In an age of globalization, Jennifer Knight ’89 has done something extraordinary: she’s revived an American manufacturing brand, returned jobs to a small American town—and in the process, come back to the fabric business she grew up in.

Jennifer Knight thought she was finally done with textiles. But somehow, on this frigid morning in early winter 2014, alongside her new business partner, Jacob Harrison Long, she was pulling up in front of a recently closed 19th-century mill in the charmingly frayed creekside village of Stafford Springs, Connecticut, to see about turning it back into a maker of high-end wool fabric. At the time, she had no idea that they would have the three-site facility’s hundreds of machines, some of them dating back nearly eight decades, up and running again before the end of the year. What they pulled off was no less than the reincarnation of a venerable domestic label that had all but died: American Woolen Company.

Until the prior year, the mill had churned out gorgeous wool for Italy’s Loro Piana, a globally famous maker of high-end wool and cashmere fabric and apparel. But amid a recent sale to the luxury giant Louis Vuitton Moët Hennessy, Loro Piana had closed the Connecticut site, concentrating its manufacturing in Europe. Dozens of highly skilled, middle-aged employees in and near Stafford Springs had been let go with generous severances but no idea how to make a living the rest of their working lives.

The factory and its equipment sat empty, with nobody there the day Knight and Long visited save Guy Birkhead, a Brit who’d run the site under Loro Piana. The trio talked in a chilly conference room for hours. “We asked him if he thought we were crazy; if we had a shot at getting people to come back,” says Knight. “And he said he thought we did.”

Birkhead was right. By the time Knight met a few weeks later with the mill’s former controller to crunch out the financial feasibility, excited rumors had shot through the area that the plant might reopen. The day that Knight and Long closed the deal that June, buying the site and all the equipment for what Knight called “a fraction of its worth”—she would not disclose the sale sum or any financials related to the company—they also hired back 35 of Loro Piana’s most skilled workers.

“That was thrilling,” says Knight, “bringing back these employees to do what they knew how to do.”

Machines were dusted off and tuned up, and the plant, 600,000 square feet in all, was making fabric again by the fall. “Those days were frantic but exciting, with endless stuff to do,” Knight recalls. “We had our first Christmas party December 14. I stepped back into the office for a moment and found out that an order of a few hundred thousand dollars had just come in from J. Crew, and when I went back to the party and announced it, the whole floor cheered.”

J. Crew, which in recent years has heavily promoted its men’s and women’s suiting made with wool from top Italian mills, was “gaga that they could put an American mill into the mix,” says Knight. Orders soon followed from Hickey Freeman, Brooks Brothers, Timberland, North Face, Rag and Bone, Billy Reid, Hart Schaffner Marx—plus Northwest Woolen Mills, the Rhode Island company contracted to make the official U.S. Navy pea coat.

And that is the story of how, in an America where the percentage of textiles manufactured domestically has plunged dramatically in recent decades, one of countless closed factories became the country’s only maker of luxury wool suiting fabric—and dozens of locals were put back to work.

“This has been a really significant event for Stafford,” says State Senator Tony Guglielmo, who lives in Stafford. “We’ve been a mill town for a very long time and it was a real down moment when the mill closed, so the reopening has hit us like a bolt of lightning.”

But it’s only part of the story of how a soft-spoken, Southern lesbian debutante turned 1987 Brown grad got pulled back into the business she grew up in—for the third time.

The culture-shock loop

“I’m fourth-generation textiles,” said Knight, 51, on a recent March afternoon over lunch in Manhattan’s Flatiron District, not far from where she lives with her wife, Chiqui Cartagena, an expert on the Latino market who until recently was a senior vice president at Spanish-

language media giant Univision. (Knight spends several days a month in Stafford Springs, more than three hours away by car, in one of three condos that came with the factory purchase.)

Knight was wearing an overcoat and blazer made from American Woolen camel hair, both of which she’d had custom-made, beneath which she wore a Saks baby-blue cashmere sweater and a red-and-blue cotton Orvis scarf. Her blond hair was bobbed and tortoiseshell glasses lay on the table beside her. Her look was classic American preppy wealth but her demeanor was self-

effacing and soft-spoken, with hints of smirking irony.

