Is Careerism Ruining College?

The race to position yourself in a tight job market now takes over every college summer vacation, and even high school seniors ask professors how they can get a leg up. As college costs rise, how much should Gen Z students be emphasizing career prep? And what might be lost?

Nyria Delph ’28 was the muckraking editor-in-chief of her high school newspaper at Overland High School in Aurora, Colorado, so her Spanish teacher was a little surprised when Delph asked for a letter of recommendation for Brown around her plans to be a pre-med student. “You’d be a great doctor,” she recalls the teacher saying, “but I see you more as a reporter.”

But Delph, part of the first generation in her family to attend college, wanted to keep pushing on both fronts. Before senior year of high school, she’d done the summer journalism program at Princeton and immediately joined the Brown Daily Herald when she arrived on College Hill last September, even as she also joined the Black Pre-Med Society, volunteered at a Rhode Island health program, and attended a medical conference on suturing.

“I wrote in my application [to Brown], the Open Curriculum gives me the opportunity to be a risk taker,” Delph says, and so far she’s living up to that. But she admits that some of her friends on campus who share her med-school ambitions don’t understand why she toils for the newspaper or her idea that she might take a gap year after Brown. Some, she says, began pushing for the right internships or other resume boosters not long after freshman orientation, including one who was cold-calling her new professors for recommendations. She laughs as she recalls telling them, “Guys, we don’t know anything yet.”

Delph’s tightrope act of pushing forward with her career goal in medicine yet also making the most of Brown’s opportunities to chase scoops in daily journalism, along with taking classes in the humanities, epitomizes a nationwide debate that is increasingly defining college life for undergraduates at the midpoint of the 2020s.

The fundamental questions: Have the scales of academia—weighed down by soaring tuition and the expensive real world that awaits Gen Z college grads—tipped too far toward pre-professionalism, a term for careerism on steroids? And are students too focused on getting into the right campus clubs and nabbing the perfect internships to reap the

advantages of a diverse, liberal-arts education?

For Sangeeta Bhatia ’90, liberal arts and high-level career success are not contradictory concepts—they’re directly related. While Bhatia says her parents told her she could choose from three careers, doctor, engineer, or entrepreneur (she became all three, with a PhD to boot), she feels her coursework in humanities was key to her ultimate success as a biomedical entrepreneur. Bhatia runs her own cancer nanotechnology lab at MIT and has launched eight biotech companies. In 2014 she won the Lemelson-MIT prize, known as “the Oscar for inventors.” She says her time on College Hill helped convince her that science cannot advance without an appreciation for art and the humanities.

“I describe the process of invention as a bit like writing a song,” Bhatia says. “You start in one direction and make it up as you go. You form collabs with others. You riff. Creating something out of nothing and imagining the future requires inspiration—and to be inspired, students need to be exposed to as much outside of their field as in it.”

Yet Bhatia’s belief that liberal-arts exposure was essential to her success as an innovator and earner isn’t reflected in the paths many Gen-Z undergrads are taking. The popularity of career-path majors such as business or computer science has skyrocketed as enrollment in subjects such as sociology or English literature has plunged to

record-low levels. A trend toward layoffs or department closures on some campuses, even as some small liberal-arts schools are shuttered entirely, provoked a story that exploded last September. That’s when a 2023 University of Pennsylvania grad and law student, Isabella Glassman, published her widely read and provocative New York Times op-ed: “Careerism Is Ruining College.”

“I’d wake up at 3:30 a.m. from the recurring nightmare that I didn’t land an internship my junior year summer,” Glassman wrote. “I heard people, maybe friends, endlessly discussing the ‘only way’ to be successful. I consoled a sobbing roommate after she failed to land the job her parents expected her to get.” The Penn alumna’s article chronicled the surge of students (herself included) studying microeconomics, vying for elite summer internships on Wall Street or Silicon Valley or Capitol Hill, or getting crushed by rejection from elite societies like Yale’s investing club. And it launched a national conversation about pre-professionalism and a potential link to rising rates of depression among college students, even—or especially—on elite campuses.

Not a new debate

One could argue that this debate has been taking place since Italy’s University of Bologna handed out the first degree in the early 1000s. The question that’s always lurked underneath: What is college really for? Should higher education focus on narrow career skills—from building ancient stone bridges to today’s coding for artificial intelligence—or a well-rounded liberal curriculum that hones critical thinking skills and a love for the arts? In recent years, the popular, idealistic stance has been to herald the higher purpose of the university as a molder of tomorrow’s great thinkers and citizens, even as rising financial ambition fuels applications for Goldman Sachs internships and lengthy LinkedIn profiles at age 18.

