One day in 1966, a young Columbia graduate student was at a gym when he noticed a man walking at a blistering pace with a quirky gait. Curious, Thomas Eastler ’66 introduced himself and asked, “What are you doing?” The answer shaped much of his life.

The walking man was Shaul Ladany, a two-time Olympic racewalker from Israel. Over the ensuing year he taught Eastler how to walk the walk: one foot always appearing to touch the ground and one knee kept straight, hips twisting as much as 20 degrees. While the stride looks ungainly and comical, those who master it can fly around a track: Olympic racewalkers routinely break seven-minute miles.

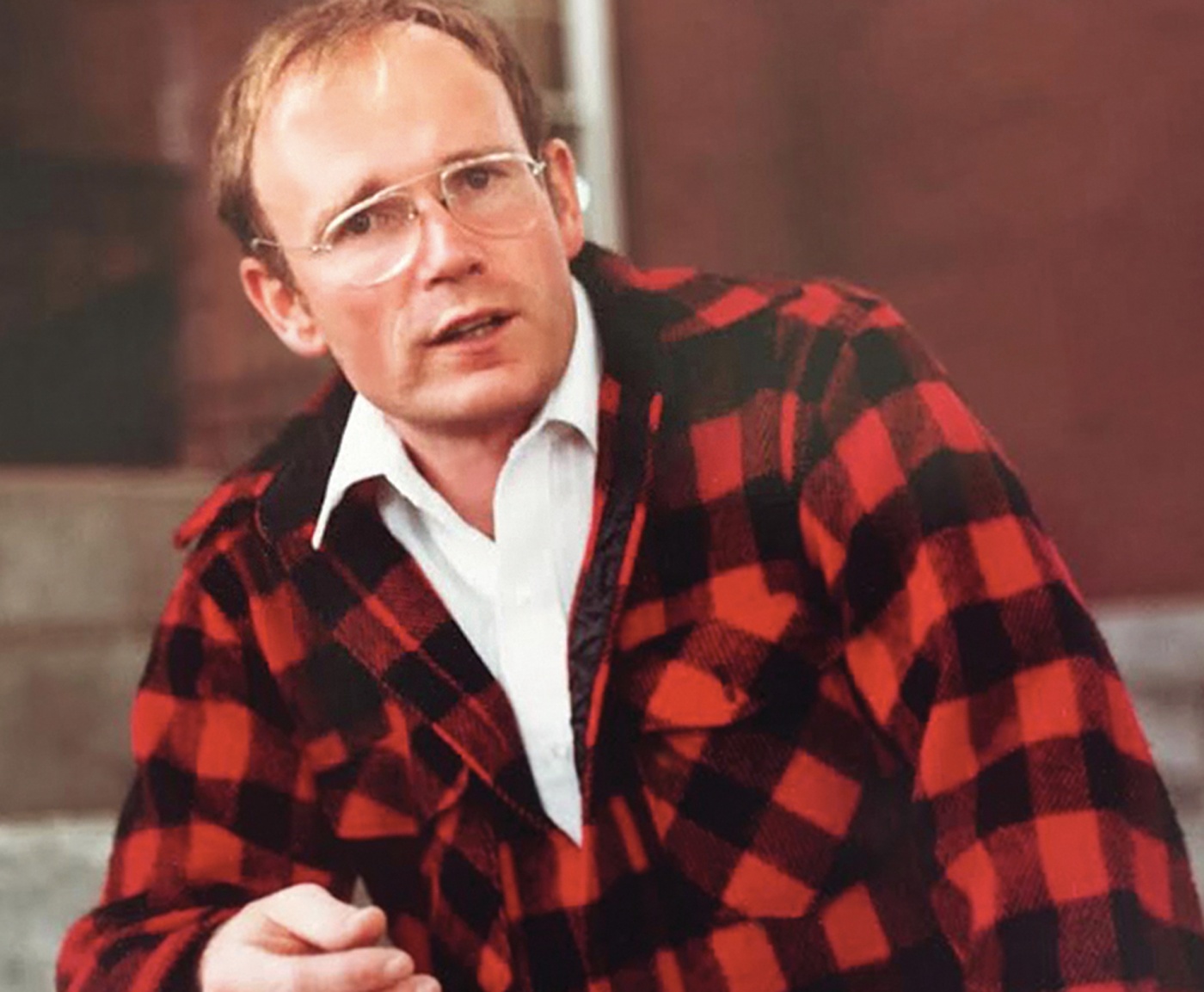

While he described his own skills as “mediocre,” Eastler, a retired Air Force colonel and beloved professor of geology at the University of Maine–Farmington, went on to share his passion as a mentor and coach to several generations of high school racewalkers, including his children. Two of them, Gretchen and Kevin, went to the Olympic racewalking trials; Kevin competed in the Olympics twice and set a number of national records.

Gretchen Eastler Fishman remembers her father waking her at 4:30 a.m. to train before school. “I started competing in racewalking nationally at 14,” she says. “Dad and I traveled all over the U.S. for competitions. You could find him showing anyone, anywhere, anytime, how to racewalk.” All three of the Eastler children continue to compete in track events as adults, Gretchen and sister Laura Farkash as marathon runners.

Thanks to Tom Eastler’s unflagging advocacy, Maine is one of only two states to offer racewalking as a high school sport. (The other is New York.) “He was the father of the racewalk” in Maine, “an ambassador for the sport,” said an officer of the state school principals’ association.

Tom Eastler died in August at age 73 from complications of cardiac and kidney disease. His passing elicited praise and memories from those he had coached on the track and taught in the classroom. People remembered him as a jack of all trades: teacher, hands-in-the-dirt farmer, U.S. Track & Field official, cofounder of Farmington’s youth hockey program, and gregarious friend.

By all accounts “Dr. Rock,” as he was known on campus, was a memorable teacher. “His excitement, sense of humor, and epic tales have ingrained in students the differences between casts versus molds, meteor falls versus finds, strike slip versus dip slip faults, and rural versus urban hydrographs,” wrote alumna Skylar Hopkins in a UMF website article at the time of Eastler’s retirement in 2015. “He has advised students in a tiny office crammed with thousands of books, in a diesel-fueled car (license plate: Dr. Rock) and via emails somehow always sent between midnight and 5 a.m.”

A dedicated environmentalist, Eastler served on the Maine Board of Environmental Protection and the Maine Low-level Radioactive Waste Authority. He was a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the Geological Society of America. His career with the U.S. Air Force included active duty service during the Vietnam War and Operations Desert Storm and Desert Shield.

Her father, says Gretchen Fishman, remained engaged in his children’s athletic careers until the end of his life. “He was able to come watch Laura and me in the Maine Coast Marathon last spring,” she says. “He wanted to travel this fall to see us run.”

Tom Eastler was buried on his farm “in the casket he built, in the hole he dug, marked by the boulder he found in the earth he loved,” Fishman says. In addition to his three children, he is survived by his wife of 32 years, Susan, of Farmington, Maine.