The 0.3 Percent

Veterans make up a tiny portion of the Brown population—but thanks to recent efforts, more and more post-military undergrads are busting stereotypes and bringing diverse backgrounds to campus.

Michael Muir ’20 could not believe his eyes.

It was November 2016—the middle of his first semester at Brown. He’d come a long, long way to get here. But what was happening on the College Green was not okay with him.

Muir had grown up intermittently homeless and in poverty in the Midwest, then for many years in foster care and group homes. Despite that, he’d excelled in high school, earning a full ride to the University of Wisconsin.

A semester in at Wisconsin, though, he’d realized he was bored. “I was looking for a sense of adventure,” says Muir, 27, whose voice is full of earnestness and intensity. “I’d always wanted to go to California.”

So at 20 he joined the Marine Corps. He was stationed at Camp Pendleton in San Diego for the next four years, becoming a combat engineer with a specialty in searching for IEDs (improvised explosive devices) in combat zones. He did a tour around the world. “I refined skills in the military that I already possessed naturally,” he says, “like how to be a good leader, to recognize skills in others and bring them out. And obviously I learned discipline and maintaining a professional bearing when things are difficult. Having been a Marine is one of the proudest things I have ever accomplished. It gave me a family and a sense of purpose.”

But by 2014, urged by his girlfriend (now his wife), he decided to leave the military to pursue a degree again. He stumbled across Service to School, an organization that helps veterans get into the best colleges possible, and ended up applying, and being admitted to, a slew of elite East Coast schools, including Georgetown, Tufts, the University of Chicago, Cornell—and Brown.

Muir chose Brown mainly, he says, because the school’s then–director of the Office of Student Veterans and Commissioning Programs, Karen McNeil, a Navy vet and Arabic linguist, went out of her way to court him (she recently left Brown to pursue a PhD in Arabic). McNeil left a lasting impression on Muir: “She said to me, ‘We want you here,’” Muir recalls. “When I visited, she cleared her schedule and walked me around campus, took me to lunch. None of the other schools even had [to his knowledge] a military liaison. I thought, ‘If I come here, I can get a world-class education and attract even more veterans to come.’”

So he did just that, funding most of his tuition with the Post 9/11 G.I. Bill, the Yellow Ribbon Program (a federal program that supplements the G.I. Bill) and a gift from Brown. He moved to Providence with his girlfriend, bought a house, and started classes.

And then came the day before Veterans Day 2016, which also happened to be the day after Donald Trump won the election. Muir was helping another member of Brown’s tiny population of student veterans—there are currently 17—plant small American flags on the green for the school’s annual ceremony to commemorate the holiday. “No sooner had we planted them,” he recalls, “then we turned around and students are ripping up the flags, breaking them in half, and stomping on them. When we told them we were veterans, one said that veterans were too stupid to go to Brown. Another said that our presence on campus made them feel unsafe.”

The irony, he says, is that military friends had discouraged him from coming to Brown for this reason. “They said to me, ‘It’s full of crazy snowflakes. Don’t drink the Kool-Aid.’ I had always thought I was liberal. And then I experienced everything that people told me might happen here.”

Open-minded students

Let’s get one thing straight right off the bat: All military students spoken to for this story said that the flag incident was the extreme exception, not the rule, to how they’ve been treated at Brown. “I’ve had great interactions,” says Muir, who is double-concentrating in environmental studies and business, entrepreneurship, and organizations (BEO) and thinks he might want to get an MBA after Brown and get involved in the commercialization of space (as in outer space). “Students have been very open to asking me questions, inviting me to coffee and wanting to learn more about my experiences.”

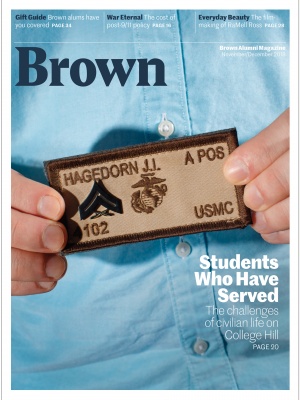

Jonathan Hagedorn ’19, a former U.S. Marine combat engineer in Afghanistan, told the BAM in 2016 that the flag incident was more complicated than was reflected in reporting at the time. “The majority of students thought the flags had to do with the election,” he explained. “It was just bad timing.” When veterans explained why the flags were there, Hagedorn says, most of the flag vandalizers apologized: “A lot of people immediately expressed remorse.”

Aimee Chartier ’21, a 27-year-old poli sci concentrator and Marines vet, says she and her husband, Marines vet and environmental science concentrator Joel Fudge ’21, have also had largely positive interactions. “With the exception of one student who asked me if I sympathized with the Nazis—because they were also ‘just following orders’—students here have been interested to talk to us,” she says, “and see what the military is actually all about.”

