Editor’s Note: This BAM coverage of a student strike in May 1970, protesting the Vietnam War, was titled “The Strike: People are getting down to what has been bugging them for a long time.” The article starts by comparing Brown students being dismissed in December 1776 due to the Revolutionary War (George Washington’s famous crossing of the Delaware was about two weeks later) to when the student strike—“virtually endorsed” by the faculty—suspended academic activities in May 1970. Acting President Merton P. Stoltz spoke forcefully in favor of Brown itself maintaining a position of neutrality.

“This is to inform all the Students that their Attendance on College Orders is hereby dispensed with, until the End of the next Spring Vacation; And that they are at Liberty to return Home, or prosecute their Studies elsewhere, as they think proper: And that those who pay as particular Attention to their Studies as these confused Times will admit, shall then be considered in the same Light and Standing as if they had given the usual Attendance here."

The date of that announcement was Dec. 14, 1776, and the College to which it referred was Brown. It may be an invidious comparison to relate the events of 1776 to those which took place here in May, 1970. But when Brown earlier this month suspended its normal academic activities in protest to the Vietnam war, the sense and spirit of what significant numbers of students and faculty were saying were not far from the intent of that announcement nearly two centuries ago. The times had become sufficiently troubled that it was no longer desirable, or perhaps possible, to carry on as usual the business of the University.

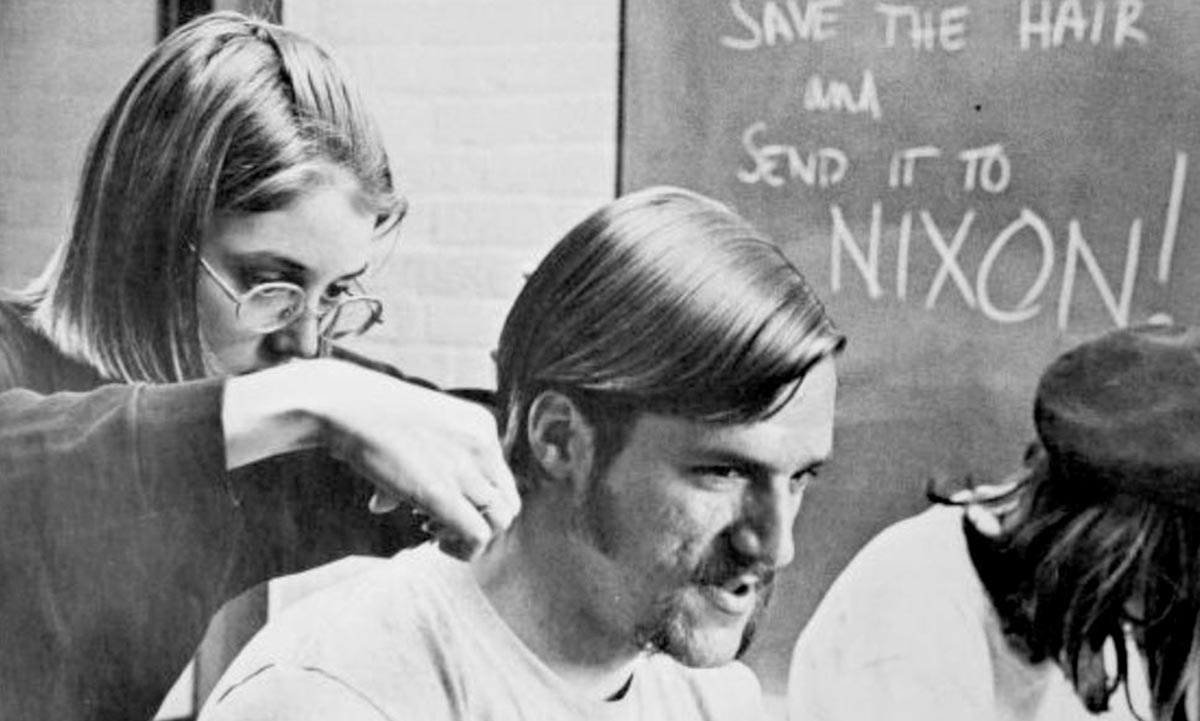

The chronology of events that led a major part of the Brown student body to vote on May 4 for a strike and which led the faculty virtually to endorse that decision the next day is a variation on a theme played at more than 300 U.S. colleges and universities this month. It had been conceded generally that the anti-war movement on the campus was smoldering but not aflame, its ashes fanned periodically by remarks made against protesting students and the educational establishment by members of the Nixon Administration, most notably Vice-President Spiro T. Agnew.