Knight grew up in the Deep South city of Macon, Georgia, the oldest of four daughters to a homemaker mother and a father who was the CEO of Bibb, the first linen maker to license logos, such as the NFL’s, for sheets. As a child, she was bookish and wanted to be a writer, but her father would also take her along in his convertible when he visited Bibb City, a self-contained “mill village” with its own schools and police force. “Textiles industrialized the South and brought Southerners into the solid working and middle class,” she says.

When Knight was six, Bibb transferred the family to tony Westport, Connecticut. “We were a very conservative Southern Baptist family,” she says, “and my mom felt like a total fish out of water.” A few years later, though, the family moved back to Macon, where Knight, after time in the North, experienced her own culture shock at the tiny private school she was sent to. Come her senior year, her school headmaster took note of her bookish individualism and urged her to apply to Brown.

She did—secretly. When she told her father she got in, he refused to pay for it. “My grandmother, who I really admired, put her hand down on the dinner table and said to him, ‘Roland, if you won’t pay for it, I will.’ So that’s how she shamed him into sending me.”

Once she got there in the fall of 1985, surrounded by Northern secular liberals, she experienced culture shock all over again. “I was intimidated and shy and it took me time to find friends,” she says. She played basketball and ended up double-concentrating in Religious Studies and Women’s Studies, eventually becoming highly active at the Sarah Doyle Women’s Center. “Brown allowed me step out of the very conservative culture I grew up in and look at it from the outside,” she says. “I ended up studying the history of the evangelical church in the U.S.”

She was evolving in another way too—realizing she was gay. The year she did the debutante circuit in Georgia was also the year she revealed as much to her family. “So I was actually coming out in two ways at the same time,” she laughs. But her family did not take it well. “We were Southern Baptist in Macon, Georgia, in the 1980s. They had no experience with the whole thing and were just completely in shock.”

After Brown, she moved to L.A. with a friend and briefly worked in TV, as a writers’ assistant on the sitcoms The Fresh Prince of Bel Air and The Royal Family. On the set of the latter, the star, the legendary Redd Foxx—who had often hilariously faked a heart attack on his prior show, Sanford and Son—had an actual heart attack and died in front of the entire set. With that, says Knight, “I was out of a job.” Her heart, she adds, also wasn’t entirely set on the Hollywood life.

That’s how she got called back to textiles the first time. Her father had since bought some smaller textile companies in Georgia but was also not in great health and urged her to come home to run things with him. “He said, ‘I’ve got four girls and you’re the only one with a head for business.’ And I had a girlfriend in New York at the time so I wanted to get back East anyway.” She struck a deal with her father that she would split her time between New York, site of the company’s sales and marketing office, and the mills in Georgia.

There was another reason she went home, too. “After I came out as gay, I hadn’t been close to my family for a long time,” she says. “And here was a chance to be close to my dad again.”

Back in rural Georgia, overseeing a company that made the elastic for underwear, she was sometimes bored. “I was going between the factory floor in Georgia and working with garmentos”—Big Apple-speak for longtime rag-biz fellas—“in New York. It felt like a sitcom sometimes. I had to learn our knitting and weaving so I could buy nylon, polyester, and cotton from suppliers all over the world. And I had to relate to folks on the factory floors. We were very good at what we did,” she adds proudly. “We took this little run-down manufacturer and turned it into a high-end, award-winning supplier to top U.S. brands like Maidenform, Hanes, Fruit of the Loom, Victoria’s Secret, and DKNY.”

She had moments of profound satisfaction. “I loved the feeling of it being like an orchestra where everything goes perfectly. And a lot of that comes from the culture you create. We made it clear we wouldn’t tolerate any sort of racial or gender discrimination.” She remembers the time she and her father appointed an older black woman to oversee a unit of about 25 mostly white women. “They all came storming in my father’s office saying, ‘We’re not willing to report to Hazel,’ and my dad said, ‘Then we’re not willing to keep you employed here. Hazel’s the best one for the job.’ And those women accepted it and stayed.”

