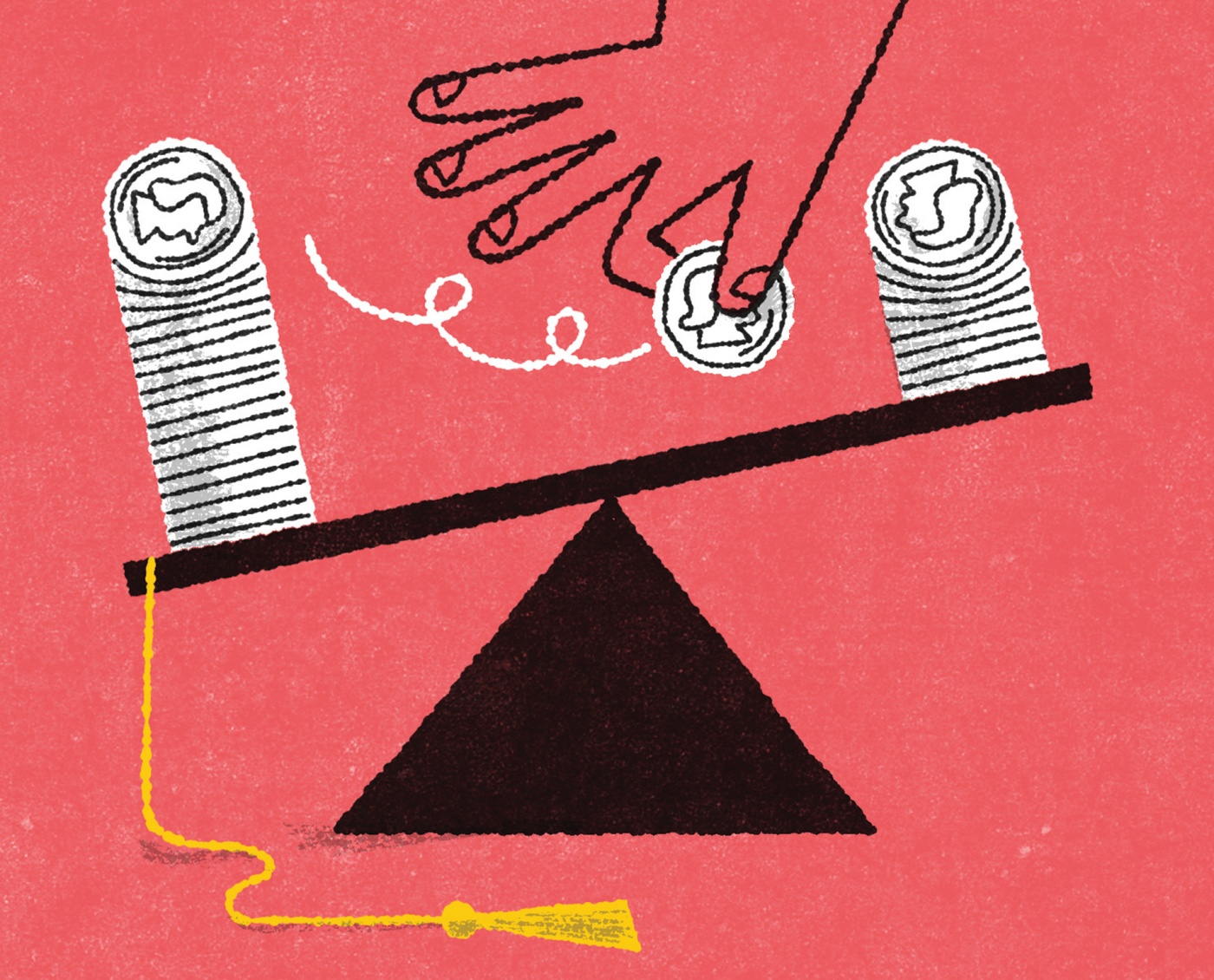

Town and Gown

Brown boosts voluntary payments to the city of Providence

Brown will almost double the direct payments it makes to its host city, from $6.5 million to more than $11 million annually, beginning in the fall of 2023. The October agreement came after years of negotiation and amidst a national push for higher education institutions to increase what are often called payments in lieu of taxes (PILOT).

“It was a highly collegial and collaborative process,” says Russell Carey, Brown’s executive vice president for planning and policy, about the PILOT negotiation process. That’s in large part because of positive impacts that Brown has on Providence and the state economy, he notes, from work in the city’s struggling public schools and support for unionized labor to its status as an economic engine—Brown is one of the state’s largest employers and a major purchaser of local goods and services. “There is a web and a network of economic, social, cultural, and educational impacts that the University has on the community that are positive,” he says.

New language in the agreements, Carey adds, would incentivize Brown to return property to commercial use in a way that would help generate long-term revenue streams for the city.

“Speaking as a student, I think Brown could have done a lot more,” said Niyanta Nepal ’25, a concentrator in biomedical engineering and education from Concord, New Hampshire. Nepal is one of the copresidents of Students for Educational Equity, or SEE, a student group on campus that advocates for equity for Providence public schools—which are in such dire straits that they are in the midst of a years-long state takeover. SEE is one of the leading members of the Brown Activist Coalition, a smorgasbord of student groups that advocated for University administrators to increase the amount the University pays to the city of Providence to at least $15 million per year, along with other demands such as making the University’s libraries open to local residents.

It’s part of a national debate about the role of wealthy institutions in cash-strapped municipalities. In 2021, Yale made headlines when it upped its payments to New Haven—already among the highest in the country at $13 million a year—by adding an additional $10 million a year. In Providence, the presence of nonprofits such as hospitals and higher-ed institutions means nearly 40 percent of Providence properties are not taxed, making it hard for the city to address its financial ills, including unfunded pension liabilities reaching over $1 billion in 2023.

Some alumni politicians say the University’s large endowment—which topped $6.6 billion in 2023—and its position as one of the largest property owners mean it could do more. According to a city report from 2022, the University would owe over $49 million in property taxes each year if it didn’t qualify for nonprofit status.

“I think the agreements are woefully insufficient, and it’s disappointing that the city did not try and get more,” says Sam Bell ’16 PhD, a state senator in Providence who has been outspoken about the deficiencies of the new PILOT agreement. Local state representative David Morales MPA ’19 has even proposed legislation that would tax the University’s endowment.

“As an alumnus of Brown, I was able to witness firsthand the amount of resources that institution has to offer,” Morales says.

With negotiations over, student engagement with the city will continue, vows Nepal. “Now more than ever there will be focus on how to make sure Brown is giving back,” she says.