When, on April 30, President Nixon announced that U.S. troops had crossed into Cambodia, the anti-war machine here, as elsewhere, was again in high gear, this time supported by far greater numbers than was the case during the October and November moratoria. The May 4 deaths of four students shot by National Guardsmen on the campus of Kent State University became the instant catalyst that brought into the anti-war movement thousands of previously uncommitted students and adults alike.

To understand what happened at Brown this month, it is necessary to generalize on a number of points which may be disputed by many but which embody the remarkable spirit of large groups of students and faculty in the first 10 days of the strike:

1. The University did not close but remained open, providing an optional arrangement—however well or ineffectively it may have been carried out—for students and others in the Brown community to work in the anti-war movement or to complete their academic work, or both.

2. The strike began with broad support from large and diverse elements of the University community and was not the work of the small minority of "radicals" generally blamed for triggering such action.

3. The strike has been non-violent. At presstime, not a single act of violence, damage, or physical force on the part of students was reported anywhere within the Brown community.

4. The organization of the strike was intentionally loose to reflect its wide and divergent support, and this has spawned an amazing amount of activity, nearly all of it along traditional lines of political dissent. It has seen a weakening, not permanently perhaps, of the mass political demonstration in favor of large numbers of individuals working in their own way to effect a change in U.S foreign policy. The organized confusion and the growing disenchantment with mass rallies tends to confirm James Reston's comments in the May 10 New York Times that university students are beginning to realize that demonstrating, without organizing, is "like kissing the girl and running for home—a pleasant experience with no lasting consequences."

If these really are extraordinary times, as many have said, then Monday, May 4, was the most extraordinary day of all, at least at Brown. Early in the day 16 student

leaders delivered to the University a statement that denounced President Nixon's decision to enter Cambodia and to resume the bombing of North Vietnam, and demanded that the University abandon the position of "neutrality" that Acting President Merton P. Stoltz has consistently maintained is vital to the preservation of Brown as a forum in which all forms of dissent may be expressed. Dr. Stoltz, joining together with the presidents of three other Rhode Island colleges and universities, had wired the state's two senators and two congressmen asking them to return home to meet with student leaders to discuss the war in Southeast Asia only hours before news hit the campus that four students had died in the demonstration at Kent State.

Coincidentally that night, Senator Jacob Javits (R-N.Y.), whose daughter Joy is a senior at Pembroke, had chosen Brown to deliver what he termed a major statement of foreign policy. In that speech before an overflow crowd in Sayles Hall, Senator Javits said the nation was on the brink of a constitutional crisis between the President and the Congress over the war in Southeast Asia. Immediately after the crowd gave Javits a standing ovation, students and others left Sayles for a mass meeting on the Green to decide the issue of a strike.

What happened on the Green will be debated for many months to come. There, between 3,000 and 4,000 students and some from outside the Brown community, came together to debate the issues of a strike. Voices on both sides of the question were heard, generally without the derision that has marked similar meetings on other campuses. The question was limited to whether an indefinite strike should be called in protest of the Vietnam war, and a vote that extended into early morning hours was taken. The announced result: 1,895 in favor of a strike; a reported 884 students dissented against that decision.

Already that night, challenges were made by members of the Young Republicans and other moderate and conservative students for a more controlled vote. The same groups later asserted that the final tabulation was not an accurate expression of sentiment of the student body. The validity of those charges probably never will be established, but it is important to state that no significant opposition voices were heard in the mass meetings that followed in Meehan Auditorium on May 5 and 7. The Young Republicans called a press conference later in the week to say that many students supported President Nixon's Cambodian decision, but none of them spoke at subsequent mass meetings when the strike demands were being expanded and the microphones were open.

