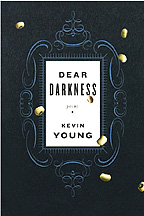

Dear Darkness by Kevin Young '96 MFA.

Reading Dear Darkness, poet Kevin Young's sixth book, I imagined myselfsitting next to the poems' speaker and perusing the family album heholds in his lap. Dedicated to Young's late father and grandmother,these poems are more than static images, though: the poet weaves inhomages to childhood food ("Ode to Pork" and "Ode to Boudin," forinstance) and references to music, giving the poems rich texture andvitality. This book is a sensory map of a family's history and present,its grief and joys, its recipes for how to carry on.

Young, a professor of English and creative writing at Emory University, grew up in Louisiana, and Dear Darknessis imbued with its culture, as experienced by an African American man.Young writes of his father's death, and blood is the subject of many ofthese poems. "Bloodlines" begins with a memory of wild roses and beingcaught smoking by a grandmother:

The roses, wild, along the road

grew white & red & wide—mud-

colored, meddlesome, they

scratched

when kissed, like father's beard.

Little scarred us then. We heard

the rain stop & ran

out to smell the afternoon

after the fall—

Young's sly humor comes out in quick couplets and ragged linebreaks: "Aunties will fix you / a potato salad / & save / yousome," he deadpans. Dear Darknessis divided into five sections, each again subdivided, but almost nopoem exists alone. There's a scattering of odes, a lullaby, an elegy(one of my favorites is the Robert Creeley–esque "Another AutumnElegy"), and blues poems, such as "Slow Drag Blues." Young explores therelationship between the speech of childhood (and family) and that ofadulthood; many of the more narrative poems in this collection turn onthat relationship. "Nineteen Seventy-Five" is told in a voice that isequally comfortable saying "back in the day" and "I cannot recall."

The odes, especially those to food, offer an escape from the tensionbetween the boy (past) and the man (present) as they celebrate thedishes of Young's childhood, the people who made them, and theliterally gut-level pleasure the food still gives. With their slangylanguage and quotes from relatives, the odes are a perfect vehicle forgrief and love. Taste and smell, after all, instantly conjure memory.It's hard to talk in poetry about physical experiences of this kind,but Young does it remarkably well—as in the collection's final "Ode toBoudin":

The heart of you is something

I don't quite get

but don't want to. Even

a fool like me can see

your broken

beauty, the way

out in this world where most

things disappear, driven

into ground, you are ground

already, & like rice

you rise.

Poet Linnea Ogden lives in San Francisco.