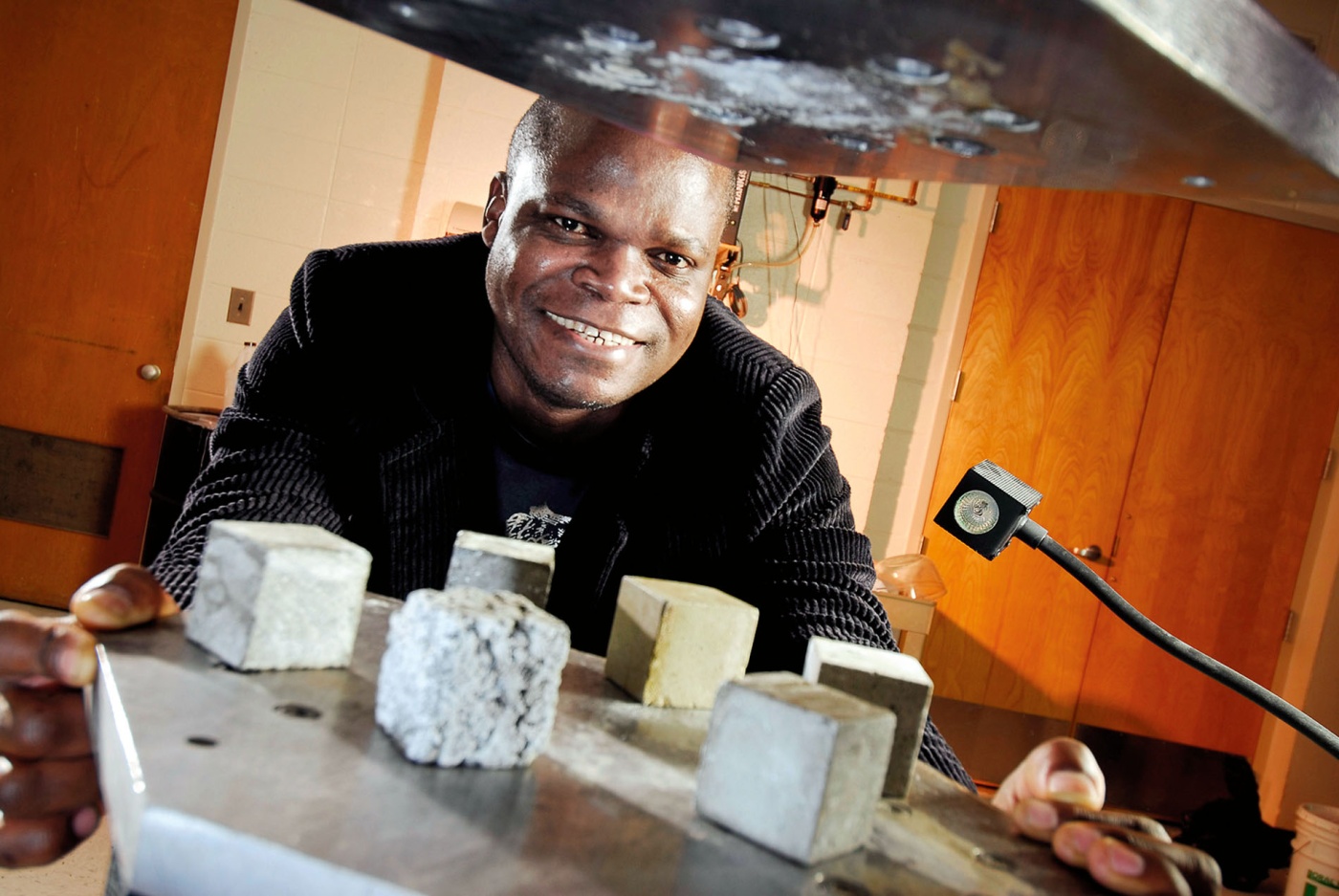

‘What Could Be’

Visionary inventor Mulalo Doyoyo saw potential everywhere—and acted on it.

Mulalo Doyoyo ’95 ScM, ’96 ScM, ’00 PhD, was raised under apartheid in Johannesburg, South Africa, vaulted through advanced degrees in the U.S. into a professorship in engineering, then returned to South Africa to put his knowledge and boundless creativity to work finding practical solutions to everyday problems—solutions that often reused harmful materials and could benefit poverty-stricken communities like the one he came from. A renowned researcher in applied mechanics, ultralight materials, green building, and renewable energy, and also known as the inventor of cementless concrete, he passed away unexpectedly in his hometown March 11 at 53 years old.

As a child, Doyoyo and friends would pass the time firing slingshots at clay pots. Most would disintegrate; his grandmother’s did not. What was her secret? He discovered that she mixed a slimy secretion of riverine frogs into her clay and his fascination with engineering was born.

While attending the University of Venda, he obtained superlative scores on an IQ test by Anglo American and was awarded a scholarship to study mechanical engineering at the University of Cape Town, where he was a student representative of the South African Institute of Aerospace Engineers, a founder of the student aerospace society, and president of the student engineering council. He created Temescial, an organization aimed at exposing underprivileged high schoolers to engineering; it held its first workshop at the University of Venda in 1993. He then traveled to the U.S. and earned two master’s and a doctorate at Brown before being accepted into a postdoctoral research position at MIT to enhance his studies in applied mechanics. He left in 2004 to lecture at the School of Civil and Environmental Engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta, where he created an ultralight systems lab dedicated to experimental research and accidentally invented Cenocell, a cementless concrete. It can be produced without the burning of fossil fuels, reducing the carbon that would otherwise be emitted into the atmosphere in the normal production of cement.

He returned to South Africa in 2011 with the knowledge and skills to help his native country. There he was responsible for many more innovations, including the primer paint Amoriguard, which he discovered when he accidentally kicked over a bucket containing a combination of materials he’d made to solidify coal dust for reuse. As he later told News24.com: “I invented this paint by pure accident when I kicked the bucket.” Now a commercially sold paint produced in a Cape Town factory, Amoriguard has been used in projects across the country. “This material could help develop communities by allowing people living near coal-burning facilities to create a new industry and new jobs,” Doyoyo said in an interview with ReliablePlant. “This could be an engine of development for people who have been struggling. It really is a material with a social conscience.” He later described it as “the future of paints,” adding, “Africa has arrived and it will be nice when an African child walking along the streets of New York is asked what Africa has done, and they can say: ‘Africa has painted the buildings of the world.’”

It wasn’t his only invention with a social conscience. In 2014 he worked on solar-powered toilets that operate as miniature waste-treatment plants. Based on nanofiltration and anaerobic digestion, the tech is now implemented in places where water supply and sanitation are scarce. He also created Ecocast brick-making machines, which save water and energy by using industrial waste products to produce structurally robust bricks. At the time of his passing, he was about to start work on a solar project in a village that would ensure, during load-shedding, that the whole village would have electricity for 12 hours nonstop.

Speaking on behalf of the provincial government during his funeral, Limpopo’s Member of the Executive Council for Health, Dr. Phophi Ramathuba, said: “Professor Doyoyo has not just been an inventor; he has been a visionary who has seen beyond the immediate to the potential of what could be. Through his brilliance and determination, he shattered barriers, turning the challenges of poverty and apartheid into stepping stones that propelled him toward greatness.”

Doyoyo is survived by his wife, Thato; two children; three sisters; and three brothers.