On Tuesday, May 5, a student rally was attended by about 1,500 in Meehan. It again called for immediate withdrawal from Southeast Asia and for the University to make a stand. Later that day, Acting President Stoltz and President-elect Donald F. Hornig issued statements (see Pages 7-8) deploring the Cambodian decision but again advocating the need for the University to remain neutral while permitting all within it to follow their own consciences.

The strike had also reached one of its three most critical points on May 5, for the faculty was to meet in a regularly scheduled session. Because approximately 280 of the 500 faculty members with voting privileges showed up for the session, the meeting was moved to Sayles Hall with a delegation of students attending and the deliberations broadcast to the Green, where several thousand students listened to the debate.

The faculty dispensed with its other business and immediately considered the strike and its position on the war. In its first order of business, it approved by an overwhelming vote a resolution presented by Physics Professor Robert Lanou, Jr. The resolution sent to the Rhode Island congressional delegation and to President Nixon read:

"We, the Faculty of Brown, mindful of our responsibility for the education of young people, feel compelled by this responsibility to protest in a most solemn way against the recent series of tragic events which now threaten our ability to carry out our duties, indeed, which threaten even our keenly held national values of freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, and the right to democratic representation. We implore you to use the power and prestige of your respective offices to bring an immediate end to the war in Southeast Asia and to take all steps necessary to end the intolerable escalation of violence by undisciplined units of the police and National Guard, and the erosion of our Bill of Rights resulting from the condoning of these uncivil acts."

Associate Professor of French Edward J. Ahearn introduced a motion, later passed by a vote of 217 to 49, to suspend University functions for the duration of the semester and make optional for all students the decision to participate or not participate in academic functions, exercises and assignments. The motion provided for discussions to be held on the war, its effects on the University, and the relationship of educational institutions to the government. Prof. Ahearn's motion also provided for an assurance of "fair treatment of all students in this period," and turned over to the Faculty Policy Group the responsibility for details to implement the decision in terms of grading and other academic business.

Assistant Professor of Economics John P. Brown also offered a motion, later approved, asking that the faculty of Brown join with other Rhode Island faculties to discuss the crisis and methods of restoring peace. The Corporation, Administration, and student body were asked to send a delegation to Washington to meet with Congressional leaders in support of withdrawal from Southeast Asia, and Gov. Frank Licht '38 was urged to reconvene the state legislature to make the state's position clear in the impending constitutional crisis. Prof Brown's motion also asked that Commencement be reorganized so that all within the University community could use the time to discuss the crisis in the nation.

On Wednesday, May 6, a mass protest meeting was held at the Federal Building, and another would attract a crowd of perhaps 10,000 at the State Capitol on May 8. But by then many already had begun to express dissatisfaction with the same anti-war rhetoric that had been voiced in October and November. By this time, students, faculty, and others, including employees, had begun to organize teach-ins, workshops, the first phases of a mass leafletting campaign at industrial plants and other locations, a state-wide canvass enabling students to discuss the war with Rhode Island citizens, a telephone campaign urging residents to contact their legislators, and the establishment of a speaker's bureau with students and faculty contacting churches, business and industrial organizations.

By Thursday, 65 Brown students ended a 72-hour fast, four mimeograph machines were running at full capacity, and contributions—mostly from students who rejected a number of University services and gave the money to the strike—reached $7,000. It was also on May 7 that the third critical stage of the strike was reached in a mass meeting attended by about 2,500 in Meehan. There, the strike demands were escalated to a platform that called for immediate withdrawal from Southeast Asia, established sanctuaries to protect Vietnamese after the withdrawal is effected, and war reparations to assist in the recovery of Vietnam. The platform established a second point: an end to all political and racial oppression in the United States.

Though the new demands had opposition from a number of segments within the University that felt that the single issue of the war was a unifying factor, the new platform was approved with little opposition. The additional plank of "ending oppression" brought support from the black community, and Brown's Afro-American Society later the next week reflected on that fact with a highly qualified statement of approval, but one that alluded to white concern over the death of the four Kent State students while showing little sensitivity to specific oppression of black people.