In his 2005 commencement address at Stanford University, the late Apple cofounder Steve Jobs told the story of how he indulged his love for the art of calligraphy in his coursework and during his free time as an undergraduate at Reed College, without any sense there’d be a connection to his bigger career ambitions in tech.

“I learned about serif and sans serif typefaces, about varying the amount of space between different letter combinations, about what makes great typography great. It was beautiful, historical, artistically subtle in a way that science can’t capture, and I found it fascinating,” he said. “None of this had even a hope of any practical application in my life. But 10 years later, when we were designing the first Macintosh computer, it all came back to me. And we designed it all into the Mac.”

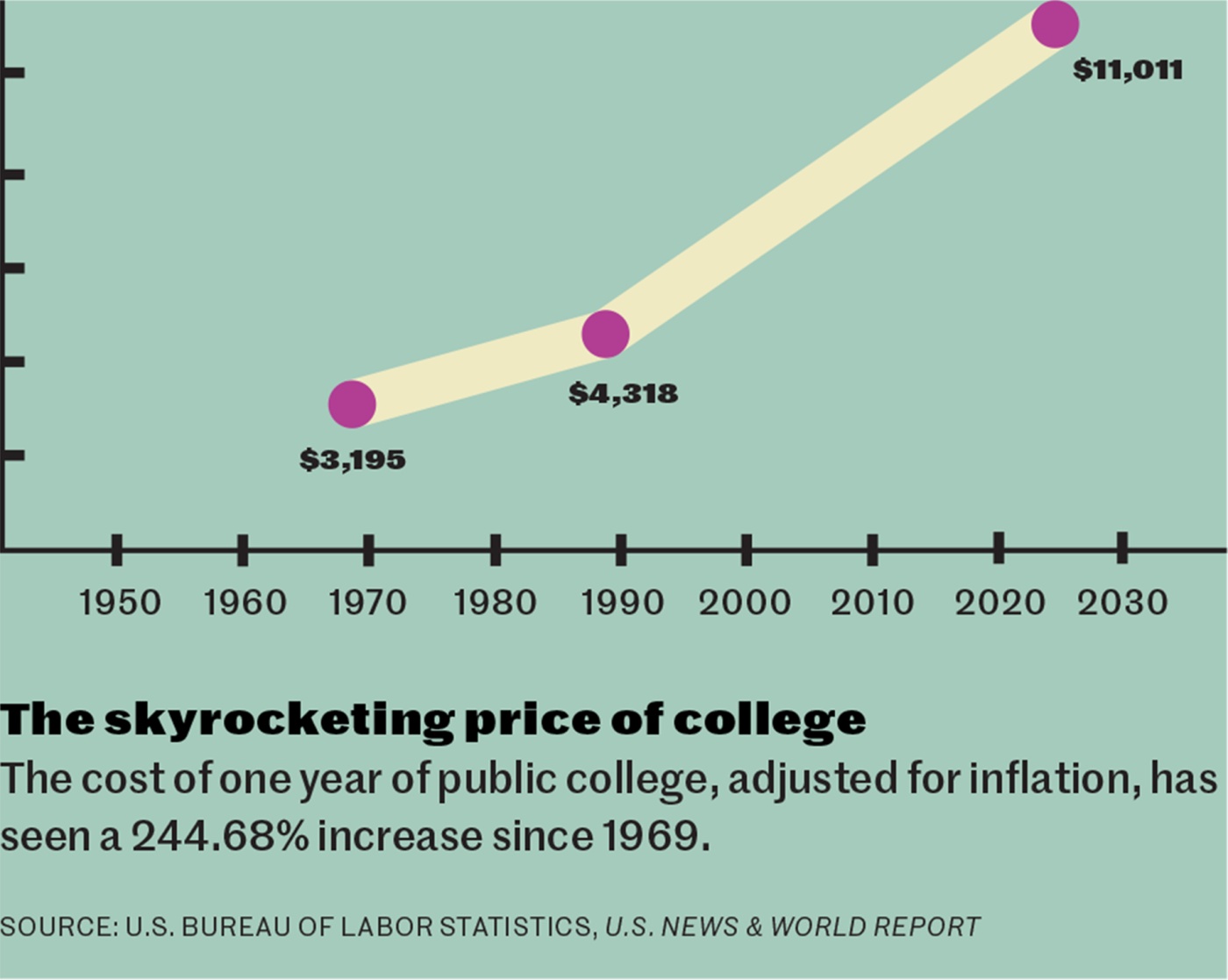

Yet even as graduates at Silicon Valley’s flagship university were applauding Jobs’s lofty message, societal trends were undercutting it. A tougher job market, the ever-rising costs of large cities where the best opportunities were centered, and the exorbitant hikes in tuition convinced many young people that a four-year-long laser focus on the most lucrative career is what’s required in modern America.

