Living Large While Something’s Trying to Kill You

Writer and performer Annie Lanzillotto ’86 has spent a lifetime dodging cancer—while making work that elevates her vibrant, violent working-class upbringing to the realm of poetry, ritual, and myth.

On a balmy Tuesday in August in the airy, sleekly contemporary 14th floor waiting room of one of Memorial Sloan Kettering’s Manhattan cancer centers, a thick Bronx accent cut through the hush of patients scrolling their phones, dozing, or gazing out massive windows high over the East River. The accent belonged to writer and performer Annie Lanzillotto ’86, who was talking with outdoor-voice ease about what it felt like to be back at MSK for her third cancer diagnosis in 42 years. The first, for Hodgkin’s lymphoma, had been the fall of her freshman year at Brown in 1981. Then, after brutal treatment involving a surgery that cut her midriff wide open, followed by 16 years of remission, the second, for thyroid cancer, came in 1997. And most recently, after another 25 years of remission, here she was again to discuss what to do about her third diagnosis, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, which came last year.

It wasn’t as if she’d not set foot in one of MSK’s various uptown buildings in all that time, however. Since 1981, doctors there have been seeing her regularly to track the effects of years of radiation, chemo, and surgeries on all parts of her body. She was such a rare case—someone to outlive multiple cancer diagnoses over the course of decades—that she had outlasted many of her doctors, who’d recently retired, and here she was ready to meet a new, younger team for the first time.

“This is my happy place, my safe space,” she declared as she fixed herself a cappuccino at a fancy coffee machine in the waiting room. “I grew up surrounded by violence and trauma and this is the place where I’ve always been cared for and loved, with my own room and bed. I’ve been on a first name basis here for decades with so many doctors, nurses, even the patient aides and the doormen.” (She name-checks them all, as though they are family members, in her 2014 autobiography, L Is for Lion: An Italian Bronx Butch Freedom Memoir.)

She was wearing sunglasses propped up on her cropped hair, an oversize blue cotton shirt, and a fuchsia scarf that partially obscured a neck whose muscles she says have been weakened by radiation. Neuropathy—a common cancer-treatment side effect—has permanently numbed her fingertips, and only the month prior, she’d endured what she estimated was her 30th hospitalization at MSK for pneumonia, a result of a chronically compromised immune system. Yet nothing about her appearance or demeanor betrayed a medical history that was painful to listen to, never mind what it must have been like to actually experience. She was loud, enthusiastic, expansive—the same Annie everyone who’s ever known her has witnessed.

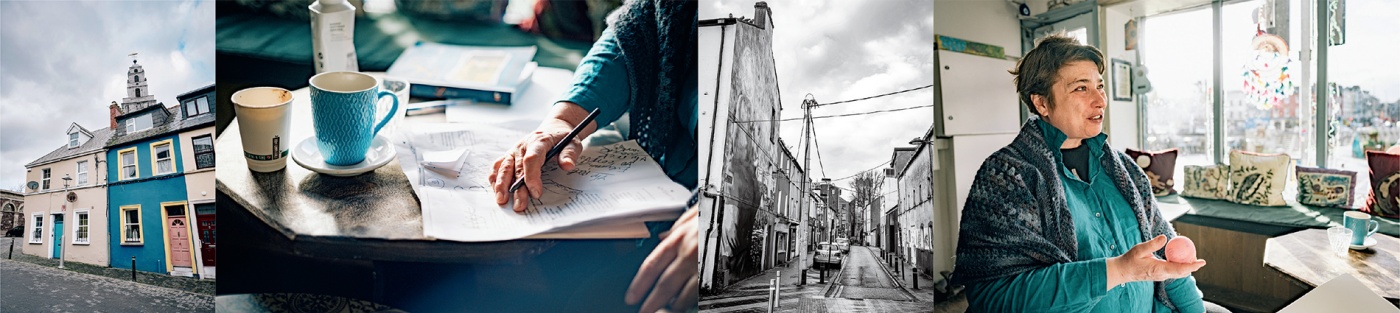

Mostly, it seemed, she wanted to talk about her upcoming trip to Ireland—a country she loves nearly as much as her ancestral homeland of Italy—where she was lined up at a few venues to perform a show she’d written called Spaldeen Ascensions. The show is a funny and accessible metaphysical meditation on “Spaldeens,” Bronx-ese for the Spalding rubber balls she’d spent her childhood throwing up against a wall, sometimes for hours, to escape the house where her father regularly beat her mother.

