In a New Orleans courtroom one morning last November a team of corporate attorneys appeared before a judge to ask that she dismiss a lawsuit that could cost their clients billions of dollars. The lawyers represented almost 100 oil and gas companies, including such giants as Chevron and ExxonMobil. The plaintiff was the board of the public Southeast Louisiana Flood Protection Authority–East. It had asked U.S. District Court Judge Nannette Jolivette Brown to hold the oil and gas industry partially responsible for the disappearance of huge swaths of Louisiana’s coastal wetlands, which have historically been buffers against such violent storms as Hurricane Katrina. The flood protection authority wanted the judge to require the companies to help pay the estimated $50 billion dollar cost of restoring those wetlands, or else pay to construct other flood-protection structures in their place. It was, the New York Times had declared, “the most ambitious environmental lawsuit ever.”

Barry started running into trouble back in 2007. He’d just been

appointed to a new regional levee authority established

post-Katrina to ensure that the people overseeing the area’s

environmental defenses against future hurricanes were technical experts

instead of political insiders. As Barry grew increasingly frustrated by

the lack of money available to pay for Louisiana’s grand plan to

rebuild the wetlands that once absorbed the worst Gulf of Mexico tidal

surges, he realized that a drastic solution was needed. So in 2013, as

vice chair of the flood protection authority, he convinced his

colleagues to file suit against the oil and gas industry.

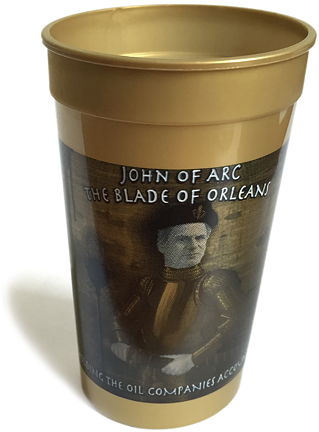

It was an audacious move that made him an instant folk hero to those

who’d long felt that the powerful, lightly regulated industry had

earned huge profits while degrading the environment. But the move also

turned Barry into a lightning rod for those who viewed the industry as

a major supplier of good jobs and state revenue that had done

everything the government asked.

Many, including Jindal, believed that, by filing the lawsuit, the levee board had abused its power and exceeded its legal authority. “We’re not going to allow a single levee board that has been hijacked by a group of trial lawyers to determine flood protection, coastal restoration, and economic repercussions for the entire state of Louisiana,” Jindal said. When Barry’s appointment on the flood authority was up for renewal, Jindal refused to give him another term.

This change in status did nothing to weaken Barry’s resolve. To him, the issue is simple. State regulators, he believes, have failed to enforce the oil and gas companies’ permit obligations to repair whatever damage they cause. “The message to these companies” in the lawsuit, Barry says, “is ‘Keep your word, obey the law, and take responsibility for your actions.’”

The oil and gas industry has been drilling in Louisiana’s coastal zone since the early 1900s, and today a majority of domestic offshore oil and gas comes from the state. In addition, much imported oil is delivered there. Over the decades, the industry has built thousands of miles of canals and pipelines in Louisiana to move all this petroleum. According to the flood protection authority’s lawsuit, thanks to this “mercilessly efficient, continuously expanding system of ecological destruction that injects seawater, which contains corrosively high levels of salt, into interior coastal lands, killing vegetation and carrying away mountains of soil,” the industry “has ravaged Louisiana’s coastal landscape.” The U.S. Geological Survey estimates that, since the 1930s, Louisiana has lost about 1,900 square miles of its shoreline. All its wetlands could be gone within 200 years. The U.S. Department of the Interior estimates that oil and gas development has been responsible for anywhere between 30 and 59 percent of that loss. (The industry has put the figure at around 36 percent.)

In a state as heavily dependent on oil and gas jobs as Louisiana, asking the industry for billions of dollars, as the lawsuit in effect does, is bound to raise alarms. The industry estimates that in fiscal year 2013 it paid about $1.5 billion in Louisiana state taxes, which represents almost 15 percent of taxes collected. About 65,000 people work for oil and gas companies in the state, and the industry claims it generates about $20 billion a year, directly or indirectly, in Louisiana household income. Not surprisingly, oil and gas industry lobbyists play a prominent role in the state and contribute readily to political campaigns. Last year, for example, a consortium of Louisiana environmental groups estimated that Jindal had received over $1 million in campaign contributions from the oil and gas industry over the previous decade. No wonder few elected officials endorsed Barry’s crusade.

