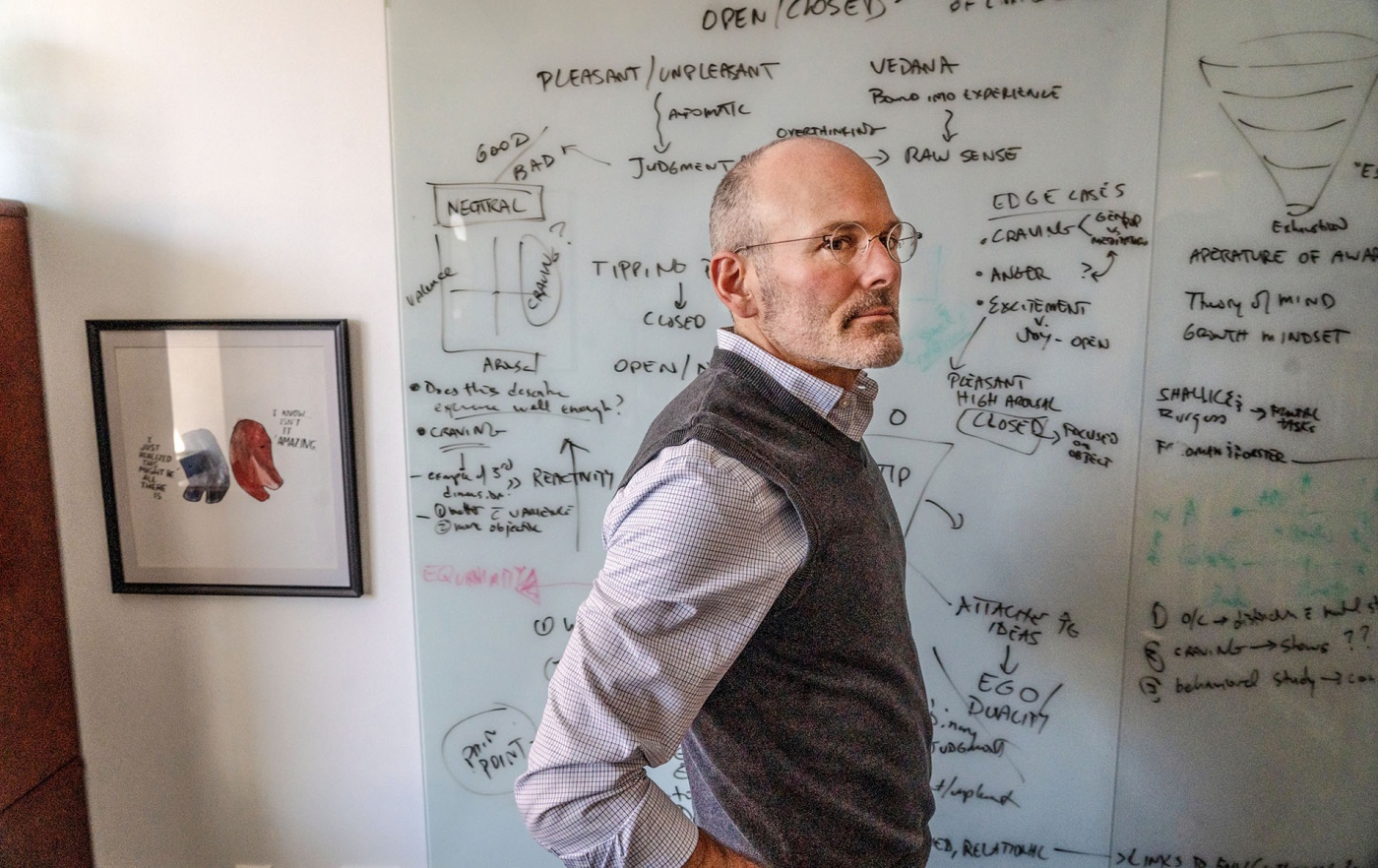

Jud Brewer, director of research and innovation for Brown’s Mindfulness Center, had just finished teaching his favorite class—The Craving Mind, a course on habit change—and was walking along South Main when a car pulled up next to him.

“Hey, Dr. Jud!” Max, a man in his 40s, called out. Brewer did a double take. Max* was a patient at his outpatient psychiatric practice, in treatment for lifelong anxiety plus new, crippling panic attacks triggered by new thoughts while driving like, “I’m in a speeding bullet hurtling down the highway.” Soon, he’d stopped driving almost entirely.

Yet here he was, behind the wheel. What came out of Max’s mouth next was even more surprising: “I’m an Uber driver now!”

How does someone with paralyzing car-crash anxiety become a rideshare driver? The answer lies in Brewer’s decades-long dive into the what, why, and how of mental health, and a groundbreaking approach at the intersection between mindfulness, emotional regulation, and behavior change.

It all started with an upset stomach

The jointly appointed professor (psychiatry at the Warren Alpert Medical School; behavioral and social sciences at the School of Public Health) has firsthand experience with anxiety’s grip on both body and mind. When he learned early in his MD/PhD program at Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, that irritable bowel syndrome—which he’d endured for years—is catalyzed by stress, “I started meditating,” Brewer recalls, “and my symptoms went away. I thought, ‘Wow, that’s pretty cool’...and realized I had no idea how my mind worked.”

As a psychiatry resident at Yale, Brewer specialized in addiction issues, weaving mindfulness—still under Western medicine’s radar in the early aughts—into his treatment approach. He was the first to pit the then-gold-standard treatment for smoking cessation (stress reduction and behavior modification) against mindfulness training (MT), which involved mapping out one’s smoking triggers; accepting cravings without self-judgment; and meditation. Quit rates, he says, were five times higher in the MT group.

Next, Brewer and his colleagues tackled another common addiction, habitual overeating, yielding a 40 percent reduction in food cravings.

Unwinding anxiety

In 2018, Brewer took on anxiety disorders, which affect one in three Americans.

Brewer posited that just as people self-soothe with tobacco or sweets, the act of worrying can itself become a maladaptive behavior on which the brain becomes hooked. “The feeling of anxiety triggers the mental behavior of worrying, which gives people a false sense of control,” he says, “and that's rewarding enough that the brain says, ‘Oh! The next time you’re anxious, you should worry.’” The result: worrying becomes a habit.

But habits can be broken. Not with willpower—that part of the brain “goes offline when people get anxious”—but with mindfulness.

First, he says, “You need to recognize you’re stuck in an anxiety loop. Second, get curious: ‘How is obsessing over car accidents helping me?’” This grounds you in the present moment—the essence of mindfulness—and brings the logical parts of your brain back online so you realize worrying isn’t accomplishing anything. With practice, the loop shatters.

Brewer has written three books, including the bestseller Unwinding Anxiety: New Science Shows How to Break the Cycles of Worry and Fear to Heal Your Mind, plus an Unwinding Anxiety app which, in a randomized controlled trial, cut anxiety for generalized anxiety disorder sufferers by 67 percent after two months. Even Brewer was stunned. “Here we are, tremendously improving people’s lives…through an app!”

As for Max, he knows that most drives end safely, and while panicky thoughts theoretically prevent accidents (by limiting driving), they also impeded his ability to work, see friends, and enjoy life. Unwinding his anxiety put Max back in the driver’s seat.

*His name has been changed to protect his privacy.