In her telling, often, “we’d hit them with a broomstick and they’d disappear down a sewer.” (Much of her work involves the everyday fixtures of the all-Italian block she grew up on in the Bronx’s Westchester Square—its stoops, sewers, street lamps, and mailboxes, which she and her friends would mount for hours to gossip, boast, and crack dirty jokes.) “But sometimes we’d hit them into the blinding sky and nobody heard them bounce back down. Where did they go?” She pauses, her warm blue eyes wide. Then, with a fuhgeddaboudit cadence: “It’s a metaphor for the mystery of life.”

Soon enough, she was in an exam room meeting for the first time Dr. Lorenzo Falchi, a young Italian lymphoma specialist who’d become part of her new care team now that the team that had seen her the past 40 years—Dr. Kempin (whom she once persuaded to appear on stage with her), Dr. Straus, Dr. Stover—had all but retired. She gave Falchi copies of her books, including Whaddyacall the Wind?, an intensely vivid collection of poetry and essays about Italy, and she and the doctor instantly started Italia-bonding.

“Ciao, come stai?” she asked. She told him her family hailed from Bari, then inquired where on the boot he was from. Umbria, he answered, just outside Rome.

“Near Amelia?” she asked.

The doctor gasped. “Oh my God, you know it?”

She nodded. “It’s beautiful!”

“Their hospital is at the top of the highest hill!” the doctor marveled.

This, it quickly became clear, was classic Annie: able, effortlessly, to bond with a stranger in seconds—unable, almost, not to strike up a conversation with them. And the ability to create in others the sensation of being with your oldest and best friend, even though you’d met 20 minutes ago. The eyes that crinkled in a smile, the accent that sounded irresistibly like something out of a dozen beloved movies. “I didn’t wanna become a professional Italian,” she said at one point, only half-convincingly, “or a professional patient or a professional lesbian.”

Then the talk moved to what to do with her latest wave of cancer, which had been detected in early 2022, “just as we were coming out of Covid,” she’d noted. “My diagnoses have always come at peak times in my life—the first one at the start of Brown, the second just when I’d had a really big show.”

Her latest scan and labs, the doctor explained, showed, happily, that the cancer appeared not to have progressed since the last round, several months before. That was good news, he explained, because, given her long, hard history of chemo, radiation, and surgeries, the plan and hope was that the cancer would not advance, thereby indefinitely putting off the difficult question of how to treat it, given how many treatments she’d previously had.

“Hopefully this thing’s gonna leave you alone,” the doctor said. “You’ve been through so much.”

He had no idea—including everything that happened even before cancer came into her life.

Lion of the Bronx

Lanzillotto, 60, was born in the Bronx in 1963, the youngest of four siblings—including two brothers and a sister—who were the children of “Lanzi,” a WWII vet who struggled with violent mental illness and PTSD after surviving the brutal invasion of Okinawa, and Rachel, a southern Italian beauty and manicurist who bore the brunt of Lanzi’s brutality until their bitter divorce when Annie was 12. She was also the granddaughter of Rosa Marsico Petruzzelli, a no-bullshit grocery-shopping and cooking machine whose broken English and tough-as-nails survivalism feature heavily in her granddaughter’s work—to the point that Gran’ma received a standing ovation when, garlanded and crowned in garlic bulbs, she appeared in Lanzillotto’s performance work at the Guggenheim Museum in 1996. (She later confessed to her granddaughter that she’d have liked her own performance career, like Whoopi Goldberg, “who was smart—she started young.”)