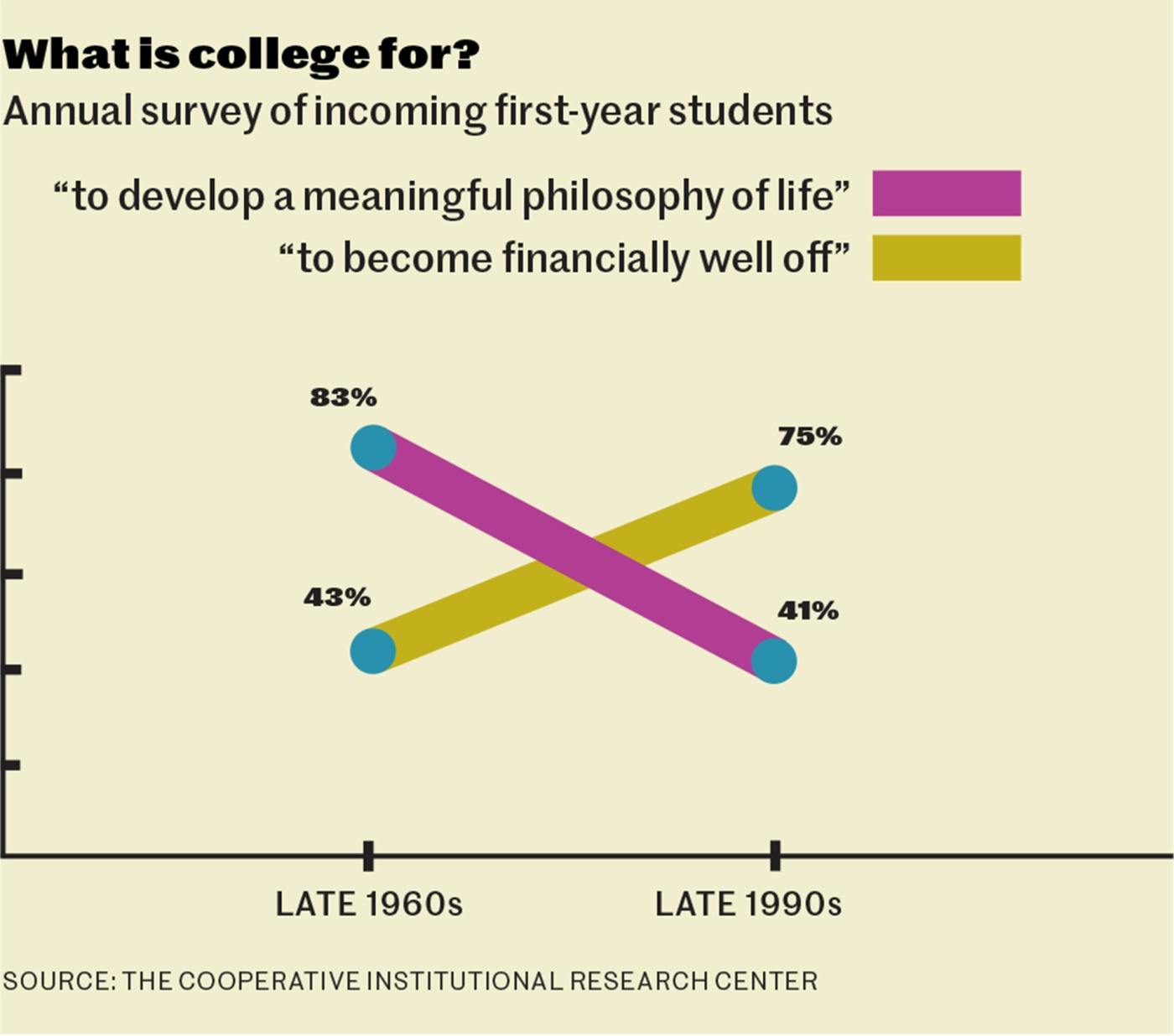

Consider this: For decades, researchers at UCLA conducted a nationwide survey of incoming college freshmen to gauge their attitudes. In 1969, after two decades of prosperity in which tuition at thriving public universities was low, or even nonexistent, a whopping 83 percent of first-year students told the survey that a chief purpose of college is “to develop a meaningful philosophy of life.” But that number had already fallen to just 41 percent by the Wall Street–crazed mid-1980s. Over the same period, first-year students who said they were at college to become “financially well-off” soared from 43 percent to 75 percent.