The new platform supported by the mass meeting no longer included the demand that the University take a stand; however that point was picked up by a group known as the New University Conference, a coalition of activists who have maintained that Brown's "complicity" is evidenced by government-supported research, its investment portfolio, and military and industrial recruiting on the campus. Regardless of the stand of the NUC, strike leaders have repeatedly stated that their aims are restricted to the two main points of immediate withdrawal and an end to racial and political oppression.

On Saturday, May 9, a committee of 30 students, faculty and employees representing many shades of the strike movement met with members of the Advisory and Executive Committee of the Brown Corporation in a two-hour session that was broadcast to the Green. The meeting gave virtually all of the divergent groups within the strike organization a chance to present their views. The A & E members listened patiently to what most of them later agreed was a tempered, well-organized presentation. Various A & E members spoke to the group, some expressing their displeasure with the war but most of them steadfastly maintaining the need for the University, as an institution, and themselves, as Corporation members but not as individuals, to remain neutral.

At a special meeting of the faculty on May 11, the only significant action taken was the creation of an ad hoc committee to investigate externally-funded research on the Brown campus, with special emphasis on federal sources. At this writing, the matter of "war-related research"—not specifically mentioned in the motion to create the committee—is not believed to be a vital issue if only because it is generally agreed among many observers here that the University is not involved in this kind of research.

As the strike entered its second week, it became increasingly clear that the dictionary definition of the word "strike" was becoming less and less an appropriate term to describe what was happening at Brown. If there was a work stoppage in terms of academic affairs, there were hundreds of examples of students and faculty engaging in what many of them described as "educational experiences that could not be obtained in a classroom situation." And there was considerable disagreement about how much actual academic work was being done if only because of the time of year in which the strike was called. Classes for the second semester had all but ended anyway. The University had entered the reading period before examinations, and the actual amount of academic work being done could not be determined until after a tally was made as to how many students had exercised their option not to take a final examination.

One student, heavily engaged in the strike movement, said it would be dishonest to imply that much academic work was taking place. Science instructors said they were doing business as usual, although class attendance was down. A graduate student was certain that all of his friends were busy cleaning up their academic affairs. A sophomore was busily engaged in strike work when he got a letter from a European university where he hopes to spend his junior year. The foreign university said it would have to see his second semester grades before it decided to admit him in the fall. The sophomore went back to his academic work.

The library staffs claimed book circulation and the use of libraries was down and so was their ability to operate because of a shortage of student help. Another student said he felt the strike was "flagging" and that many were returning to academic work. "Or else," he added, "the strike is becoming institutionalized and more people are at work in the Rhode Island community and aren't as visible." Also, it was true that some students were simply going home—though not as many as expected. Some went home to work against the war in their home community, others just went home.

If, as someone has said, anecdotal research is the bane of clear thinking, then it is probably fair to generalize that except for the leaders heavily engaged in the strike movement, large numbers of students were doing some academic work and spending the rest of their time working in anti-war activities of their own choosing. The option provided them by the faculty decision enabled them to do precisely that.

Athletes also had to face decisions on whether to do business as usual. There was much soul-searching within this special group as there was in the student body as a whole. There were some who remained completely devoted to the game and a few were opposed to playing in contests at all. The bulk of the athletes seemed to be in sympathy with the strike, found their own way to express dissent, but did compete in the remaining athletic contests.

All of Brown's athletic teams finished their schedules and almost all team members did, indeed, find some way to protest, usually through the wearing of strike symbols on their uniforms. In the championship game at Cornell, the lacrosse team wore black armbands. Brown crews wore shirts in the Eastern sprints with the symbol of a clenched fist emblazoned in red. They interpreted this, they said, to be a peace symbol.

Only one contest was interrupted. Some 200 protesters, reportedly led by a former athlete, ended the Brown-Connecticut baseball game. The game was forfeited, but Connecticut refused to accept it. A member of the strike steering committee later said his group would apologize for the act. "This is not the sense of what has happened at Brown and we intend to apologize."

