My first glimpse into the world of Egyptian cartooning was as a study-abroad student in 2007. I’d done some illustrating for the Brown Daily Herald and went on to offer my services to the student weekly at the American University in Cairo. The young editor obliged.

The paper’s newsroom looked out on Tahrir Square, the future site of the uprising that would inaugurate the Arab Spring in Egypt. In those days the square was tranquil. When a protest was planned, hordes of plainclothes policemen assembled at the university’s gates, which sat on the square’s periphery. From the newsroom, I could see the banality of a dictator’s daily repression.

Four years later, in 2011, from my desk at Foreign Policy magazine in Washington, D.C., I watched the Arab Spring unfold on television. Thousands of protesters occupied Tahrir Square for eighteen days until Mubarak fell. I wanted to get back to Egypt to witness the transformation firsthand. I wanted to see how cartoonists were reacting to the upheaval.

In 2012, I was able to return to the American University in Cairo as an editor of the Cairo Review of Global Affairs, a new policy journal. I also earned a Fulbright fellowship to research Egyptian caricature.

I quickly discovered that, while cartoonists’ prestige in the United States had withered along with print newspapers, in Egypt cartoons continue to make headlines. There, political cartoons still take on the most vexing issues of the moment. The gags feature naughty Arabic slang. The imagery is dark, irreverent, and so powerful that leaders still quiver in the face of what is a subversive art form.

By buying six local newspapers daily and clipping the comics, I found a new way to look at Egypt’s political impasse. Not surprisingly in the context of the Arab Spring, cartoonists enjoyed a new level of freedom. They routinely lampooned the president and the military. Mubarak, now in prison, was a common punch line.

On a steamy July day in 2013, I was watching TV with Andeel, a twenty-seven-year-old cartoonist. We sat on the couch with his illustrator buddies, cracking jokes in Arabic and waiting for pizza to arrive. Protesters packed Tahrir Square, a fifteen-minute walk from Andeel’s apartment. By the time the doorbell rang, the military had seized power. Then the Fulbright director called and told me to leave the country immediately. I was on the next flight to Istanbul.

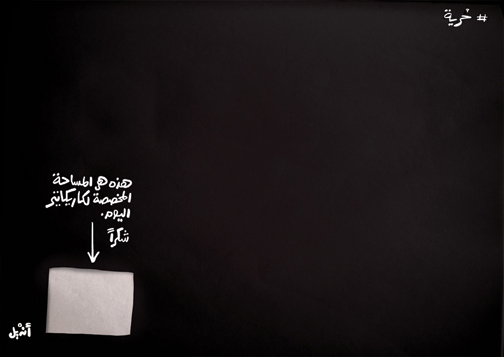

While much of the country was celebrating the military takeover as a second revolution, Andeel harshly caricatured the military from day one. Of his hundreds of cartoons, my favorite was the jab at censorship shown above. A blacked-out frame around a small white box is captioned, “This is the space allowed for today’s cartoon. Thank you.” Andeel titled the cartoon “Freedom.” The authorities were in the midst of a lethal clampdown on the Muslim Brotherhood, and there seemed to be less freedom than at any time in recent memory.

Much has changed over the past four years. The current regime’s suppression of dissent now extends to all opposition voices. Protesting in Tahrir Square is effectively illegal. Journalists are in jail.

But cartoonists are still creating new spaces for resistance. Combing the Egyptian newspapers for new cartoons, I find hope in their audacity. Egypt’s Tahrir Square revolution might be long gone, but the comics revolution continues.

Jonathan Guyer, a senior editor of the Cairo Review of Global Affairs, has written for the Paris Review, the New Yorker, and Guernica.