She also saw a side of America unobserved by her Brown friends, all of whom, she says, had moved to New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, or Seattle. “I really got to understand what it’s like to be in a small town where a couple factories are the entire economic livelihood,” she says. “And yet the writing’s on the wall with offshoring. Brown friends would say, ‘We don’t need those kind of jobs in this country anymore,’ and I would say, ‘But what are these people going to do for work? Nobody’s got a Plan B.’”

Her family sold the business in 2000 to two private equity companies. “I never thought I’d have anything to do with textiles again,” she says. She got her MBA at Columbia, bought some land, and looked into property development on an island off Florida. But a few years later, the private equity folks offered to hire her back to help run the company. “I said yes. I had a fondness for the staff.” Yet her return couldn’t galvanize the business. “We managed to reduce costs, yes, but all our customers were telling us to move offshore, to Central America where their cut-and-sew facilities were, to make the whole supply chain easier for them.”

In 2006, she merged the company with its largest competitor, became president of the new entity and, bowing to the pressures of the times, moved part of the business to Honduras and China. But amid the financial crisis, she says, the equity fund backing them tanked and they sold the company’s assets to another investment group. Once again, she thought her textile days were done.

Once again, she was wrong. A few years later, while working out of Miami for a company staffed by former CEOs who consulted for midsize businesses, she was put in touch with Long, a hyperkinetic Chicago-born investment banker who’d worked years for big banks in Europe. There, he’d become enamored of the Italian art of fine wool-making, for which the country distinguished itself after WWII. He had recently bought the long-unused trademark for American Woolen, a company dating back to 1899, and dreamed of reviving it as an American woolmaker fine enough to compete with Italy. But he needed someone with a textiles background to go forward with. So the two met for coffee in Miami.

“He asked me, ‘Do you think I’m crazy?’ Knight recalls. “And I said, ‘Yes—but your timing might be right because America’s gone about as far with outsourcing as we can and maybe it’s time we tried to do the European thing of making fabric that’s super high-end.”