Lanzillotto’s written and performed work recalls this part-loving, part-vicious Bronx childhood with the vivid intensity of Proust recalling a madeleine—her work is deeply accessible, especially for those not versed in the more arcane side of performance art, because it evokes, in language both limpid and poetic, daily life in this milieu, from her fix-it-man father braying for “Cawwwwfeeee!” upon arrival home from work, to the bubblingly golden perfection of her grandmother’s special-occasion lasagna, to the inner monologue of a brainy but most unladylike tomboy—that would be Annie—out playing ball on the street well past dusk on summer nights.

“From the top of my stoop I watch the boys in all their freedoms, zooming up and down the street, running in and out of passing cars, peeling their T-shirts up over their heads and tucking them in the back of their pants, whipping the air with their mothers’ broomsticks, whacking Spaldeens far over rooftops…” is how one typically cinematic passage begins in L Is for Lion. “I sit on the top step and smell my Spaldeen and dream of the day I’ll be allowed to play in the middle of the street where the big boys play stickball.”

But Lanzillotto describes with equal granularity the chaos of her father’s broken mind and the physical toll it took on her mother, as well as feeling, in her words, “drawn and quartered” when her mother wrenched her away from her father, raising her on welfare in a rental in nearby Yonkers. Precocious and with a flair for public speaking nurtured by a nun teacher, Lanzillotto applied indifferently to Brown at a high school friend’s suggestion and didn’t even understand the fuss when relatives marveled that she’d made it into the Ivy League—that, in her father’s words, “you just got a shot.”

Arriving at Brown the fall of 1981 from a working-class Italian American monoculture, she found the wealth and privilege on campus “confusing—I didn’t understand class at all.” But she was also full of excitement at having escaped a world that, even years before she came out as gay, she understood to be confining. “Brown was an intellectual banquet and I was ready to eat everything,” she says. And she was especially excited to be trying out for Brown’s womens’ basketball team.

That was also her first clue that something was wrong—she felt strangely too weak to make the basket and it was suggested she aim for junior varsity instead. Visiting the Jersey shore, she had her likeness drawn by a boardwalk artist—who, she later noticed, drew a noticeable lump on her neck. Thus began, to make a long story short, her relationship with both cancer and Sloan Kettering, which she entered around the same time that doctors there were increasingly noticing strange purple lesions on the skin of gay men, the mark of the cancer Kaposi’s sarcoma—an early sign of the disease that soon came to be known as AIDS. (She would become obsessed with the contrast between the disease and her own. “I was enraged about the prejudice against AIDS, which made me feel my privilege,” she says. “No one blames you for having cancer. Everyone just wants to help you get well.”)

Slightly more than a grueling year later, during which she not only had massive open-belly surgery to remove a tumor but also went back to Brown and self-administered chemo, she was in remission—and part of a support group of young Rhode Island cancer survivors with whom she became extremely close, including fellow Brown student Peter Findlay ’85. In short order, they all died but her. “I think I went to eleven funerals my sophomore year,” she says. “Those deaths made me feel like I was going to die any minute.”

She didn’t. Instead, at Brown, she thrived, discovering her lesbian identity—“when I was at Sloan Kettering, all the Brown soccer dykes, with their big calves from running up those Providence hills, descended on my bed,” she laughingly recalls—spending a semester in Cairo where she dressed as a man so she could walk the streets unmolested, and creating her own major, “Everything You’ve Always Wanted to Know About Cancer But Were Afraid to Ask.”

“She was a genuine free spirit,” says fellow artist Neil Goldberg ’86, who’s stayed close with Lanzillotto to this day. “I’d be awestruck by the things that flowed from her mouth. She was really different from anyone else on campus—the accent, the realness, her willingness to take risks.”

She considered joining the military, like her father and brother, until geologist Jim Head, one of the many professors she became close with, dissuaded her. She also wanted to apply to med school, she said, until the dean of pre-med dissuaded her of that, telling her, “An applicant in [cancer] remission is not a good four-year investment.” (Part of her long journey with cancer, she says, has been “grieving the loss of career options.”)

