When American troops invaded a strategically located nation halfway around the world, supporters hailed it as a blow for the freedom of an oppressed people. And so the nation was shocked when full-scale insurrection arose just a year later. One baffled newspaper called the rebellion “the insane attack of these people on their liberators.”

Kinzer—a veteran foreign correspondent who’s now a senior fellow at the Watson Institute—does a remarkable job of showing how the debates over U.S. global might and imperialism that exploded into view during the Vietnam War and that were rekindled during recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan are nothing new. In fact, they can be traced back to the turn of the twentieth century, when Americans were torn apart over whether foreign conquest was a logical outgrowth of the emergence of the United States as a powerhouse of the Industrial Revolution. In many ways The True Flag brings the career of Kinzer—who first made a name for himself covering U.S. meddling in Nicaragua for the New York Times during the 1980s—back full circle on the central question of whether or not America’s foreign policy is a force for good in the world.

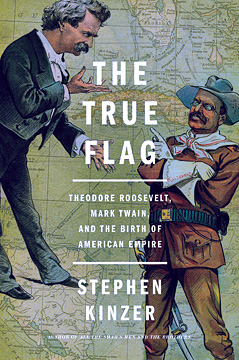

Those questions were no easier to answer in 1898 than they are today. Roosevelt—brilliant yet oddly buffoonish in his pursuit of machismo as leader of the so-called “Rough Riders” in the Cuban conflict—had powerful pro-imperialism allies in the wonkish Senator Henry Cabot Lodge and the yellow journalist William Randolph Hearst. Although their emotional, flag-waving jingoism was an almost irresistible force, an unlikely band of anti-imperialist allies, from the industrialist Andrew Carnegie to the populist William Jennings Bryan, still managed to make a case against interventionism that persists in the American zeitgeist to this day.

Writing in a crisp, fast-moving journalistic style, Kinzer recaptures the exact moment when Americans’ ideas about our place in the world were very much up for grabs. One oddity is that Twain, despite his top billing, seems to enter the story surprisingly late, too late for his sharp denunciations of the U.S. occupation in the Philippines to have much real impact.

Still, many readers, knowing how the next hundred years would play out, will find little to disagree with in Kinzer’s argument against the naive “illusion” that “America’s inherent benevolence … made it unlike any previous great power.”