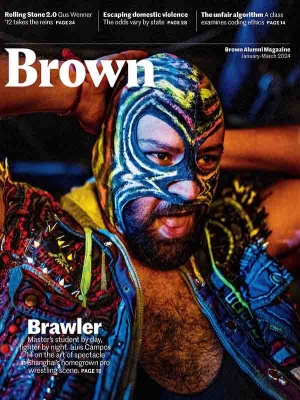

Cover of the Rolling Stone

Gus Wenner ’12 has a fresh take on his dad’s 1967 hit. Will it play for Gen Z and beyond?

Gus Wenner’s life has always had a soundtrack.

The Rolling Stone CEO and son of the magazine’s founder grew up between New York City and Idaho, in homes where his mother’s vinyl played late into the night, every night.

“I would wake up in the middle of the night to go get water and in the hallways and the living room, records would still be playing,” Wenner recalls. “Van Morrison, Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry, Sam Cooke—at a really young age, those were seeping in everywhere.”

A childhood soaked with the classics prepared him well to take over the magazine from his father, Jann Wenner, who cofounded the iconic music publication in San Francisco at 21, a year after dropping out of UC Berkeley. The younger Wenner, who similarly took the helm in his twenties, carries nostalgia for the rough and tumble rock ’n’ roll climate that birthed Rolling Stone but spends little time mourning a past that fuels his future. Meanwhile, for his father, the magazine is a relic of a bygone era, a souvenir he admitted he doesn’t read “that much” anymore.

“It’s about people I’m not personally interested in. I don’t really care for K-pop. I don’t really know who Cardi B is,” Jann Wenner said in an interview with the New York Times about his memoir, released last year. But he conceded that his son “sold and saved the magazine. … I could never have done it.”

On this, both Wenners agree. In 2021, the magazine saw its most profitable year in two decades, a success which Edward Augustus (“Gus”) Wenner says he can replicate only by adapting to the times.

“I truly believe we will have a president in the next 10 to 20 years who is going to be vlogging, maybe even sooner,” Wenner predicts. “These themes—technology, social media, creators—are so critical, and it’s very important to me that we are at the bleeding edge of that and applying the same standard and brand of journalism to it that we do anything else.”

Growing up groovin’

On principle, Wenner is reluctant to name-drop celebrities, but the music magnate did acknowledge regularly brushing shoulders with the greats throughout his childhood. A day spent with Bob Dylan when he was eight or nine years old stands out as one favorite memory.

“I was able to relate with him on a very pure level because I was too young to really know” how famous he was, Wenner says.

Indie-rock band and fellow New York City natives the Strokes were a must for middle and high school, followed by a love of country music that served to influence Wenner’s own performances in college.

At Brown, in between writing chapters of a (still unpublished) novel, Wenner formed a musical duo with another celebrity kid and childhood friend, Scout LaRue Willis ’13, daughter of actors Demi Moore and Bruce Willis. But Wenner’s heart for music was evident even on the nights he wasn’t honing his indie-folk-country-rock sound.

Laughing, he remembers the days when it was possible to win first pick in Brown’s housing lottery by submitting a video; he and his friends entered with a music video sophomore year and scored a beautiful suite in Slater—a notable upgrade, he adds, from Perkins his freshman year, “which everyone has something to say about.”

After building a sizable following in Canada and dropping an eponymous EP the summer after graduation, Gus + Scout were poised to make the transition from small-scale stardom to national notoriety. Instead, that fall Willis returned to Brown for her senior year while Wenner took anentry-level job at Rolling Stone—“if it even had a title, it was very lowly”—and fell for the family business.

Keys to the kingdom

“Just so you know, this is going nowhere,” Wenner recalls his father saying one of the first days on the job.

The potentially devastating blow hardly fazed Wenner, who replied: “I know. I don’t want it to. I just want to learn for a year and then move on.”

With two older brothers busy in successful careers as a photographer and a beer brewer, respectively, Wenner felt little expectation to take over the magazine. But at a time when print was beginning to crumple beneath the weight of the digital wave, Wenner possessed a unique ability to peek into the minds of the next generation and meet the moment.

Wenner carries nostalgia for the rough and tumble rock ’n’ roll climate that birthed Rolling Stone but spends little time mourning a past that fuels his future.

“In those early years, I was able to really create some progress around growing the digital piece of the company,” Wenner recalls. “When I came in there were maybe 3 or 4 million visitors coming to RollingStone.com a month, and by the end of year three, I think we were up around 15 or 20 million.”

In those three years, Wenner’s career made several significant leaps forward, when his father catapulted him first to website director in 2013—after less than a year on the job—and again in 2014, when he was promoted to digital head of the company. At the time, the rapid promotion cycle sparked both internal and external criticism, with many journalists decrying what seemed to be a blatant act of nepotism.

Former Rolling Stone managing editor Will Dana told The Fine Print last year that when Wenner first started as an intern in 2007, “let’s just say people all knew that there was a better chance they’d end up working for Jann’s kid than Bruce Springsteen’s son or Kurt Cobain’s daughter, other interns from around that time.”

For his part, Wenner doesn’t deny that family connections helped him obtain such a prominent position at an early age.

