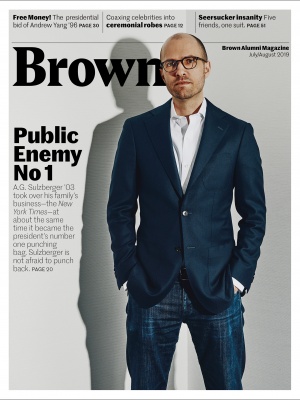

Andrew Yang Wants to Give You $1,000

Serial entrepreneur and erstwhile political nobody Andrew Yang ’96 has leveraged social-media savvy and a Big Idea—universal basic income—to create a surprisingly successful presidential candidacy.

It was a gray, blustery Monday night in mid-April, with a chilling dagger of wind whipping off the Potomac River that touched 50 mph. It felt like the odds of anyone showing up for an outdoor rally on the steps leading down to the Reflecting Pool at Washington’s Lincoln Memorial on a night like this were about as good as those that the speaker—an until-recently obscure entrepreneur, Andrew Yang ’96—will become the 46th president of the United States.

And yet the people came. Ransom Fox, an 18-year-old high school senior from Fairfax, Va.—wearing a big red-and-white bandana and clutching a hand-drawn sign that read “Protect Our Jobs—Yang Gang 2020”—and a couple of his schoolmates had scoped out prime real estate on the steps an hour ahead of time.

Fox is a self-described “Trump supporter” and son of a GOP functionary in northern Virginia. But the teen told me he’s now pumped about Yang and his ideas after stumbling across a YouTube video in which the 44-year-old political neophyte had talked about proposals like the “Freedom Dividend,” a $1,000-a-month government check to every American over age 18, on a wildly popular podcast with Joe Rogan, an Ultimate Fighting commentator.

“I see similarities [between Yang and Trump] in that they both want to protect our jobs, they just have different views about protecting [them],” Fox said amid the gusts. He added: “I will vote for Yang in [Virginia’s open] primary. If he makes it to the top”—a general election against the incumbent president—“I don’t know what to do.”

Fox is not a total outlier—Yang’s insurgent Democratic primary bid has appealed to other conservative voters—but as the steps fill up toward an eventual crowd of about 1,000 you tend to meet more traditional Democrats, libertarians, the previously apolitical, and a few who voted in the 2016 primaries for the democratic socialist Sen. Bernie Sanders. The only thing this mix of committed supporters and the Yang-curious seemed to share was a thirst for new political ideas to shatter Washington’s political ennui … and a fondness for numbers.

“Andrew says a lot about math,” a rally organizer shouted into a microphone as the 6 p.m. start loomed. “Who’s got a “MATH” sign?” About 50 or 60 people held up the blue placards. “So when Andrew says something about math, hold up those signs and yell, “Math!”

Fifteen minutes later, the candidate finally bounded onto the steps, energetic and fashionable in a red and blue scarf and a black baseball cap that read—you guessed it—“MATH.” Just a stone’s throw from where Dr. Martin Luther King delivered his 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech, Yang laid out a 21st century nightmare of robots and artificial intelligence taking away the jobs of truck drivers, store clerks, and call-center workers. But then he pivoted toward a more hopeful message—punctuated by his $1,000-a-month plan, which he tells the rally has already been tried successfully in one American state.

“What state is that?!” Yang shouts into the mic.

“Alaska!” shouts back the crowd, obviously well-schooled from YouTube.

“And how do they fund it?!”

“Oil!”

“And what is the oil of the 21st century?”

“Technology!”

“In Alaska they call it the Oil Check and they love it,” Yang says after the hubbub stops echoing off the Reflecting Pool. “We’re going to call it the Tech Check and we’re going to love it. I want you to think what you would do with $1,000 a month ….”

Andrew Yang isn’t leading in the polls, and with big names like former vice president Joe Biden continuing to enter the ever-expanding Democratic fray, the math for actually winning the party’s nomination at next July’s convention in Milwaukee, let alone defeating Trump in the 2020 general election, remains beyond daunting. But Yang’s bid for the White House has arguably been the most unconventional and even the most interesting in this rugby scrum of nearly two dozen candidates.

And on most days it’s the most fun—a point he hammered home in mid-April when the campaign posted a video of a hologram of Yang showcasing his moves alongside a similarly beamed-up Tupac Shakur, the late rapper, while promising Yang might later show up at campaign rallies in holographic mode. (Ribbed about it during a CNN Town Hall, he said to the host, CNN anchor Ana Cabrera, “How do you know it’s me in this chair?”)

