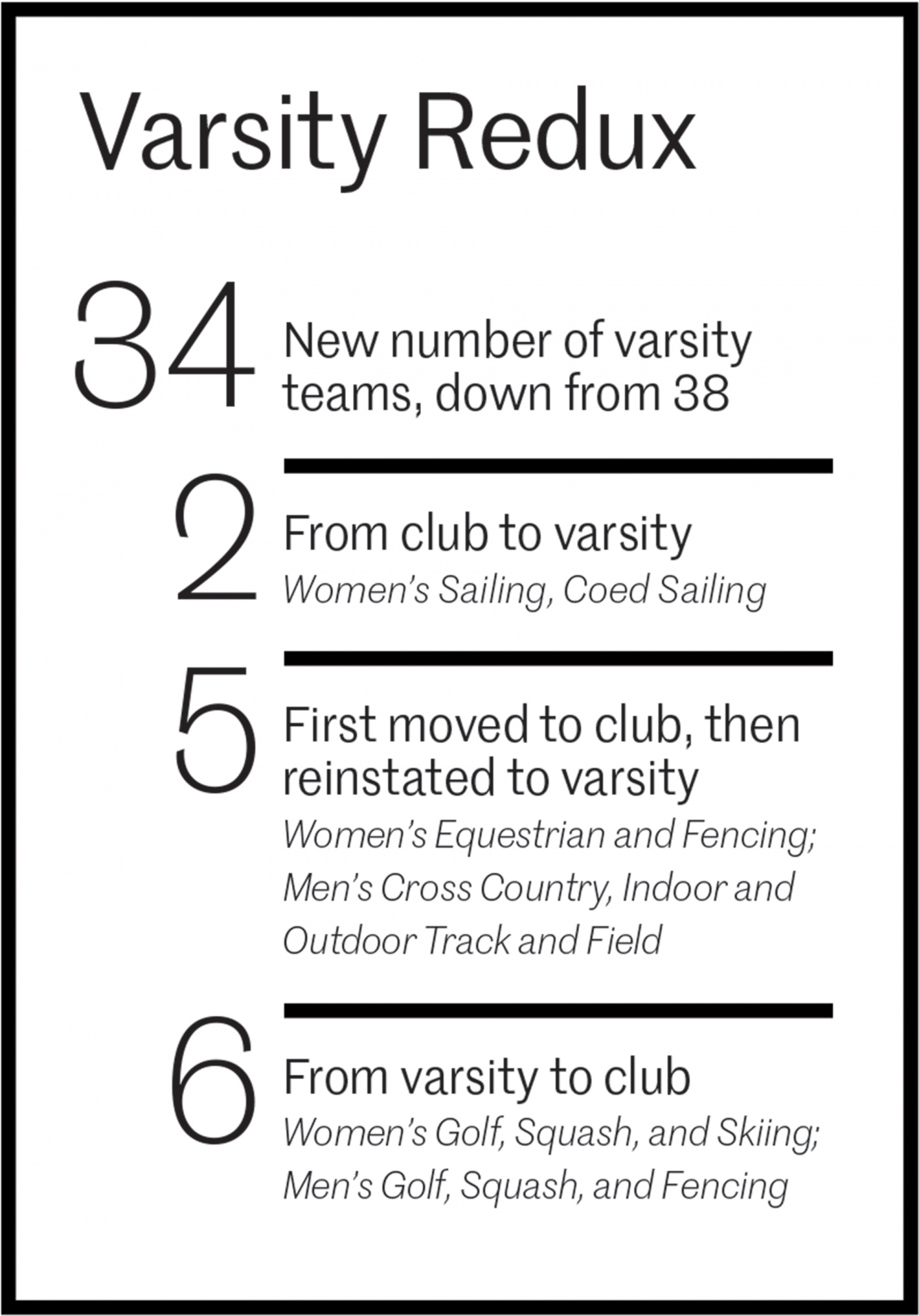

Boyce figured it was an update on COVID-19, which had already upended college sports. Instead, on the brief Zoom call with Director of Athletics and Recreation Jack Hayes, he learned his team would be dropped from Brown’s roster of 38 varsity squads and would transition to a club sport. Members of 11 varsity teams—men’s cross country and indoor and outdoor track and field, men’s and women’s fencing, men’s and women’s golf, men’s and women’s squash, women’s skiing, and women’s equestrian—received the same news.