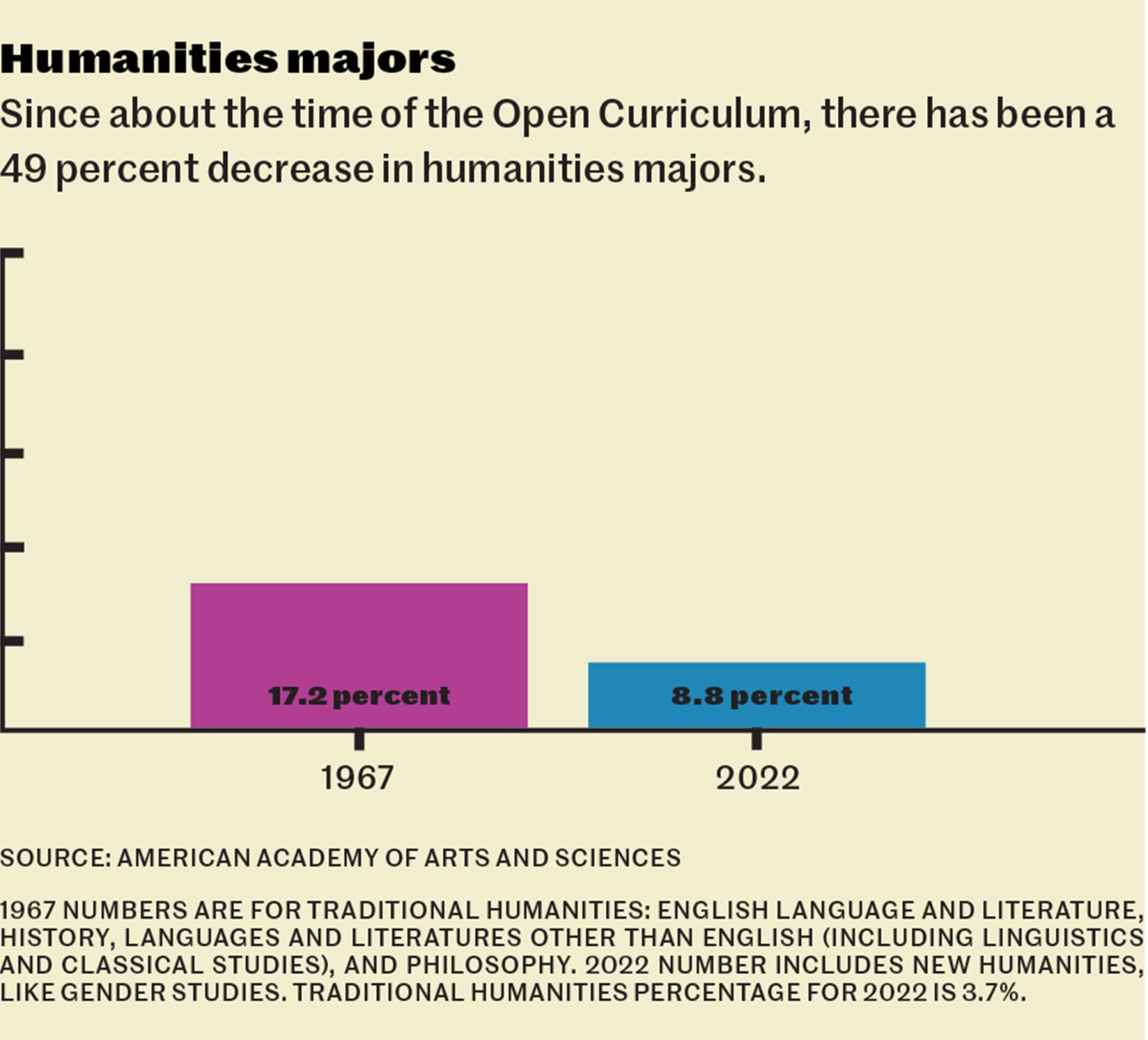

These trends have only accelerated in the 21st century. In 2022, the humanities accounted for just 8.8 percent of all bachelor’s degrees, down from 15 percent in 2005, the year of Jobs’s stirring commencement speech, while schools such as Marymount University and St. John’s University have cut liberal-arts majors and minors. But even those stark statistics don’t fully capture today’s angst for many students as a competitive infrastructure of increasingly selective clubs, internships, and other extracurricular programs makes the career pipeline a lurking, everyday presence in the modern college experience.