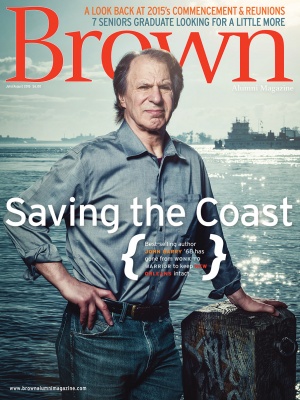

Until 2007, Barry was known as the author of a half dozen sweeping,

meticulously detailed, award-winning history books. His most recent, Roger Williams and the Creation of the American Soul

explores the fundamental relationship between church and state in

America. Because it was published in the middle of the 2012

presidential election cycle, it offered useful background for an issue

that was often discussed. His 2004 best-selling The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History,

chronicled the 1918 pandemic, and it came out just as the outbreak of

bird flu ignited new fears of a global health emergency.

Soon Barry was consulting with public-health officials and publishing

articles in general-interest and scientific publications. The book led

to commencement speeches at the Johns Hopkins and Tulane schools of

public health and landed him an academic appointment at Tulane, where

he keeps an office and is both a distinguished scholar at the Center

for Bioenvironmental Research and an adjunct faculty member at the

School of Public Health. “I discovered that I knew something that was

of value,” he says, and “that people who are experts in the field

accept it.”

It was Rising Tide that made him a household name in his adopted home town of New Orleans. The book focuses on the most destructive river flood in U.S. history, the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927. Although the flood was little known—Barry says he first came across it when he read a fiftieth-anniversary account in a local paper during an earlier stint in New Orleans coaching football at Tulane—it changed the way the country managed water. So vast was the destruction, in fact, that it eventually prompted the Corps to design and build the system of levees and floodways that still seeks to tame the lower Mississippi. The aftermath also upended outdated social structures and racial codes in Louisiana, helped elect Huey Long governor of Louisiana and Herbert Hoover president of the United States, and provided fuel for the great African American migration north.

Rising Tide earned the Society of American Historians’ Francis Parkman Prize as the year’s best book of American history. Its details resonated in particular among those who still live with the flood’s aftermath, which includes questionable water management decisions by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and widespread corruption among levee authorities. The story of how New Orleans elders dynamited a downstream levee to save a wealthy part of the city came back in urban legend form after Katrina struck some of the same poor areas and flooded them. The authorities sacrificed their neighborhoods once, the conspiracy theorists reasoned, why wouldn’t they do it again?

A recent article of faith in Louisiana is that one reason at least some of New Orleans’s flood-control levees had not held up against Hurricane Katrina was the incompetence, balkanization, and long history of political corruption among local levee authorities. A citizen-driven reform drive sprung up, and the state constitution was amended in 2007 to create several regional flood authorities, which were meant to depoliticize, centralize, and professionalize flood-protection oversight. Using a list provided by a blue-ribbon panel, then-Governor Kathleen Blanco appointed engineers, accountants, and attorneys to the authorities. She also chose Barry, who brought his familiarity with the Corps, his policy gravitas, and a touch of star power.

Respected as it was, though, the board had no tools to deal with its main challenge: finding the money either to fund the state’s rebuilding of its vanishing coast or to build higher levees to compensate for the buffering wetlands once provided. After the lawsuit was filed against oil and gas companies, the reaction was immediate and brutal. This is a state, after all, which is so tied to the oil and gas industry that even the catastrophic 2010 BP oil spill fifty miles off the coast did little to weaken the relationship.

“You expected there to be blowback,” says Gladstone Jones, the

attorney who ultimately took on the case. “What we did not expect was a

hurricane level six.”

One of those most outraged by the authority’s lawsuit was Jindal, who

quickly called for its withdrawal. Not only would he eventually use his

appointment power to replace Barry and some of his allies on the

authority, his new appointments would all be lawsuit opponents.

Jindal’s top coastal aide, Garret Graves, who has since been elected to

Congress, went so far as to call opposition to the suit a “litmus test”

for appointment.

Once removed, however, Barry joined with environmental groups to form a nonprofit that would keep on pushing. In his own mind, Barry was not acting as a bomb-thrower when he filed the suit. “I’m not sure I consider myself an activist,” he says. “I got into this and increasingly became active.” He believes he was acting as a responsible official. After all, he had the unanimous support of the authority. Why shouldn’t the oil and gas companies pay their fair share for their role in wetland losses? And even if the lawsuit failed, Barry reasoned, perhaps its pressure would bring the companies to the bargaining table for a negotiated settlement. As Jones put it, “He’s a very diligent researcher. He wouldn’t set a fire half-assed.”