“I was sitting there dumbfounded and devastated,” recalls Boyce. He and his teammates instantly began group-texting—now what? Fencer Anna Susini ’22 says one moment she had been focused on her team’s incoming recruits and her coach’s blueprint for imminent success in the Ivy League, and then the next moment, “all of that was ripped away.”

Meanwhile, the coed and women’s sailing teams learned they were transitioning from club to varsity status. Brown’s had been one of the few sailing teams competing at top level that was not a varsity team, according to a source within the dual crew, which effectively works as one entity except in competition. The women’s sailing team has won every national competition the past couple of years and recently included 2016 Olympics competitor Ragna Agerup ’20. A team spokesperson declined to comment publicly on their good news, given ongoing conflict around the changes.

For Hayes and Brown President Christina H. Paxson, this reveal of the Excellence in Brown Athletics Initiative was what they call a difficult but necessary step in a plan to create a winning sports culture on a campus where trophies have been few and far between. The Ivy League may be known worldwide for its academic excellence, but it was created as a sports conference—one in which Brown has stood out mostly for its large number of teams yet low rate of championships.

“Before these changes, we had the third-largest varsity athletics program in the country,” Hayes explains, “but the smallest budget in the Ivy League—which does not make sense if we are trying to give student-athletes the resources and experiences they need to be consistently competitive.” The varsity cuts were one part of a four-part plan, along with enhancing recruiting and building competitive roster sizes; taking coaching, training, and conditioning to the next level; and improving facilities. The overall objectives, Hayes says, are increasing varsity competitiveness, upholding equal opportunities for men and women, and enhancing club sports. Both Paxson and Hayes say they’d like to duplicate the success of club squads like Ultimate Frisbee, which won a national championship in 2019.

The groundwork for this shakeup was laid in the 2018-2019 academic year, when a consultant was brought in to assess the athletics program. University officials crunched the numbers and found all those varsity teams won just 2.8 percent of Ivy League titles in the decade from 2009-2018, the lowest in the league. “If Brown, as one of eight Ivy League institutions, won its proportional share, it would have won 12.5 percent of those championships,” Hayes wrote in an email interview. “That means we can and will do better.”

The grim stats led Paxson, in January 2020, to quietly form a seven-person, all-alumni advisory committee tasked with coming up with recommendations—with careful attention to diversity and gender equity among their charges. Brown’s Corporation approved the resulting plan this spring. “We look at this like building a great university,” Paxson said this summer in an email interview, stressing that Brown needed to make the smartest use of limited dollars for athletics. “You focus resources on the areas where you can be truly excellent. Brown takes that approach to academics and is applying that approach to athletics.”

University officials questioned offering a sport such as skiing at the varsity level in a state with no mountains, when promoting the two sailing teams—in the Ocean State, which for decades hosted the America’s Cup—made more sense.

The plan was announced as soon as it was approved, and when there was still a more than two-week window for athletes to transfer to other Ivies. But why the secrecy at the planning stage? Not even coaches had a clue changes were coming,

students say. Hayes says the University wanted the restructuring to be a data-driven process, not affected by emotions. Alumni have told the University over the years that it should reduce the number of varsity teams, “but the immediate follow-up is, ‘but not my team,’” Hayes says. “That’s just human nature. There is no universe where you don’t experience divisiveness and outright anger over which teams should be affected.”

“Here’s the playbook”

After the announcement, with Ivy League stadiums dark for fall amid the pandemic, the University tapped Joseph Dowling III, chair of the Brown Investment Office, to head a strategic planning effort to build what he calls “a high performance culture” within athletics. “I said great!” Dowling remembers. “So here’s the playbook. The playbook is you go in and you interview everyone, every coach, assistant coach, administrators, maintenance….” He and his team also analyzed three years of lengthy player surveys, he says.

Dowling—a Harvard squash player who grew up in Providence in the stands of Brown football games with his dad Joseph Dowling Jr. ’47—is credited with outperforming the school’s rivals with what had been the Ivies’ smallest endowment when he was hired in 2013. He told the BAM he restructured the endowment staff to 50 percent women because diverse perspectives have been shown to improve performance. Now he wants to use the same data-driven, best-practice formulas to bring a higher return of championships to the school’s athletics.

“We hope to bring some Moneyball techniques to athletics,” Dowling says, referring to the 2003 Michael Lewis book and subsequent film that sparked a revolution of computer analytics in pro sports. Dowling cites five parts to his plan: invest more in athletics, with funds to be raised specifically for this goal; enhance “cross-communication” for teams and coaches to share winning strategies; set goals and increase accountability; invest in coaches and their training; and better integrate the University’s academics with athletics. “We have data science—we should be utilizing that. We have one of the best psychology/mindfulness professors in the world,” Dowling says. “It’s the Building on Distinction playbook for athletics,” he adds, referring to Paxson’s 10-year strategic plan, launched in 2014.