But the flag incident still underscores what can feel like an extreme cultural gulf on campus between current or former service members, who tend to come from non-wealthy backgrounds, and the rest of the student body at one of the most liberal, elite schools in the U.S. In addition to the extremely low percentage of veterans on campus, for many years Brown banned military commissioning programs like ROTC. The University changed its policy only after the military dropped its near-two-decade “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy—which discriminated against gay, lesbian, and bisexual service members—in 2011. Prior to that, Brown students had to do ROTC or other military programs at nearby schools, including Providence College, which Brown now partners with for ROTC.

Acknowledging it needed to do better when it came to enrolling both former and active service members, Brown started its Office of Student Veterans and Commissioning Programs in 2012, now helmed by former Air Force intelligence analyst Kimberly Millette, who says her top priorities are growing the number of veteran and ROTC students on campus and making sure they feel welcomed. Former director McNeil worked overtime to convince military students facing an array of top school options to pick Brown. Those above the typical 18-21 undergraduate age were also helped by Brown’s Resumed Undergraduate Education program (RUE), designed specifically for undergraduate applicants who have been out of high school for six years or more.

Upon McNeil’s departure, she had gains to show: her first year at Brown, there was one incoming undergrad first-year veteran; summer 2017, there were six. This year, there are a total of 17 undergraduate veterans enrolled, plus 32 self-identified vets in graduate and medical school.

“It’s important to keep increasing the number of vets at Brown because they’re so underrepresented,” said McNeil, noting that vets make up three to five percent of undergrads at neighboring schools and one percent at private universities overall, versus three-tenths of a percent at Brown. “Lots of vets are going back to school now, but not coming to places like Brown. There’s some kind of inequity going on.”

Plus, she said, “You can make a patriotic argument that we owe something to people who have served their country. And vets bring to campus not only demographic but experiential diversity, which hugely lends to the collective knowledge of their classmates. People assume that vets are always conservative, but Pew research shows that currently enlisted service members mirror the political views of America as a whole. Meanwhile, Brown’s environment does not—it’s significantly to the left.”

Special resources

To help vets at Brown, McNeil organized special orientations, welcome brunches, and one-on-one sessions, with a focus on financial aid. “That’s very different for them,” she said. “Their parents aren’t paying, they’re living off campus, and they’re at a very different place in their lives.”

Then, said McNeil, there’s mental health. “That’s a need for all college students but veterans have different issues and post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD] is sometimes one of them.” Among staff at Brown’s Counseling and Psychological Services, she notes, is Jamal Pollock, who previously worked as a counselor at Veterans Affairs in Harlem. “So we have great resources,” she says. She also alerts professors that they have vets in their class—but she also urges them not to assume that all vets have been in combat or have PTSD.

However, such was the case with Hagedorn, 26, a biology and theater double concentrator who served seven months in Afghanistan in 2013 in the Marines, searching for IEDs in the road. “Most of my friends got blown up during that deployment,” one fatally, he says, “and I was lucky that my truck did not.”

But upon staying with his sister in New York City post-Marines and pre-Brown, he felt assaulted by “the huge crowds, unexpected scary noises, and lots of bangs. I had a lot of breakdowns and wasn’t sure what I was dealing with. It snuck up on me. My deployment wasn’t as bad as many people’s, so I was like, ‘I’m fine, I can’t claim to be damaged.’”

He saw therapists. “It was all about learning specific coping tools for hardcore panic attacks and bringing yourself back to earth when you’re losing a grip,” he says. “I tended more to have emotional attacks—I’d start weeping uncontrollably on the subway. I’d say right now is the best I’ve been. I’ve gone through a lot of different medications but now I’m on a constant treatment plan and it’s going well. I do yoga, meditation—a little bit of everything.” PTSD, he says, “isn’t something that leaves you. You just kind of learn to live with it.”

Amid those struggles, he calls Brown “paradise. My worst day here is better than many of my best days in the Marines, where leadership abused me and my platoon for over a year. Going from that to here, I’m so grateful. I mesh well with the liberal arts kids here.” He also does theater and says that after Brown he wants to go into some kind of storytelling or media education. “I haven’t felt hostility toward veterans here. This is a place of thoughtfulness and understanding, and the stereotype of it being full of special snowflakes is just wrong. But they do work hard here to make sure everyone who has suffered and has a story to tell feels safe doing so.”

Unregimented life

“I came into Brown wanting to be a neuroscientist,” continues Hagedorn, “because there was a guy in my military company who got blown up so many times that now, every time he laughs, he passes out. A lot of my military friends have traumatic brain injuries.”