Instead, after graduation, she found herself in New York City, where she became a part of the militant late-1980s AIDS activist group ACT UP, dove into the downtown lesbian club and art scene, centered at the time around an edgy venue called the Clit Club, and became enamored of the angry, expressive queer performance art scene that was fueled by the AIDS crisis.

“I saw male performers like Mark Ameen and Ron Athey doing work on stage with their bodies as material,” she says. “Blood, flesh, breaking skin.” But what really inspired her was seeing, in the early ’90s, Bitch! Dyke! Faghag! Whore!, the seminal piece by performance artist Penny Arcade, who shares Lanzillotto’s working-class southern Italian background and tough-talking feminism. “She blew my mind. Her monologues hit me like sermons. I wanted to hear her talk about anything.”

Soon enough, Lanzillotto was performing her own work at downtown venues including Dixon Place, Franklin Furnace, and the Kitchen. She wrote, and then performed—at the Bronx’s profoundly Italian Arthur Avenue food market—How to Cook a Heart, which the New York Times called her “Valentine to the Italian American community of her youth” and her attempt to “build a bridge from the funky downtown avant-garde scene to the real-life labor of butchers and bakers.”

Goldberg remembers seeing My Throwing Arm: This Useless Expertise, an early piece of hers. “One one hand,” he recalls, “it was absolutely brilliant and poetic, but also so plainspoken and accessible. There are so many gratuitous gestures in performance art, and her work was the opposite of that.” He said that when he saw her Guggenheim piece, which began with actual Bronx residents pushing wire-cage wheeled shopping carts and actual Arthur Avenue market vendors hawking their goods, he cried. “It came straight from the streets of New York, full of people who may have never been to the Guggenheim really claiming that space as their own.”

Lanzillotto says she felt profoundly at home in the low-budget but highly charged world of Lower Manhattan stage artists, where the AIDS epidemic was front and center. “There were people on stage who didn’t know if they were going to be alive in a month, which matched where I was at. I had no thought at that time of living past five years.”

Well, she did—despite the 1997 cancer diagnosis, which took out her thyroid—not only continuing to make work and receive grants to support it, but to teach poetry and performance in city schools and cohabitate for more than a decade in Brooklyn’s Park Slope with a girlfriend, Audrey Lauren Kindred, whose twin sister, coincidentally, had gone to Brown. (They broke up years ago but remain close to this day.) Kindred became deeply woven into Lanzillotto’s family, caring for Lanzillotto’s ailing grandmother right alongside her until Rosa Marsico Petruzzelli died at age 100 in 2001.

“My mother came a long way” in terms of accepting her being gay, she says. So did her much older married sister, Rosemarie, whom Lanzillotto calls a constant source of love and support. She can’t say the same for her brothers. One of them, whom she calls CarKey in her memoir (because that’s how she pronounced his name as a toddler), told her that her gayness “skeezed him out.” The other, whom she calls Ant’ny, was enraged that she revealed family secrets in her memoir. They barely talk anymore, she says.

“I broke all the social codes of Italian-American silence,” she admits. “Omertà is not just a Mafia thing. You’re not supposed to talk outside the house about what goes on inside the house.” But she also admits she had a profound need to talk publicly about, above all, the violence her mentally ill father inflicted on her mother—as much to break the larger taboo of speaking about domestic violence and mental illness as to purge her own trauma of witnessing them. She recalls how the judge in family court made her say, before both her parents, whose fault the domestic unrest was.

“Fifty-fifty,” she answered, terrified of betraying her volatile father. Instead, she felt as though she betrayed her mother—and much of her work ever since feels like an attempt to signal her achingly profound love for both her father, who died in 2001 after years in a Long Island group home for the mentally ill, and her mother, who died in 2016 in her arms—at Sloan Kettering, in fact—of heart failure following cancer. (“I’ve gotten a lot of people into Sloan Kettering over the years.”)

