Saving Children

One alum’s groundbreaking research has driven global policy change

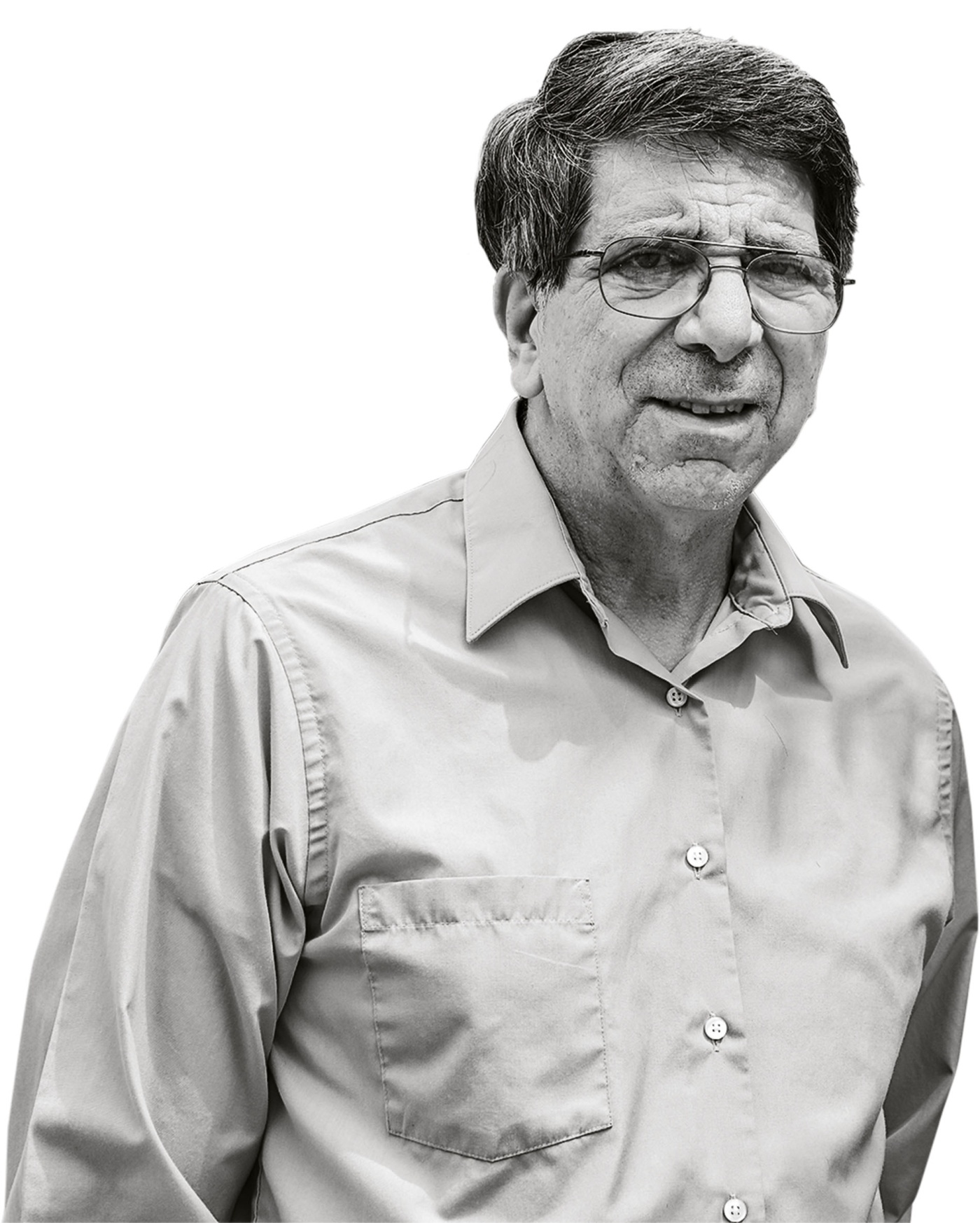

Edward Frongillo ’75 always enjoyed the challenges of gathering scientific data. Early in his career as an ecologist studying a wasp parasite, Frongillo even had to invent his own trap to capture the evasive specimen.

But the former summer camp counselor realized that he cared most about supporting the health needs of children. He now serves as the director of Global Health Initiatives at the University of South Carolina’s Arnold School of Public Health and focuses on qualitative and quantitative analyses of the consequences of food insecurity.

Frongillo’s breakthrough came in the early 1990s, when he and several colleagues quantified for the first time that around half of all child deaths were caused by what he describes as the “synergy between malnutrition and infection.”

“If the children weren’t malnourished, even if they got infected, they wouldn’t have died,” Frongillo says. “That really helped to get nutrition much higher on the global agenda.”

Another multi-year research project from Frongillo studied the health differences between breast- and formula-fed infants, providing a foundation for the World Health Organization’s global guidelines supporting breast feeding for the first six months of a baby’s life to increase IQ and survival rates.

Frongillo’s field research has also studied coping mechanisms of poor households from upstate New York to Venezuela, revealing that even small increases in food insecurity can worsen children’s academic performance and diminish their mental and physical health.

To turn the implications of his research into policies, Frongillo has often had to play diplomat as much as data analyst. While in Vietnam on a World Bank mission to improve investment in nutrition, Frongillo recruited the country’s national soccer team coach as an advocate after seeing him complain in the news that his talented players lost the Asian Cup quarter-final because they were shorter than the competition.

“It’s always about partnering with other people, and finding people who can contribute and making it possible for them to do that,” Frongillo says. He is currently working with three United Nations agencies—World Health Organization, UNICEF, and the Food and Agricultural Organization—to assess diets in a range of developing countries as their food supplies evolve, including studying their growing reliance on cheap but often unhealthy processed meals.

Despite his groundbreaking research, Frongillo says the dozens of undergraduate and doctoral students he has mentored over the decades count as among his most important undertakings.

“A lot [of my impact] has come through training students and helping them develop their talents and make use of their innovative ideas so they can make a contribution,” he says. “And that’s tremendously rewarding.”