Dowling, whose team will announce more details in coming months, plans a town hall meeting with coaches to present his findings and says transparency will be his byword. One of the “cross-communication” opportunities he hopes to tap involves women’s soccer coach Kia McNeill, who in 2019 led the Bears to their first Ivy title and NCAA appearance in 25 years. “She’s one of our highest performing coaches,” he says, and “we’re not giving her a platform to share her philosophies and strategies around recruiting, around coaching, around attracting people to Brown.”

Brown turned out to be at the crest of a wave of varsity trimming. Several Division I universities announced cuts in April. Then, in July, Stanford—citing budget problems from before the coronavirus—announced its lineup of 36 teams was going down to 25. Most of the dozens of other colleges that dropped varsity programs over the coronavirus summer of 2020, including Dartmouth, targeted what some call “country club sports” such as squash, fencing, golf, or rowing. Meanwhile, thanks to reinstatements Brown made after student and alumni pushback and a lawsuit, its new roster of 34 teams will mean Brown, along with Harvard, will field the highest number of varsity teams in the country. Even so, says Hayes, the net reduction will position Brown Athletics for a more competitive future.

That future will be soon, if Dowling has anything to do with it. “In five years, I want our program to be top of the Ivy League,” he says, noting that if he’d said that when he arrived to work on the University’s investments, “they’d have laughed me out of the office.” Brown’s Investment Office brought its endowment performance up to number one in the Ivy League and, last year, to number one in the nation.

A major reversal

In group texts that started even before the call with Hayes ended and went on for days, athletes did what they’ve been trained to do: Fight back.

Jordan Mann ’15, a former track and field team member who now is a volunteer coach, said he was out with a friend when he looked at his phone “and there were like 800 texts”—only a slight exaggeration. Like many Brown sports, the teams had seen their struggles, with men’s indoor track and field placing last in the Ivy right before the coronavirus shutdown, but Mann also noted “we had multiple people qualify for NCAA regionals.” Indeed, University officials acknowledged that a key driver of the decision to cut the teams was not so much their records as the need for gender balance.

To Mann and other advocates, downgrading men’s track in pursuit of gender equity showed a blindness to what the sport meant for other diversity. Statistically, the teams, taken as a whole, had the third-highest rate of Black athletes on campus, after football and basketball. For Mann, running is a doorway for academically talented kids from disadvantaged backgrounds who otherwise might not have even heard of Brown. “There’s no one who plays squash,” he says, “who says, ‘I didn’t know what Brown was until somebody told me.’”

Ironically, one key testimonial came from an Irish alumnus, the distance runner Kevin Cooper ’13. In an impassioned essay for New England Runner, he described his roots as the son of a house painter, his pride as the only Irish citizen in his graduating class, and his deep frustration over this proposal for a varsity sport that had been his door to the American Dream. “Running,” he wrote, “never cared that I was working-class.”

For Mann, running is a doorway for academically talented kids from disadvantaged backgrounds who otherwise might not have even heard of Brown.

The outcry spread. A key source of support came from Brown’s women track athletes—even though their squad was not downgraded—who said the camaraderie between their team and the men had been an integral part of their college experience. “It hurt me to see the men’s team cut,” said Brynn Smith ’11, an Ivy League champion hammer thrower who now teaches school in Baltimore. Smith, recalling how sports had connected her to Brown and how the men’s and women’s teams had been like family at away meets, said track, “for many underrepresented groups, was giving access to a predominantly white and elite institution.”

Within hours, Smith and Mann found themselves among the unofficial leaders of a campaign to reinstate the teams that grew quickly through platforms like Facebook, GroupMe, and a series of Zoom calls. The crusade’s level of organization—with committees created to lobby, coordinate letter writing, and conduct supportive research—and its ability to plug into a global network of highly resourced Brown alums eventually captured national attention through a profile in the New York Times. But advocates say their sophisticated effort still might not have succeeded were it not for the May 25 police killing of George Floyd.

The same night as the Hayes Zoom call, protesters in Minneapolis occupied and burned a police precinct house, a gathering storm that soon mushroomed into a nationwide movement against structural racism. At Brown, those protests powered an argument that the University was demoting teams that had a larger number of Black athletes than most others.