Before her father died, she says, she confronted him about his treatment of her mother. “He said, ‘What are you talking about?’—as though I was lying,” she says. Of course she told her mother she’d tried to talk to him. “There was nothing I didn’t share with her,” she says. “And she had empathy for him, too,” she says, because she knew how the war had broken him.

Still, she adds, her parents never talked again after their divorce.

Living in the moment

Back at Sloan Kettering, with Dr. Falchi, she was asked if she would submit to yet another blood draw so they could check her antibodies; if they were low, Falchi said, they could be topped up to hopefully lower her chronic risk of infections. “I’d love you guys to look at my antibodies,” she said gamely, and seemed especially happy when Falchi said they could likely give her an infusion before she traveled to Ireland, to better protect her while abroad.

After the blood draw, she was in her Honda Fit, driving to downtown Manhattan, her old haunt. (She still lives in the Yonkers apartment her mother moved them into after the divorce. She’s also had to limit her earnings all these decades to remain eligible for Medicaid and Medicare.) She wanted to drive down to the East Village’s St. Mark’s Place, past the site of the old Café Sin-é, the Irish music café in front of which she’d once met one of her idols, Sinéad O’Connor, who had just died the week before.

“I loved her so much I gave her the baseball cap right off my head,” she said, pulling over in front of the spot. “I’m gonna get out for a second and do a little libation.” She stood on the sidewalk in front of the doorway and raised her arms in the air, as though she were saluting the goddess Sinéad, drawing glances from passersby. Then she got back in the car, shaking her head. “There should be rose petals all over the street to honor her,” she said.

It was now 1 p.m. “This is when I get tired and usually take a nap, because I don’t have a thyroid,” she said. Plus, she was famished. Still, she couldn’t stop pulling over to point her iPhone camera at elaborately graffitied mailboxes—for a slideshow she was going to incorporate into her Ireland performances about how much mailboxes meant to her. “They only have thin slots now, so they don’t talk to you the way they used to when you opened them,” she lamented. “They used to sound like sea lions.” She then made the rusty yelping sound that an old-fashioned, wide-mouthed mailbox once made.

Finally, she was at a little Lebanese manouche joint in the West Village where her friend N., a cherub-faced young man from Jordan, was working behind the counter. He was a gay refugee whom she’d met when he was pumping gas in Yonkers. She took him in for nearly a year, introduced him to her queer downtown performer friends, helped him apply (successfully) for asylum and urged him (successfully) to get his New York State barber’s license—“so you can make something out of yourself,” she told him.

N. nearly cried, he was so happy to see her. “Annie, I love you!” he cried, setting down salad, kibbe, and labneh in front of her. He said she was the first person he’d come out to.

“I thought he was straight because he was always talking about needing a wife!” she laughed. (Only for green card purposes, N. clarified.)

While she ate, she mused about her relationship to time. “Did you notice how I can never remember when anything happened?” she asked. “That’s because I live solely in the present. Maybe not as much as a dog or a baby, but—” she paused. “If you’re the kind of person who puts your dreams off, like, oh, ‘I’ll do that after I divorce, after my kids are grown up, after I lose weight, after I save money,’ then you’re not the friend for me. I’ve never had that luxury. And my father didn’t raise me that way. His mentality was that a kamikaze could come down right now and you die in a heartbeat.”

But she doesn’t want to be anybody’s font of plucky cancer-survivor wisdom either. “I’ve dealt with depression on and off my whole life. The big abyss deep inside me. I’ve had a lot of ghosts.” The last of several times that day, she mentioned all the young people from her Brown-era cancer support group whom she, improbably, had survived. “I’ve got a lot of ghosts in my head talking to me,” she said.

“But mostly,” she added, “They say to me, ‘Annie—just keep going for it.’”

More about Annie’s work at annielanzillotto.com. Tim Murphy ’91 is a freelance journalist and author of the novels Christodora, Correspondents, and Speech Team. Reach him at [email protected].