By the end of the week of May 11, it remained unclear in which direction the strike was headed. Many were aware that it could run out of steam unless efforts were

made to maintain enthusiasm on the part of workers for whom leafletting and canvassing could become routine. There seemed little doubt that Brown seniors would concentrate efforts at Commencement in making known their feelings on the war. But students and faculty seemed more interested in reorganizing part of the format of Commencement to enable them to talk with alumni than in dismantling the traditional structure of the event.

The sense of how some students felt about the events of early May was perhaps best expressed by Jeffrey Stout, a religious studies major who was chairman of the steering committee at the outset of the strike. Said he, at an alumni seminar to explain the strike:

"The strike is dedicated to communicating what is on everyone's mind. There has been excellent discourse between faculty. Corporation members, people in the community, and students of every point of view. Something beautiful has happened because people are now getting down to what has been bugging them for a long time. We have favored methods which persuade, not coerce; which discuss and not pressure. Everyone knows that, and that is exactly what has been happening here."

'Do not sacrifice Brown to the growing determination to change America's foreign policy'

by Merton P. Stoltz

(Repeatedly since the strike began, various groups within the University community have asked that Brown, as an institution, endorse the two basic demands of the strike. Acting President Merton P. Stoltz said the first days of the strike would be critical to Brown and added the following statement.)

President Nixon's decision to invade Cambodia and to resume the bombing of North Vietnam has alienated millions of young Americans. In their rage and feelings of helplessness many of these young men and women have already lashed out at what they consider national insanity. Many campuses have erupted in violence.

I share—as most Americans must—the students' sense of despair, anger, and frustration over the escalation of the war in Southeast Asia. It is impossible for me to imagine any foreign policy gains that could possibly compensate for the deep, perhaps irreparable, divisions that the President's war policy has caused in the society. There are strong indications that the republic is moving toward a constitutional crisis, with all of the grave implications that such a crisis portends. We are not simply talking about foreign policy or domestic politics. We are considering the soul and the survival of this republic.

The majority of students and faculty of Brown, like students and faculty throughout the nation, have been earnestly seeking ways to register their protest and influence their government. They have voted to participate in a national strike and in so doing to formulate their feelings and plans and to dramatize them.

In mass meetings of students and faculty [on May 5], the majority of the campus community voted for the immediate withdrawal of the United States from Southeast Asia. This is what they are saying to their fellow citizens. They are prepared to work in rational and effective ways to convince all Americans to join them.

As acting president of Brown I have no responsibility more important than preserving on this campus the freedom for any person or group to dissent without fear of repression, to express any point of view, and personally subscribe to any political philosophy. The University must assure a forum where all ideas can be accommodated, no matter how critical of society or government. It must remain an independent institution where individuals are free to question, criticize, and analyze the affairs of men and societies. This is the unique mission of the university and one of its most important contributions to society at large.

Now, more than at any time in recent years, there is an urgent need for wisdom to match our passion, for effective action to match our rhetoric, for a sense of unity to bind us. The decisions made and the actions taken will have important consequences for the nation as a whole and for the universities themselves.

As the acting president of this University, I am compelled to implore [those within the University community] not to sacrifice Brown to the growing determination to change America's foreign policy. The University can and should be used as a forum where the forces for change and reform can be heard. But it is too fragile an institution to be used as a battering ram to force changes in society. There are those who would like nothing better than to see us divert attention from the real problem in a futile and destructive quarrel about the role of the university.

I understand why many individuals feel that it is imperative for Brown to stand up and be counted in a situation which has such grave implications for the world and our nation. As members of this University, they want it to reflect the moral indignation they feel so deeply, and they want it placed on the side which they support.

It is very difficult to convince those who feel strongly about this of the dangers inherent in such action. I have expressed again and again my absolute conviction that a university must not take stands on contemporary political issues, however grave, except where its own freedom and integrity are directly threatened. Many refer to this "neutrality," a term used with scorn to describe a philosophy which many find unconscionable in a time when world security is threatened and our society is being torn apart.