“When I was shadowing the chief digital officer… one of the really early pieces of value I was able to add was to foster his ideas, because I had my dad’s ear,” Wenner says. “I was young and I was just learning, but I was able to cut through the [red tape] and make things happen just by nature of proximity.”

But to any allegations that nepotism has weakened the company or made it any less of a leading voice on music and youth culture, Wenner says the proof is “in the pudding.”

“In any industry, if you get your foot in the door, you still have to walk through it… and especially for publishing and print media, it was not a forgiving place,” Wenner says. “The bottom line was always that if we were able to show gains and results and make that transition [to digital], then let’s do it. And we did.”

On the shoulders of giants

But in 2017, “for lack of a better word, shit got real,” Wenner says. Rolling Stone went up for sale amid a mountain of debt, and Wenner’s father suffered a major heart attack, leaving the fate of the company in his son’s hands.

“It was all in the papers every day. I was selling things and solving corporate dilemmas and managing the employees’ mindset and their questions about what was going to happen, all the while being there for my dad in the hospital,” Wenner remembers. “That was when the future of the company—and more importantly of Rolling Stone—really fell on my shoulders.”

As president and COO, Wenner was forced to abandon plans to grow Rolling Stone Country and its accompanying Nashville office; instead, the company sold sibling publications Us Weekly and Men’s Journal in 2017 and sold Rolling Stone less than two years later to its current parent company, Penske Media Corporation.

While the literary arts major and folk rock band guitarist did not join the business particularly well-equipped to navigate the financial precarity of the post-recession media industry, he rose to the challenge, steering the magazine away from economic collapse into a new era of growth. But the passing of the torch was not without a few bumps in the road.

“If you get your foot in the door, you still have to walk through it… and especially for publishing, it was not a forgiving place.”

In Jann Wenner’s memoir, Like a Rolling Stone, he says of the transition: “Of course, I was now in my seventies, standing in the way of progress, stubbornly locked in my office listening, it was assumed, to Bob Dylan and Neil Young. I was not invited to meetings.”

“I wanted to remain with Rolling Stone, to have some relationship with my baby. Could I be the uncle? The grandpa? The brother-in-law?” he wrote. “Nope, I would be the ex-wife. Gus wanted to take over. He listened to me with respect but impatience.”

Anyone familiar with the Wenners can spot the difference between the business styles of father and son or, more precisely, between the generations they seek to capture and entertain. While Jann Wenner frequently scribbled his early stories on the come-down from drug-fueled interviews and carried his affection for LSD well into his 70s, his protegé is far more likely to be found in the boardroom in a crisp button-down, indistinguishable from the young execs of the startup scene.

The elder Wenner similarly finds today’s music—which he called “driven by teenage girls”—largely divorced from politics and social movement. His son disagrees and says he regularly finds inspiration in the magazine’s origin story for cutting-edge commentary on today’s culture.

“Those songs, at that time, they meant so much more than just sound. It was about a political message, it was about a clash with the prior generation. Being able to draw on that purview has given us a wide berth in terms of covering entertainment and culture, in addition to music,” Wenner says.

“If you look at our coverage, we’ve done incredible pieces about technology, we’ve started to cover social media, which in my opinion is one of the most interesting stories of our time… I mean, we literally had [YouTuber] MrBeast on the cover,” Wenner continues. “That was a big statement: that we’re here, or we’re trying to be.”

Big wheels keep on turning

“I’m very sensitive to not watering down the brand or compromising the mission,” Wenner says as he mulls over his vision of expanding what he calls “the Bible for young people” from a commodity into an experience.

Last February, Rolling Stone bought a majority stake in Las Vegas art and music festival Life is Beautiful, which the media mogul says he hopes to expand to other cities in the coming years. And while Wenner remains fairly tight-lipped about other big plans, he hinted that Rolling Stone concert halls and even hotels could be in the works sometime soon.

“The content has to really be future-forward, and sometimes that means being very classic and timeless in the approach,” Wenner explains. “So yes, we are open to physical assets and potentially hotels or venues or whatever, but it really has to fit with our vibe… If we’re going to do an amphitheater, I want it to mean something to people, which is where we started, and not just be a physical structure. That’s not easy to do, but it’s what we’re trying to do.”

Though redefining the family business has been bittersweet, Wenner says securing the future of the magazine was always his top priority. The responsibility is one he has never squandered or taken for granted, not only because of his personal connection to music but also out of a deep love and respect for his father.

“When I stepped into the role of running digital across the company and we were thinking about succession planning and whatnot, [my dad] said to me, ‘Nothing would make me prouder than having my baby in the hands of my baby,’” he remembers. “That was really beautiful, so you have to understand that the weight and meaning behind it all was a really powerful force for me.”

Whether launching a new festival location or building a music venue, Wenner is unwavering in his belief that the core of Rolling Stone will always remain “great journalism.”

“That really is the way to remain relevant,” he says. “Now, the way we produce and think about journalism is very different, but the idea of an iconic image, a great story, hasn’t changed. Great stories are always what move the world.”

Ivy Scott ’21.5, a CASE and Eddie award–winning former BAM intern, is a criminal justice reporter at the Boston Globe.