Science Fair Dropout

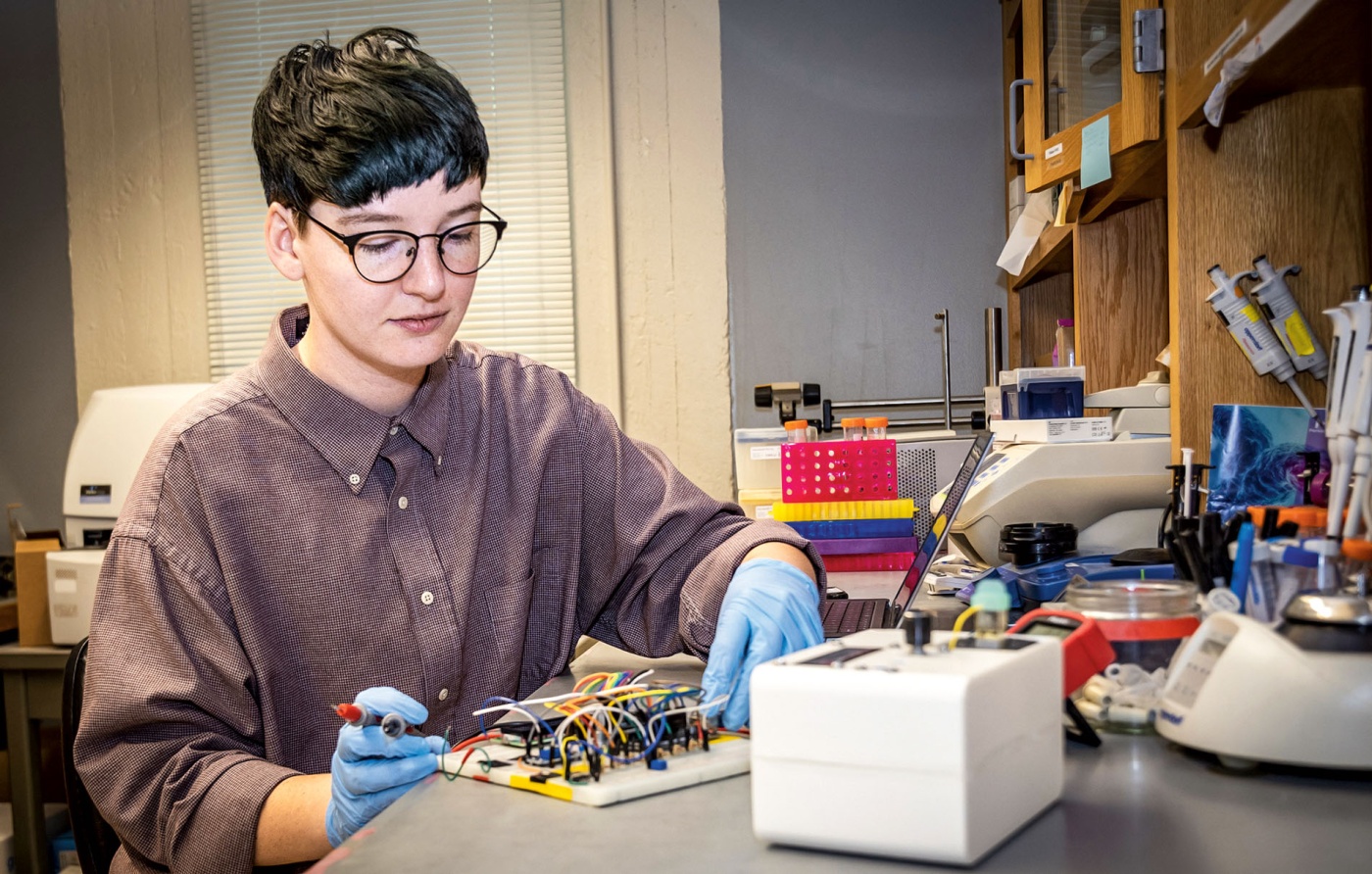

Bioengineer Cel Welch creates devices that streamline cancer detection.

For a New Jersey science fair, Cel Welch ’22 ScM, ’24 PhD—then age 12—designed a pair of dirt-resistant socks to keep the family dog from tracking mud into the house. The judges deemed the submission “not science” and booted them from the competition. Undeterred, Welch spent the next 14 years designing ever-more-complex experimental devices. In 2023, they were named to Forbes’s 30 Under 30 list in science—their research wasn’t just “scientific,” it was some of the most groundbreaking innovation that the field of medical technology had recently seen.

Welch’s interest in science was always more practical than theoretical. As an undergrad at

McGill, Welch would query their biology professors about the devices they used. “I would go up after class and say, can you tell me how this works, and they’d be like, we don’t make the machines, we don’t know,” Welch remembers. “I said, I want to be the person who makes the machines.”

Welch’s desire to design machines led them to Brown to pursue a doctorate in bioengineering. By the time they completed their PhD, they had written 13 papers and filed 5 patents, mostly in the field of cancer detection.

In the lab of their mentor, professor Anubhav Tripathi, Welch created a new method for breaking down tissues using electrical fields. The process is remarkably effective at separating individual cells with minimal damage, so the cells can be used to biopsy cancer at high resolution.

With pathology professor Joyce Ou, Welch devised a method that uses machine learning to automate detection of cancer cells in pap smear slides. “It typically takes two hours for a clinician to do this, so it really cuts down on the labor required,” says Welch. The technique also more accurately detects cervical cancer at a precancerous stage.

Despite their outstanding record as a young scientist, Welch didn’t always feel welcome in the academy because of their identity as a trans person. “People underrepresented in STEM often have to prove themselves several times over to convince others that they are deserving of their seat at the table,” Welch says. “I’ve often had the experience of coming into an environment that is not ready to receive me and meeting with a lot of resistance. There is an aspect of having to prove yourself before people will consider you credible.” While at Brown, Welch advocated for greater acceptance of LGBTQ+ scientists as president of oSTEM@Brown (Out in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) and head of Queer Engineers International.

Welch dedicated what little free time they had during grad school to exploring hobbyist electronics kits. Now, they’re applying what they learned as a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford, working with chemical engineer Zhenan Bao to create flexible electronics that can be implanted into the body. “Traditional electrodes are very rigid,” Welch says, making it difficult to integrate them into tissues. In this case, the more flexible devices will be used to help better map and monitor the heart.

Welch says the “cool dual expertise” in biology and engineering they developed during their PhD enables them to make the machines that could lead to the next big breakthrough in medicine. “These devices are the basis of what a lot of fields are built on,” they say. “If you want to make a big change in medicine, one great way to do that is to redesign or invent a new tool.”