Jocelyn Frelier, the associate director of the Brown in Washington program, who works closely every semester with a dozen or so Brown undergraduates working for credits on Capitol Hill or elsewhere in the vast bazaar of Beltway politics, says a couple of years ago she was “amazed” to get summer emails from just-accepted applicants asking what they should be doing “now” to later nab a top D.C. internship. “They had been at Brown for five minutes and they were already thinking about internships,” she recalls. She drafted a universal response to “get settled and call me in a year.”

Frelier, who wrote an op-ed for Inside Higher Ed in response to Glassman’s explosive essay in which she urged college administrators to do more to tamp down careerist anxiety, worries that today’s students have been raised to be judged largely by their accomplishments, compounded by the financial demands of an unequal U.S. society. “I think students feel pressured to chart a course and stay on it and never look back,” she says, even as she notes one of the actual successes for a program like Brown in Washington is when students discover that maybe politics, or a specific type of job in Congress, actually isn’t for them after all.

Indeed, even while Frelier and other Brown administrators amp up career-focused offerings such as internship, they stress the so-called “soft skills” that Brown students develop as they move toward adulthood. Frelier says another recent victory was working with a student who wanted to use her time in the capital to not just add a political job on her resume but to finally learn how to cook in an off-campus apartment. “I like to diversify the idea of what achievement can look like—like the idea that you made a veggie lasagna from scratch,” she says.

“In the ’20s and ’30s, you went to school because you’re a guy, you’re white, and it’s where you met and networked with other white guys who could afford it.”

How the Open Curriculum fits in

This debate over pre-professionalism—whether its pursuit has gone too far and what to do about it—is now taking place on campuses across America, but it is taken especially seriously at Brown. The 1960s-born revolution in academic freedom that has evolved into today’s Open Curriculum emphasizes the very values—a broad liberal education that encourages students to experiment in an array of subjects—that seem in direct conflict with extreme careerism.

Brown’s unique history also reveals how the campus tension between the allures of a classical, liberal education and what we now call pre-professionalism has always existed. It might seem ironic today, but the 400-page 1968 report by then-undergraduates Elliot Maxwell ’68 and Ira Magaziner ’69 that led to the Open Curriculum—which ended rigid requirements for courses outside a student’s major, lowered the number of credits for graduation, opened up a pass/fail option, and expanded interdisciplinary seminar-style courses—slammed what it saw back then as “narrow professionalism.”

What was initially called the New Curriculum—at first at odds with Brown’s then-president Ray Heffner, who said “the University is not a participatory democracy,” and which was won only after large student protests—came to define the Ivy League campus in the latter part of the 20th century amid its growing popularity and a new and improved image as a bastion of liberal learning.

And yet almost from the very first semesters of the Open Curriculum, Brown and its leaders were pushed to balance this liberal approach with the growing career pressures of the American economy. In the spring of 1974, with long gas lines and a brutal job market, two undergraduates convinced Professor Barrett Hazeltine to launch the class then known as ENGN 9, which aimed to teach managerial entrepreneurship as a different kind of liberal art. Brown also added its medical school in the 1970s—some objected to medical education as “career prep” at the time—but with an innovative twist that admitted top high school seniors for an eight-year accelerated program meant to encourage them to take more electives as undergrads.

Arnold Weinstein, professor emeritus of comparative literature, arrived at Brown in 1968—just in time to play a key role in the invention of what is now the Open Curriculum, working with the legendary professor George Morgan to meld science, literature, and philosophy in new interdisciplinary programs such as a “Human Studies” major. Weinstein, who taught for 54 years, says that Morgan—who died in 2023 at age 98—taught him that “you can’t truly understand your discipline until you leave it.”

Weinstein has spent his latter years as something of an evangelist for the great books, once lecturing Yale med-school students on “Why Read Kafka?” and writing a 2022 essay in the Brown Daily Herald pleading for more students to study literature. He wrote that “important books shine a unique beam on human behavior, thought, and feeling. Reading these books adds something unique not only to our database but to our actual identity. For we’re never through discovering who we are.”

Yet Weinstein’s battle is an uphill climb. While his life in academia has overlapped with steep declines in once-popular majors like philosophy and sociology (which were 4 percent of all bachelor degrees in 1972 but barely 1 percent today), there has been a corresponding rise in campus groups closely tied to career preparation, especially in the most lucrative fields such as finance or entrepreneurship.

Exploring vs. Networking

At Brown, the 2000s heralded the arrival of pre-professional clubs that now include Brown Consulting Club, Brown Finance Club, and Brown Investment Group, as well as affinity groups for Black or Latino students preparing for careers in business or medicine. “We try to help guide people in education and mentorship,” explains Thomas Yun ’26, the operations manager of the Brown Investment Group, who is studying applied math and economics and is leaning toward a career in finance after also weighing military service.