Barry was heartened that the state Democratic Party endorsed the suit, but with Democrats out of favor in the state, few voiced public support. U.S. Senator Mary Landrieu, who had been recently appointed chair of the Senate Energy Committee and was playing up her ties to the industry in her 2014 reelection campaign, first said she wanted to see the lawsuit play out, but later pulled back. It was easier for those who were safely retired to support action. Speaking at a joint forum at Loyola University in New Orleans several months after the suit was filed in 2013, three former governors, Republican Buddy Roemer and Democrats Edwin Edwards and Blanco, backed the suit.

“We’ve all known that the channels that were dug and not restored have contributed mightily to our land loss,” said Blanco, who had pushed through the constitutional amendment creating the independent authority. “I would predict that these major companies will come to the table if the lawsuit isn’t destroyed in the political process … and we’ll have a negotiated settlement. I think that they all know that it’s long overdue and that they owe something back to the state of Louisiana.”

During the state legislature’s spring 2014 session, bills were filed to kill the suit and even to restrict the board’s independence. Barry held scores of meetings with legislators, and while he says he often heard supportive words in private, he could see that he was up against a lobbying juggernaut. He says one lawmaker passed him a note letting him know that “they get mad if they even see me talking to you.”

Nevertheless, the lawmakers passed one version, which Jindal signed, saying, “This bill will help stop frivolous lawsuits and create a more fair and predictable legal environment, and I am proud to sign it into law.” However, the issue became moot in February of this year, when Judge Brown rejected the lawsuit, ruling that the Southeast Louisiana Flood Protection Authority–East did not have the legal standing to pursue it. The authority has appealed the decision.

By making the transition from wonk to warrior, Barry has undoubtedly brought national attention to what can happen when one industry dominates a state’s economy, and along the way he has attracted some bipartisan support. Quin Hillyer, a contributing editor to the conservative National Review and a former weekly conservative columnist for the New Orleans Advocate, has been a harsh critic of the flood authority’s legal strategy, but he still finds much to admire in Barry’s single-minded pursuit of the cause. In February he and Barry published an opinion piece emphasizing their points of agreement, including the energy industry’s role in causing significant damage and the urgency of aggressively combating the losses. They also proposed a fee on industry to finance wetlands projects.

Hillyer says he and Barry hadn’t crossed paths before the lawsuit, but “I’ve been a great fan of his work. Rising Tide was fantastic. Other than this disagreement, I was inclined to like him.” But what struck Hillyer once they got to know one another was that Barry “doesn’t leave well enough alone.” Barry, he says, is “monomaniacally intent on saving and restoring coastal wetlands, which is a tremendously worthy goal, and he is willing to try just about anything to do it. I completely disagree with his legal judgment and some of the tactics he used on the levee board, but I think he is very well-motivated.”

Barry admits he may have been naïve about how quickly and easily things would change in Louisiana, at least among those with political power. “You know,” he says, “I really believed that once we stepped forward someone else would step up. We were a heat shield, but apparently it’s too hot for anybody else. Right now, frankly, I’m more pessimistic than I’ve ever been that we will ever have a successful program to preserve what can be preserved.”

He says he still thinks filing the suit was worthwhile, though. It shifted the conversation, he believes, so that even lawsuit opponents now concede that the oil and gas infrastructure is contributing to the wetland loss that has weakened flood protection. Barry continues to do what he can, offering advice, when asked, to localities filing more limited lawsuits, monitoring bills in the state legislature, and arguing his case to anyone who’ll listen. Asked whether the nonprofit pushing the original suit is still active, he replies, “Well, I’m active.”

But less so. He is beginning the transition back to wonk, although now it’s doubtful he will ever again abandon his impulse as warrior. He has started his next book project, and not surprisingly, its focus has been the developments of the past few years. “I swore when I started this,” he says, “that I was not going to write about it. I purposely didn’t take notes in meetings, to make sure I wouldn’t be tempted.” Now he plans to tackle the environmental plight of the coast from a “pretty broad perspective.”

“It’s not a book about the lawsuit,” he says, “but it will include the lawsuit. It will include all the causes, the dams on the Upper Missouri, navigation interests, obviously pure geology.… The issue is too big, and it’s not being addressed.” Because he is a historian, he says, the book, “doesn’t have an agenda, at least in terms of motivation for doing it. It’s just interesting. I write books that interest me.”

Stephanie Grace is a political columnist for the New Orleans Advocate.