On June 10, less than two weeks after the initial Zoom call, Paxson announced a reversal and a reinstatement of the three squads. The president said in an email interview, “I don’t think there is any question that the horror and tragedy of George Floyd’s killing shaped the stories shared with us about the importance that track and field and cross country had on the student experience at Brown,” adding that testimony about the impact on women’s track and field also played a role. More reinstatements would follow.

To the courts

A group of Brown squash players filed suit against the University in late May. According to Legal Radar, the breach-of-contract suit “accuses the defendant of concealing plans for termination of the sport from students before they decided to attend Brown, thereby depriving them of opportunities to play for other elite universities.”

Should success be measured—arguably, in the spirit of the Open Curriculum—by the number of opportunities to compete? Or should the focus be images of Bears hoisting trophies?

In late September, by press time, the squash lawsuit was still making its way through the system. Players interviewed by BAM said the University’s vague words about boosting support for club sports rang hollow. In addition to losing access to varsity-level training facilities, the teams feared at the club level they’ll be raising money for costs currently covered by Brown for everything from bus travel to uniforms. The level of competition will drop off sharply, they said, while scheduling opponents will be tougher, and their best athletes would lose their chance to win an Ivy championship or compete in the NCAAs.

A month later, in late June, the Rhode Island ACLU filed another suit, alleging that the reinstatement of men’s track and field and cross country meant the reshaped initiative now violated the 1998 settlement to an earlier lawsuit, Cohen v. Brown University (see page 31). The ACLU demanded the reinstatement of five women’s teams.

By late August, court-mandated discovery proved embarrassing for the University when emails showing conversations between Paxson and others about using the controversy as a means to petition the court to end the Cohen agreement were released by the plaintiffs and made headlines. In one email thread—which discussed the latitude other Ivy schools take in matching the gender balance of their athletic rosters to that of their overall undergraduate population—Chancellor Samuel Mencoff had told Paxson that anger over squash and, at the time, track could be “a way to end this pestilential thing.”

More news stories followed, but on September 17, both parties in the ACLU-led Cohen lawsuit announced a proposed settlement in which the Cohen Joint Agreement will terminate on August 31, 2024—leaving Brown still fully subject to Title IX, but without additional restrictions. The big news for affected athletes: under the settlement, Brown restored women’s equestrian and women’s fencing to varsity status.

The joy of reinstatement

Equestrian rider and team cocaptain Lauren Reischer ’21 was born with a form of cerebral palsy that initially left her unable to crawl, let alone walk. She’s been riding since childhood, and her story as a disabled varsity equestrian rider,

who also works with the therapeutic program GallopNYC, has been highlighted by Brown. She was baffled by the initial May decision to move her sport to club status.

“The team could not be more inclusive and more welcoming,” Reischer said at the time. She explained that like a few other Brown teams, you can join with no experience and learn as you go. “It’s rare that you hear a disabled person and sports used together in the same sentence. And what I had felt is that Brown Athletics, by including me, has been paving the way to change the narrative around what it means to be an NCAA athlete.”

Reached in late September, after the reinstatement, Reischer was giddy. “I’m so overwhelmingly happy to be reinstated, it’s hard for me to think of anything else.” She points out that Brown’s continuing varsity support makes the team accessible for new riders and those who can’t afford horses or the transportation and equipment costs. “It would probably come out to two thousand dollars per person per semester,” she says.

It’s an observation that blows open the same question the initiative set out to answer: What does excellence in Brown sports look like? Should success be measured—arguably, in the spirit of the 51-year-old Open Curriculum that celebrates experimentation and individuality—by the number of opportunities to compete? Or should the focus be on images of Bear teammates hoisting trophies, augmenting the University’s national reputation for academics and campus life?

Why athletics, anyway?

Brown has arguably been grappling with these questions since the official formation of the Ivy League in 1954—Brown was the last to join—and certainly since the 1970s, an era highlighted by the 1972 federal civil rights law that established Title IX, mandating gender equality.

Brown women’s crew won the Ivy title in 1974, the first year for female championships in the Ancient Eight, while women’s track and field won a championship in its second year as a varsity sport in 1978, and women’s soccer dominated the Ivies in the 1980s.

“The holistic benefit to the most neglected aspect of Brown’s culture over the last seven decades is unassailable.

But in the highest-profile men’s sports, apart from occasional breakout moments—men’s ice hockey reached the NCAA Frozen Four in 1976, for example—the Bears never really sustained a level of success to match Brown’s rising profile as an academic institution in the first decades after instituting what was then called the New Curriculum.