The group’s efforts include a competition—sponsored by James Kovacs ’11 and James Hollier ’18, founders of the New York–based investment manager Silver Beech—that aims to expose students to finance outside the classroom. The students pick a publicly traded company and make a pitch, and the four finalists have the opportunity to present before accomplished alumni. “It gives them a relationship they can build upon and some exposure in the real world,” Kovacs says.

Emily Hipchen, director of the nonfiction writing program at Brown, noted there’s a back-to-the-future element in this push for networking, reminiscent of the old-boy connections that characterized higher education prior to 1944’s enactment of the G.I. Bill that triggered a more egalitarian era on campus. “In the ’20s and ’30s, you went to school because you’re a guy, you’re white, and it’s where you met and networked with other white guys who could afford it,” she says. “It supported the kinds of friendships that gave you access to power and money. It didn’t matter if you had a job because you weren’t looking for skills, you were looking for buddies.”

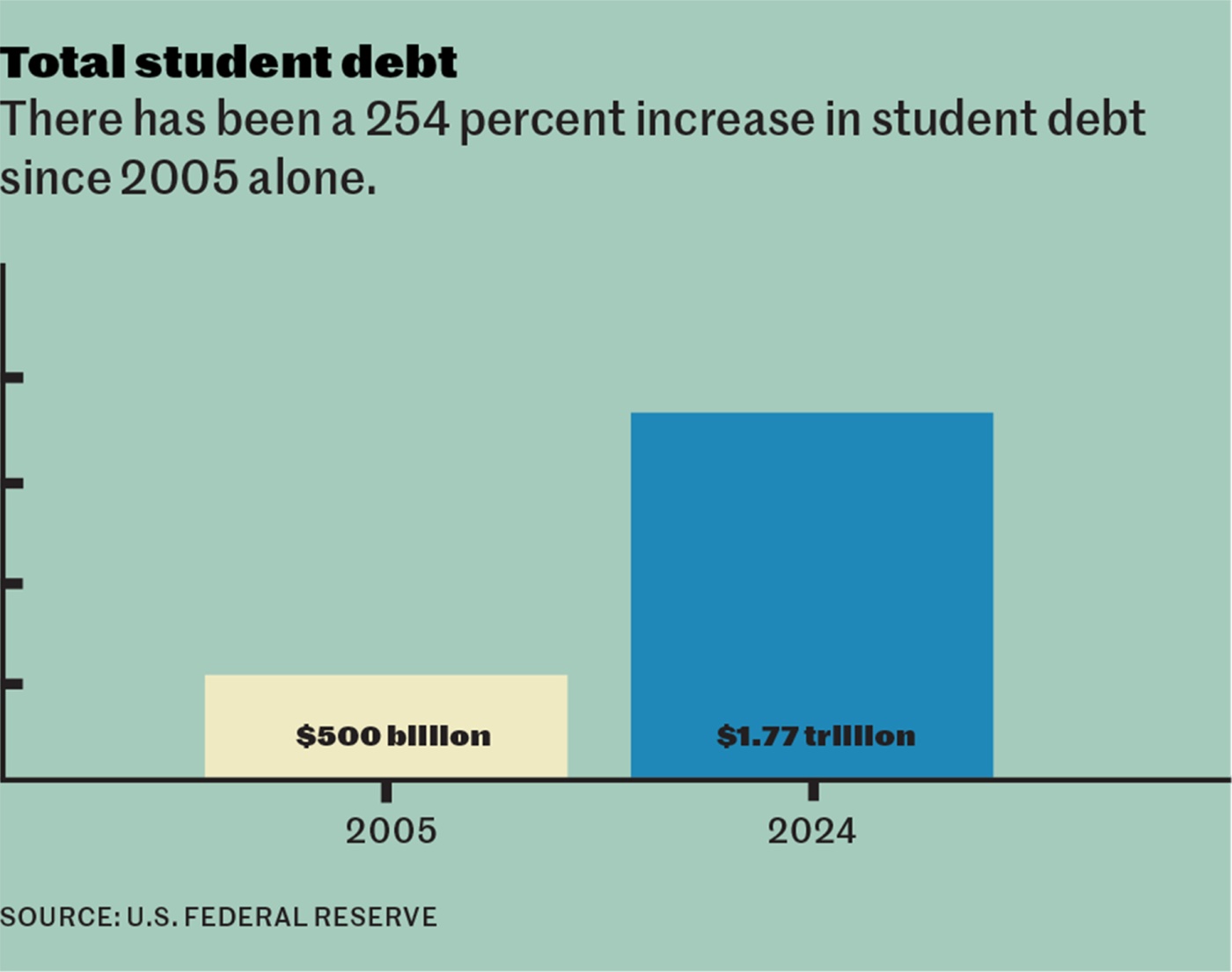

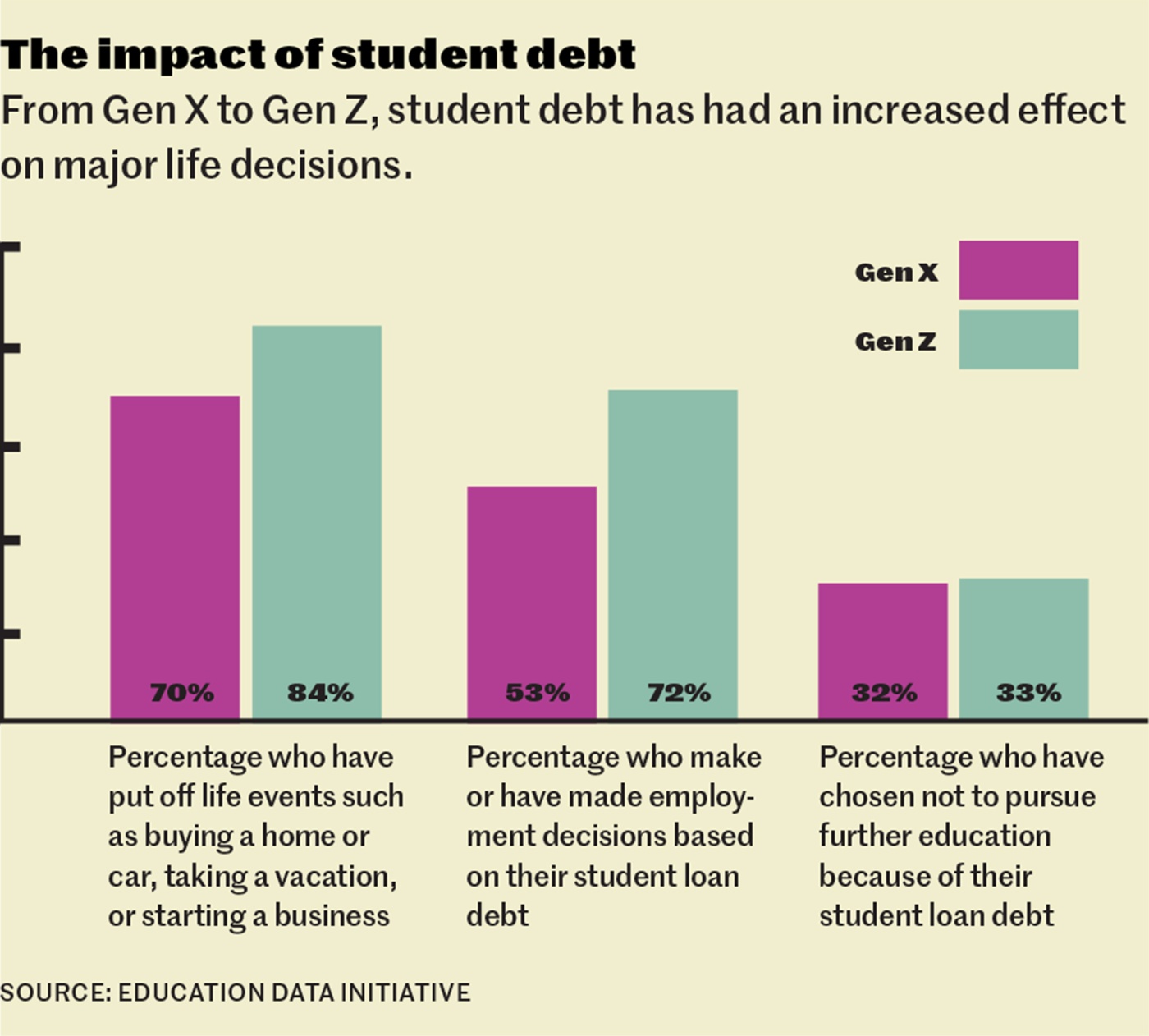

The good news is that today’s pre-professionalism isn’t restricted to a certain class of elite white young men, but the bad news is that it’s driven by a sense of economic urgency attached to making the right connections and boosting one’s profile on LinkedIn, the career-oriented platform where today 20 percent of the users are aged 18-24. Nationally, student debt has soared from about $500 billion in 2005, the year that Jobs spoke at Stanford, to a whopping $1.77 trillion in 2024, according to the U.S. Federal Reserve.