Given the admittedly low expectations for a not-well-known businessman who’s never run for any political office before, it’s fairly remarkable how far Yang has already ventured on the long, strange trip of a modern presidential campaign. Polls in the spring showed Yang running as high as 3 percent in the crowded field, ahead of well-known pols like senators Cory Booker and Kirsten Gillibrand—and internet prediction markets rated his chances even higher. Hundreds of thousands of TV viewers saw Yang hold court for an hour at that CNN Town Hall—a warm-up for June when, aided by his skill in raising small donations, he seemed certain to qualify for a spot on the Democrats’ first big debate stage in Miami.

The fact that Yang aims to be America’s first Asian-American president almost feels like an afterthought—a tribute, perhaps, to his ability to keep the conversation focused on the proposed Freedom Dividend and some of the 95 other policy positions on his website. The national attention is fairly heady stuff for the son of Taiwanese immigrants from upstate New York whose unusual and small do-good-capitalism nonprofit, Venture for America, was little publicized before Yang launched his Oval Office bid.

“What I’m proposing is something called human-centered capitalism,” Yang said as he dug into a salmon Caesar salad in the large lobby of a Capitol Hill hotel, still on something of a high from the CNN event the night before and the newest poll showing him moving ahead of some more famous Democrats. He explained that means “we channel the market’s ability to direct resources—but instead of trying to maximize profitability in stock market prices, we try and maximize our own health, our life expectancy, our mental health, our freedom from substance abuse, our environmental quality, our childhood success rates—things that would actually be important to us.”

Yang’s wonky passions, for ideas and for giving something back to society, were honed during his four years on the Brown campus in the mid-1990s. His parents were lured from Taiwan to America by a program in the late 1960s that encouraged the island nation’s best and brightest to study in the U.S. on a fast track to legal residency. After meeting and marrying at Berkeley, his dad—a physicist with multiple patents as a researcher for General Electric and IBM—and his mom, now an artist, settled in Schenectady, N.Y., where Andrew was born in 1975, before the family moved to Westchester County, N.Y.

In The War on Normal People, the second of his two books, Yang writes with searing honesty about his childhood and the abuse heaped on him for his Asian heritage—the kids who called him “Chink” or kicked at him like he was an extra in a kung fu movie. Enrolling at Brown—he’d nearly attended Stanford before deciding last-minute to stay on the East Coast, near his brother who was at Wesleyan—gave Yang more oxygen to be himself and find new outlets for a passion for helping the underdog that he’d developed during the years of bullying.

“There was a program where they teach you about marginalized people of various kinds,” Yang recalled in the interview. As he learned more about the plight of black and brown Americans, the LGBTQ community, and women, “It had a huge impact on me.” He also learned more about himself. As a suburban kid, he says, “there was something of a monoculture with just three TV channels back in the 1980s—so there was a bit of an awakening to my own identity I went through at Brown.”

Meanwhile, Yang’s studies in political science and economics look today like a roadmap to the presidential campaign he’d create a quarter-century later—including labor-force economics, where his obsession with the future of work emerged. (He’s continued to stay in touch with the professor, Ross Cheit.) But Yang’s Providence years were kind of low voltage for a future presidential candidate. He’s called himself “a fairly unremarkable student” who spent much of his time playing video games like Street Fighter II and working out, focused on the martial art of taekwondo. He jokes in his first book, Smart People Should Build Things, that his big college achievement was bench-pressing 225 pounds eight times in a row and building up his pectorals to the point where he named them “Lex” and Rex.”

Polls in the spring showed Yang running as high as 3 percent in the crowded field, ahead of well-known pols like senators Cory Booker and Kirsten Gillibrand.

After graduation, Yang earned his law degree at Columbia and endured a short, unsatisfying stint as a corporate lawyer. He then launched one internet startup that failed to take off but then did much better with the next one, a business-school test-prep company called Manhattan GMAT that he and his co-founder sold in 2009 to the industry giant, Kaplan, at a healthy profit. By then, he’d noticed that ambitious entrepreneurs like himself tended to congregate in a few large cities and a few elite professions while the rest of the U.S. economy was suffering—but he wasn’t sure what to do about that.

In 2008, Yang had returned to the Brown campus for an alumni panel on entrepreneurship where he met Charlie Kroll ’01 for the first time. Kroll’s story of how he’d built a small but thriving financial software startup amid the industrial brownfields of Providence didn’t just inspire Yang but gave him a big idea, a venture-capital outfit that targeted down-and-out Rust Belt cities. He imagined it like the Bill Clinton–founded Teach for America except with entrepreneurs—so much so that he called it Venture for America when it launched in 2011.