Similarly, Nicole Dusang ’20 PhD, who is 40, says that she is studying electrical engineering mainly because, during the multiple deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan of her 11 years in the Air Force, where she was an explosive ordnance disposal officer (“It was a blast,” she deadpans), she became fascinated with “assistive technology,” such as smart limbs, for veterans who had been injured.

“I’m obsessed with how we can interface with the brain and use different types of engineering therapies to help alleviate some of these issues. Brown is one of the premier institutions for brain-computer interfaces.” It was her only choice for a PhD program. “If I didn’t get in I don’t know what I’d have done—I didn’t apply anywhere else.”

The atmosphere on campus is exhilaratingly open and fluid, says Dusang, who commutes daily from Norton, Mass., where she lives with her husband, Steve Coddington, whom she met when they were both serving in Afghanistan and who also is enrolled at Brown in the Executive Master Program for science and technology. “The military is incredibly regimented and gives you very directed training, but here I can literally take any class I want, which is overwhelming at first, but I’ve gotten used to it. Last week I participated in a conference exploring women’s roles in facilitating peace and providing security. I’m not sure I would have these types of experiences anywhere else.”

Chartier feels similarly. “I learned discipline and time management in the military, which is a good skill to have to get your work done in college,” she says. “But here, you’re allowed to explore your own path. I can basically do whatever I want here.” Chartier, who wants to work for the Department of Defense after graduation, says she thinks that both faculty and students gain a lot from having veterans in the mix on campus.

“They were talking about the 2011 Japan earthquake in one of my husband’s classes,” she says, “and he had served on a humanitarian disaster-relief mission there after the crisis. The professor really appreciated that input. Brown always touts diversity, and I don’t think you are going to find a much more diverse group here than the vets.”

Vets helping vets

Last year saw the launch of the Brown University Veterans Alumni Council, started by Joseph Santarlasci ’67, a Vietnam vet, and Larry Eichler, the father of David ’09 and Dan, a Georgetown grad who is now a second lieutenant in the Air Force. Eichler, a Providence attorney, said that, once Dan joined the military, he realized that vets studying at Brown must face special challenges.

“I thought they really should have some mentorship program,” he says, “something to try to connect this whole group of Brown students or alums who are veterans.” Hence, BUVAC was born, pairing military students with mentors who are both Brown alums and current or former service members.

For example, Manuel Villagrán ’19.5, age 26, a public policy concentrator and Arabic scholar who spent three years stateside in the Army before coming to Brown, has as his mentor Jonathan Hillman ’09, age 31, who transferred to Brown after three years at the West Point military academy. “We’ve talked together about my future and what I want to do, whether it’s grad school or a job,” says Villagrán. “This is a brand-new journey for me—no one in my family has ever gone to college.”

He strongly urges other vets to apply to Brown. “I never expected that such a prestigious school would look at my military record and say, ‘This guy would be a great fit here.’ It was a fantasy to me. It was professors from my community college in California who insisted I apply.”

And James “Jimmy” Fox ’19, 32, a Navy vet who served in Japan and now a BEO concentrator, has as his mentor Scott Quigley ’05, who did ROTC while majoring in poli sci at Brown before serving in the Army for seven years, including as the “mayor” of a district of Baghdad during the surge of 2007. Quigley then returned to get two master’s degrees at Harvard and then go into private equity in Boston.

“I’ve always said that I wanted to be helpful to people who’ve served who want to go to college,” says Quigley. “Jimmy and all the vets at Brown are in a unique situation, so I give him perspective and context and will help him navigate the finance world he wants to go into.”

Fox says that he loves the intellectual excellence at Brown—“I have 18-year-olds here tutoring me in calculus,” he laughs—but admits that, living off campus with his fiancée, he isn’t very much a part of student life. “It’s more like getting in my car and going to work and coming home,” he says.

As for Muir, the former Marine who planted the flags on the green, he’s more than found his groove. The summer of 2018 found him internship- and conference-hopping all over the country, from HBO in New York City and Google in Mountain View, California, to consulting giants Deloitte in Texas and Bain in Boston. He says that Brown has opened up a world of possibilities for him.

And as for that flag incident? He says it taught him to do what so many other Brown students have done—agitate. He wrote an op-ed for the Brown Daily Herald and went on a local radio station demanding respect for the campus’s tiny veteran population. He successfully urged Brown President Christina Paxson to issue a denunciation of the flag-ripping. He and other vets also got Paxson and Provost Richard M. Locke to sit down with them, to commit to recruiting more vets to Brown—and even to give the vets their own lounge in a building on George Street.

“I decided that day that I wouldn’t just be a victim,” Muir remembers. “And a lot of good things have stemmed from that incident. Something I really like about Brown is that undergrads here have a tremendous amount of power. You just have to make a big stink and things get done.”