Students weighed down by these loans also know the best jobs for repaying them tend to concentrate in expensive places like Silicon Valley, New York, or Washington, with astronomical housing costs. The burdens come down hardest on middle-class kids, especially Black and brown students, who might be from the first generation in their family to attend a university and who thus want to make the most of their opportunity.

“The days of being a lifeguard at your local beach…those are gone,” says Brad Gibbs ’93, ’18 MAT, a senior lecturer in the economics department who teaches classes in corporate finance and financial institutions. “That just doesn’t happen anymore.” Instead, Gibbs says he sifts through emails from students asking him about working on summer research projects, even if he wonders how much the inquiries are geared toward resume building as opposed to a genuine passion for economics. The former English major at Brown, who headed investment banking for Morgan Stanley in South Africa before returning to academia, says one problem is that many top Wall Street firms start recruiting student talent when they are just sophomores. “You can’t decide your senior year that, ‘Oh, now I want to go do this,’ because you’re too late,” Gibbs says. “They’ve already hired from their junior summer analysts who they selected in sophomore spring.”

In her New York Times essay, the recent Penn grad Glassman discusses the dark underbelly of this competitive environment, arguing that there’s likely a link between pre-professional pressures and a doubling from 2010 to 2020 in the number of young adults aged 18 to 25 reporting a major depressive episode, as well as a study in which two-thirds of college students said they’d felt “overwhelming anxiety” in the last year.

At Brown, many new students who picked Providence over other elite college destinations say the promise of academic exploration embedded in the Open Curriculum is what drew them up College Hill, yet they felt the cross-currents of pre-professionalism almost immediately. “As soon as I set foot at Brown, I was blasted with all these clubs” as well as with information about corporate internships, recalls Hans Xu ’26, who is studying a combination of applied math, economics, and international affairs and recently interned with the U.S. Trade Representative through the Brown in Washington program. “It was like, you need to check a box and jump through these hoops.”

Today, students who arrive in Providence with a pure and focused love for the arts or humanities or the social sciences understand they are bucking the headwinds of careerism. Brown senior Giuseppe Canta ’25, an Italian native raised in Naples and the United Arab Emirates, crossed the Atlantic because the Open Curriculum offers such a stark contrast to the academic rigidity he saw on European campuses. He has stuck with the subject he arrived most passionate about, philosophy, while adding a second major in comparative literature. He hopes to stay at Brown for his philosophy master’s degree and, down the road, navigate the tight job market of academia. “I’m very grateful that my parents support me,” Canta says, “because it’s not the thing that’s the easiest to make a living off, but they’ve always prioritized my happiness.”

Writing program director Hipchen argues that the secret power of a college degree isn’t the sum of its Wall Street internships but its gift of “a hothouse space” of interesting ideas and people. “It’s the personal richness that you find in the intersections of the classes you take, the late night conversations you have with people about things that may never show up again after you leave college,” she says. “I am entirely not who I was when I went to college, because of college.”

“As soon as I set foot at Brown, I was blasted with all these [pre-professional] clubs. It was like, you need to check a box and jump through these hoops.”

Indeed, the ultimate irony of pre-professionalism in the 2020s is that hiring executives at major corporations increasingly seek graduates with the kinds of critical thinking, communications, or just basic life skills that emerge from a top-flight liberal education rather than narrowly focused knowledge about current computer coding.

“Liberal arts is more relevant now than ever because we don’t know what the jobs of 10, 20, or 30 years from now are going to look like,” Matthew Donato, the career center head, says. “Look at AI and the types of jobs and opportunities that new technology has created. People a decade ago weren’t talking about the types of jobs that exist in AI now. I believe the skills that students learn through a broad liberal arts education are critical to being flexible, to being adaptable, and to preparing students to navigate their future careers.”

“I teach environmental science and quite honestly, fifteen years ago, the number one question was ‘What the heck do I do with this degree? It might as well be poetry,’” says Dawn King, Brown’s deputy dean of the college for curriculum and a senior lecturer in environment and society. “I had a student who double-concentrated in economics and environmental studies. When she got a really competitive job at Fidelity in New York, she said, ‘Do you want to know why I got this job? Because I was competing against all econ majors. I was the only one who also had an environmental science degree.’ That’s what made the difference.”

Will Bunch ’81 is national opinion columnist for the Philadelphia Inquirer and author of several books including 2023’s After the Ivory Tower Falls. His family once owned a small business college. Additional reporting by Lorraine Ali.