There have been countless crises in the years past, innumerable threats to world peace and society. There will be many, many more. For centuries the university as an institution has been under enormous pressure to adopt the cause or the philosophy of one group or another. The pressures continue now and will continue in the future.

At the heart of the issue, then, is the very survival of the free university. How can a university take a corporate stand on anything but its own freedom and functions without denying the dissenting voices of some of its members? What institution will accommodate all ideas, no matter how critical of society, if the university becomes the sponsor of any one idea or course of action?

The essence of the university is its absolute commitment to provide on the campus a free forum for all. There is nothing in our United States Constitution which guarantees this freedom to universities and their faculty and students. It flows from a tradition which has been continuously assaulted and continuously defended over the years. It is precisely because this principle has been defended and preserved that we on this campus are free to dissent from the war and to make demands upon this University.

If those who press for an end to this principle were to be successful—regardless of how humanitarian their motives may be—they must recognize that the rights and

freedoms of future generations of students and faculty to think and say what they believe would be lost. Once the university deliberately commits itself to a political cause where its own freedom and function are not directly threatened, it will lose its right to claim objectivity and impartiality.

And it is on the basis of this claim, on the ground that at least one institution in a society must be free to question, criticize, and dispassionately analyze the affairs of men, that society has granted this unique academic freedom to universities. If universities become political agencies, they will be forced to accept the consequences. The people will no longer be able to trust the university's unique claim to total exemption from repression as the impartial home of diverse and even subversive ideas and opinions.

Those who sincerely urge the University to take a public stand against the war in Southeast Asia point out that the American university has not always maintained its objectivity, that its actions in the past have sometimes placed it in the service of the "establishment" or the status quo. That criticism is unfortunately true. There have been times when universities allowed themselves to be used in support of widely accepted national goals without even recognizing the degree to which their integrity was being compromised. But surely the failure to live up to principle in all respects is no justification for deliberately violating that principle now or in the future.

Devotion to academic freedom does not imply consent by silence. On the contrary, the University can, should, and must be used as a forum where the advocates of change and reform can speak out. That forum is protected by refusal to speak ex cathedra. It is endangered by pretending to speak on behalf of all. How can "the university" even do that?

I know there are profound issues which plague us as a people. I know that as a civilization we are being forced to deal more and more in terms of absolutes. But I also know that much of mankind's hope resides in the university—in its ability to seek and discover answers, its success in humanizing and enlightening the young, and in its determination to remain free and independent of all forces that would bend it to partisan ends.

At the moment, at least, we are fortunate, for only the members of the University can succeed in turning it into a political agency. If they succeed, they will be doing a tragic disservice to themselves, to their children, to the University, and to the very freedom they profess to cherish.

'Thoughtful, idealistic and frustrated. Certainly they are not bums’

(Donald F. Hornig, president-elect of Brown, sent the following wire to President Nixon following the Cambodian decision and the death of the four students at Kent State.)

As a concerned citizen who will soon take office as president of Brown University, I feel compelled to make my views known.

The last few days have seen a series of tragic events which have dismayed not only students but a large number of thoughtful people of all ages. A war from which we thought we were withdrawing has been abruptly escalated and broadened. The American people are deeply divided by actions which seem immoral to many of us.

Protesting students have been killed by troops ostensibly mobilized to prevent violence.

It should be clear to everyone that the students who protest are not just a radical fringe. Most of them are thoughtful, idealistic young people who are revolted by events and frustrated by the refusal of their government to consider their views. Certainly they are not bums.

If I were presently in charge of Brown I would do my best to keep the University open to those who want to study and complete their courses this spring. Certainly I would not condone violence or illegal acts. But my heart would be with those who see a duty to explain to their parents, their friends, and their communities the reasons

for their deeply-held convictions. I would personally support our efforts to arouse the Congress and the people to the dangers which confront our beloved country.

The universities of this country are a precious asset. One of the tragedies is that the actions of our government are playing into the hands of those who would destroy them.

I appeal to you, Mr. President, to reverse the course of action you have taken in Cambodia and North Vietnam and to continue immediately the disengagement of our troops in South Vietnam. I urge you also to listen seriously to what our young people have to say.