“I decided to create more Charlie Krolls,” said Yang, who in nearly a decade with Venture for America has launched small success stories like Banza, a publicity savvy startup in Detroit that makes chickpea pasta, and LeagueSide, also in Detroit, which connects struggling youth sports leagues with big-name corporate sponsors. Kroll, who joined VFA’s board of directors, said that Yang “is really magnetic. He has this almost unique ability to inspire people and get them motivated to do things.”

After Trump’s election in November 2016, Yang started to ponder how he could do more. Convinced that automation of factory jobs in the Midwest had driven voters to the Republican party, Yang became interested in the idea of universal basic income (UBI) as a safety net against a robot economy. He met one of UBI’s top advocates, longtime union leader Andy Stern, and asked Stern who would make that the focus of a 2020 White House bid. When Stern told him, flatly, “No one,” Yang says he decided to run himself. (He later told CNN that his mother’s initial reaction was along the lines of, “That’s nice … pass the salt.”)

“I’m surprised someone had the courage,” Stern said in an interview, adding that he never imagined a candidate who’d have so much success using new media like podcasts and YouTube to bring so much attention to UBI.

Yang said in the interview that no one imagined that 21st century capitalism “would be eaten by itself.” The biggest problems, he explained, are advances in automation and artificial intelligence. “In the old days you’d say in order to optimize my bottom line I’d hire the best people and treat them well,” he said, “but increasingly, optimizing my bottom line means getting rid of people as fast as possible.”

His candidacy has been marked by that type of big-picture thinking. But instead of being a single-issue candidate, Yang created a website with a veritable matrix of policy issues. They range from the serious—on health care and drug-policy reform—to rather arcane political topics like a text line for reporting robocalls, getting rid of the penny, protections for MMA (mixed martial arts) fighters, and free marriage counseling. He backed away from another early stance—opposition to circumcision—after pushback and some ridicule in the press.

“A lot of it is just clarity of vision and giving people a sense of my world view,” he said of his 96 listed positions. Meanwhile, Yang’s direct pitch for Trump’s disgruntled 2016 voters has had an unintended consequence: winning the candidate favorable reviews from a few prominent white nationalists in the Trump-friendly movement that bills itself “the alt-right.” The notorious white nationalist Richard Spencer tweeted that “Trumpism was the fantasy that America can be we saved [sic]. Yangism is the awareness that it can’t.” At the same time, #YangGang hashtags exploded on underground sites like 4chan, popular with the far right.

Yang told me he’s repudiated any white-extremist support but that he’s also not worried about it. “One thing I’ve learned running for president is that you have to lean into who you are,” he said. At the Lincoln Memorial rally, his campaign introduced him with a steady stream of young supporters who voiced both their angst about making ends meet in 21st century America and their hopes for what they could do with a Freedom Dividend of $1,000 a month.

“The 9-to-5, lifetime careers of our grandparents are virtually non-existent in today’s America,” a local artist and Yang volunteer named Rachel Spellman told the rally as she spoke of trying to survive on short-term gigs and freelance work. She added that her family had disowned her for coming out as gay and “Andrew Yang is the only presidential candidate right now who would offer protection in scenarios like mine.”

Others in the rally crowd were curious about Yang but not ready for commitment. Lisa Winett, a 47-year-old teacher from Baltimore, told me she thought the candidate was “pretty smart,” yet she wondered about giving $1,000 a month to the drug dealers currently preying on her hometown. And if the Freedom Dividend gains too much traction, she said, “Big Business is going to squash that like a bug.” Some critical economists say Yang’s plan won’t do enough for the poorest Americans, because the $1,000 would merely replace their current benefits, like disability checks.

For now, though, Yang is flying in a sweet spot above the ground yet below the radar screen. His spring tour of rallies proved an ideal platform to talk about his quirky-but-popular issues like ditching the gross domestic product, or GDP, as a measure of America’s economic health. He explains that GDP measures whether corporations are thriving but not people, at a time when opioid addiction is rising and U.S. life expectancy is actually declining. He questioned why the annual State of the Union speech doesn’t reflect that.

“I’m going to present them as a PowerPoint deck—I’m going to be the first president to do that!” he told his cheering admirers. “That’s right—you’re going to get something out of the State of the Union instead of these bizarre theatre performances we’re subjected to every year … and people are all trying to stand up and clap or not clap—what is this? It’s so weird!”

Yang looked out into the grey gloaming toward the Washington Monument, his view of the great Reflecting Pool blocked by dozens of whooping supporters waving their signs that read “MATH.”

“Numbers, right?!”

Will Bunch ’81 is national opinion columnist for the Philadelphia Inquirer and Daily News and author of several books including Tear Down This Myth: The Right-Wing Distortion of the Reagan Legacy.