Over the decades since Title IX and the Cohen case, Brown’s varsity teams—both men’s and women’s—proliferated to a point that the administration found unsustainable. Yet in 2011, then-President Ruth Simmons shelved a recommendation to downgrade four varsity programs amid community backlash.

For some alumni, it’s long been a source of frustration. Kevin A. Seaman ’69, former golf team member and Brown Daily Herald sports editor and the “biggest fan Brown sports has had for the last 55 years,” wrote to the BAM to express kudos. “Finally,” he wrote, “Brown has recognized that by focusing on a more realistic number of programs, it can hope to achieve the success that all of its sister schools, relative to Brown, have attained…. The unfortunate, but expected, pushbacks have occurred, but the holistic benefit to the most neglected aspect of Brown’s culture over the last seven decades is unassailable and forever welcome.”

To current golf team member Pinya Pipatjarasgit ’22, who argues Brown should have phased in the changes so she and her teammates could finish their varsity careers, winning shouldn’t be the whole story. Brown Athletics should be about “teaching students how to build character and creating a bond with the school,” she says.

“I see that side,” says Dowling. But “you’re only given so many resources.” He compares the sports strategy to Brown’s academics: “We could have a lot more classes if we hired teachers that weren’t as great; if we lowered standards.”

In a letter to the Brown Daily Herald, golf consultant Brendan Ryan offered an insider’s view of the golf landscape, which he says is increasingly competitive at both varsity and club levels. “Many schools now make academic accommodations in recruitment,” he wrote. “At Brown, from my observations, the academic standards for women’s golf are amongst the highest requirements for student athletes. This privileges an exceedingly small group of potential recruits ... and has led Brown women’s golf to fall behind.” Pipatjarasgit countered that despite recent struggles, the team won awards just two years ago—and “has been an important source of Asian American representation in Brown athletics.”

Hayes says that overall, “Multiple teams that have the highest diversity, in terms of students from historically underrepresented groups and socioeconomic diversity, have maintained varsity status, while some sports that were among the least diverse transitioned to club.” Going forward, he adds, diversity will be under renewed focus in recruiting. And even as the initiative has morphed, “we expect the representation of students from historically underrepresented groups to remain comparable to the approximately 20 percent prior to the launch of the initiative.”

“We understand the frustration and sense of loss that some of our student-athletes are experiencing,” Paxson says. But she points out that it’s “the University’s responsibility to make the best decisions,” even when those decisions are hard. And perhaps no words, no promises of future glory, could console students for whom varsity sports has been central to their Brown experience, and whose teams are varsity no more.

Reaction from alumni has been mixed. Roger Sherman ’69, part of a seven-person committee of alumni, parents, and students seeking to overturn the changes, questions the value of the savings—initially estimated at 2.5% of last academic year’s $19.9 million athletics budget, although COVID impacts meant Brown hadn’t released a new figure by press time. The group wants a transparent approach and a seat at the table for future athletics planning—and has also asked the Ivy League to set spending caps to address what Sherman calls a “competitive imbalance” between Princeton, Harvard, and Yale and the other Ivies. “We seek...to give all the schools with fewer resources more opportunities to compete successfully,” he says.

Genine Fidler ’77, who played varsity lacrosse and squash and later became a University trustee, was not involved in the initiative but supports it. Of fielding 38 varsity teams, she says, “we can’t fulfill the mission when we’re spread that thin. It’s important to view the changes within a larger context. The university needs to maintain the ability to be flexible and respond and change and grow.”

For Lisa Caputo ’86, who led women’s field hockey to an Ivy League title before a high-profile career in communications, the initiative “makes logical sense” as a first step toward the kind of success that made a difference for her experience at Brown and her path afterward. Winning “gave me the tools I needed to succeed in the workforce,” Caputo says. And she believes that’s true for club sports, too: “They’re not losing that opportunity. The thrill of victory—and to be a convenor for fans—is a big deal.”

Caputo takes a long view. She recalls coming back for her 30th reunion when the entire campus was electrified by men’s lacrosse playing in the NCAA Final Four that weekend. “There was a sense of pride—you can’t underestimate what that does for a university,” she says. “Brown should be the best of the best in as many areas as it can be, and athletics is one of them.”

Will Bunch ’81 is national opinion columnist for the Philadelphia Inquirer and Daily News and author of several books including Tear Down This Myth: The Right-Wing Distortion of the Reagan Legacy. Additional reporting by Louise Sloan ’88.