A mill revived

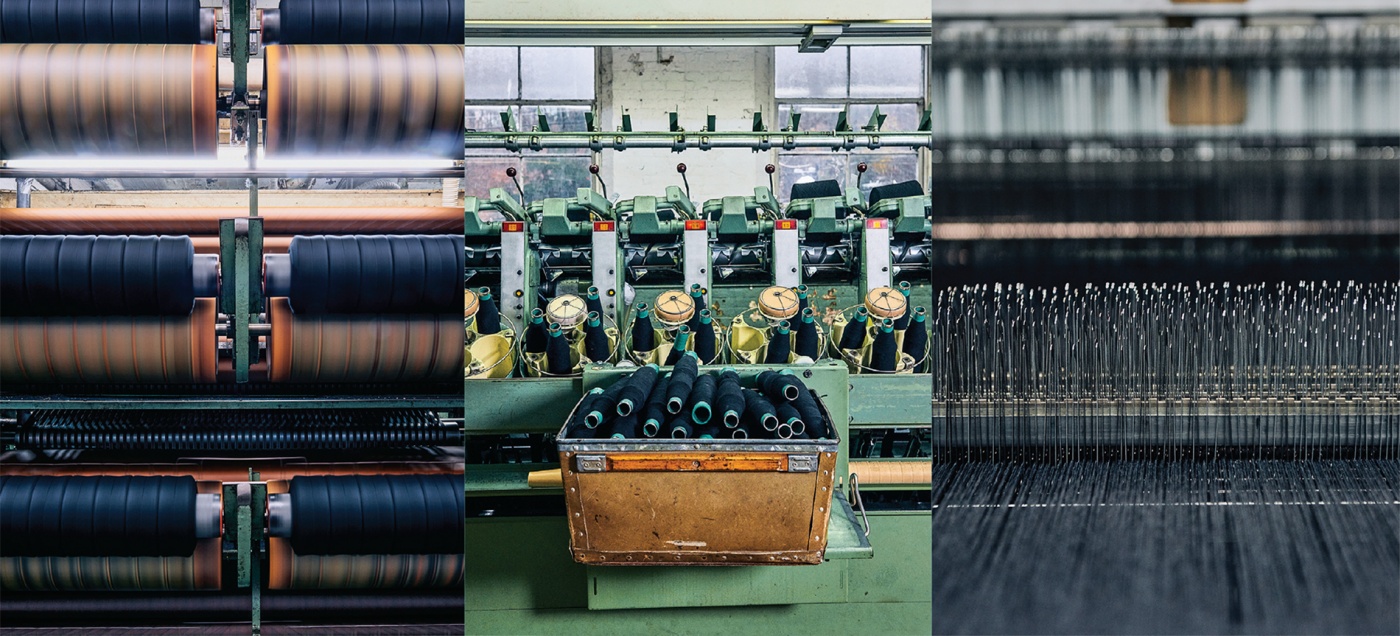

That first meeting evolved into several, leading to the fateful winter 2014 visit to Stafford Springs, the sale, and everything since. On a snowy Friday afternoon last March, while Knight conducted business in New York, Long led a tour through the plant’s three cavernous facilities. Room after room revealed massive equipment, spanning from 1930s- and 1940s-era combers and carders of raw wool to newer, intricate lattice-like machines that spin yarn from endless small bobbins onto bigger cones. Then there were the actual, computer-guided looms, from which beautiful striped and plaid suiting fabrics emerged. Finally, machines wet-finished, dry-finished, and sheared the fabric into voluminous bolts that ran through yet more racks where they would be inspected, inch by inch, for even the tiniest imperfections.

“I learned this whole process from books,” boasted the bespectacled Long, who moved at a dizzying pace and, in his snugly fitted, short-hemmed suit of his own wool, looked much like the stylish European banker he had once been.

Along the way, he stopped to chat about work or home life with many of the employees whom he and Knight had coaxed back to the mill. One such returnee, reached on the phone a few days later, was Giuseppe Monteleone, 55, whom Loro Piana had brought from Italy to Connecticut with them in 1988, then brought back to Italy when they closed the mill in 2013. He’d left behind in Connecticut his wife and daughters so the girls could finish school, hence he had a strong incentive to say yes when Long and Knight reached out across the sea asking him to return as director of operations.

“I had a good salary with Loro Piana,” he said, “but I felt like I had an obligation to come back because I’d been here so long.” He knew not only how every piece of equipment, nearly all of it European, worked, but which servicers to reach out to overseas for updates and repairs. “And coming back was unbelievable, almost like going back in time to 1988 when Loro Piana came,” he said. “But restarting to make a very unique product was a big challenge. I was scared, to be honest.”

Piping in at that moment on the call was Mike Fournier, 53, the CFO, who had not worked at the mill under Loro Piana since 2004 but whom Knight and Long had tracked down. They persuaded him to leave his job as a construction company controller and join the American Woolen team.

“It was definitely like a big reunion,” he says of hiring back, batch by batch, local folks, some of whom he’d not seen in over a decade. “It’s very strange. I’d been gone a long time, but if I ever talked about the mill, I’d say ‘we.’ It was a family here and it doesn’t leave you.”

The process hasn’t been easy, notes Knight and everyone involved. As a textile maker, Loro Piana was its own wool source and its own client, going on to sell the textile to various high-end apparel makers. The new company must source its wool from nations worldwide depending on who has the best quality at a given time, and produces output in an uneven flow based on orders from multiple clients. “The steadier the flow, the easier everything is, and we’re not totally steady yet,” says Fournier. “But we’re getting there. At first we were reaching out for buyers, but now they’re coming to us.”

Among those new buyers is the U.S. military, which late in 2018 put in its first order of wool for uniforms—including a revival of the Eisenhower-era Army “pinks and greens,” which includes a smartly fitted four-button, high-lapel jacket. “I was just on the Hill,” Knight says, “talking about the importance of American apparel companies maintaining a healthy domestic supply chain.” That means when everything, from raw wools and cottons to finished, retail-ready apparel, is made in the USA.

It may sound crazy in this age of extreme globalization, but Knight feels she’s playing a small role in bringing back an age reminiscent of the one she grew up in, walking the factory floor with her father and greeting each worker by name, asking about not only their work but their family.

She pauses a moment to reflect. “At a certain point,” she says, “I didn’t think there was a way for me to stay in this industry because it seemed like it was dying in America. To the extent that you should feel a sense of purpose in life, I have that again. Even on a small scale, we’re creating solid jobs in Connecticut. And we’re making a beautiful product at the same time.”