In the fall of 1985, Michael Antonucci ’88 ambled into Michael S. Harper’s literary arts seminar, cigarette dangling from his lips. “Put that out, I’m an asthmatic,” Harper said. “Who are you, where are you from, and why are you here?”

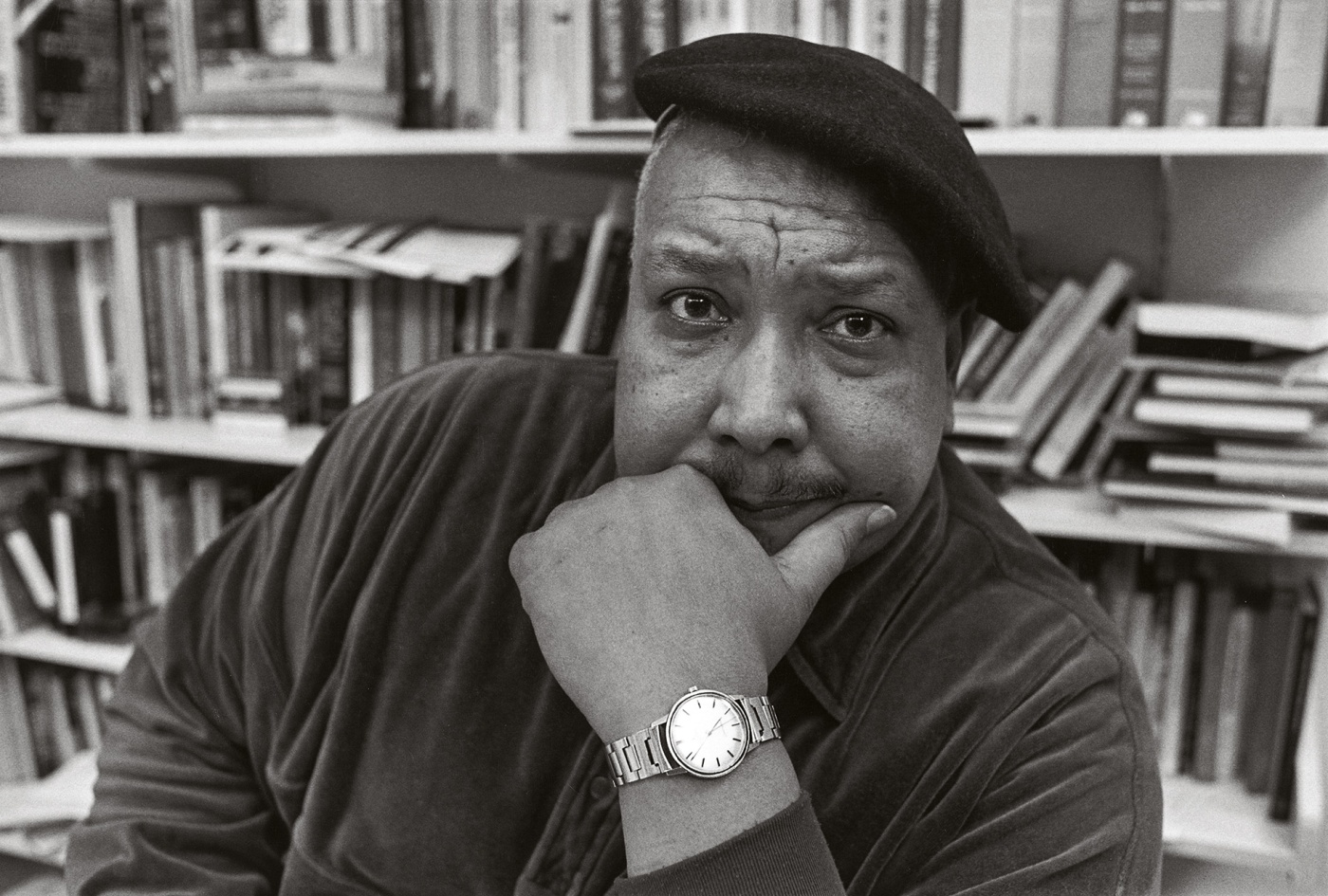

Today Antonucci, who entered Brown planning to study history, has just published Understanding Michael S. Harper. It is the first scholarly monograph on the man who transformed Antonucci’s life and the lives of 43 years’ worth of Brown literary arts students. With it, Antonucci hopes to honor Harper’s remarkable career and shed new light on his notoriously complex poetic project.

Within the poetry community, Harper was a meteoric success of the early 1970s. Before that, he was relatively unknown, teaching English at a series of smaller colleges. In 1968, he submitted his first full volume of poetry to the U.S. Poetry Prize Competition. He lost, but came home with a letter from judge Gwendolyn Brooks that said he had been her clear winner. The collection he submitted, Dear John, Dear Coltrane, was published shortly after.

Brooks was right—America was ready for Dear John, Dear Coltrane. Harper’s poems hold unwritten Black history to light, champion an expansive sense of kinship, and celebrate the power of Black music. The first volume arrived on the heels of the civil rights movement, and the public embraced Harper’s humanizing portrait of Black America. So did Brown. Reeling from the 1968 walkout of three-quarters of Black students, the University was making racial diversity an institutional priority. Harper became one of Brown's first Black full professors. The esteemed poet who lionized Black pioneers in his work had become part of such history himself.

For all the awards and acclaim that followed—among them a Guggenheim fellowship, a Melville Cane Award, five honorary doctorates, the first Rhode Island poet laureateship, and a spot on a Pulitzer judge committee—Harper is what Antonucci calls a “well-known unknown.” Before now, not one person attempted an inclusive analysis of Harper’s full body of work. Scholars including John Callahan, Michael G. Cooke, and Robert Stepto long identified the importance of Black music, kinship, and history in Harper’s poetry. Antonucci’s new effort modifies and contextualizes previous analyses while pushing them into the public eye.

The book seeks to deconstruct common barriers to understanding Harper. Antonucci coins the terms “generative kinship” and “convergent history” to speak to Harper’s poetic goals. The book is packed with references to niche concepts like “modality” and “the Territory,” but we are hand-held through the major themes.

Armed with this help, a dive into Harper’s world is rewarding. His poems put people of color back into the American historical narrative. He paints a vivid picture of both the suffering and joy of Black Americans at moments in our nation’s history—acts of witnessing that invite his readers to expand their conceptions of the past.

“He could sort the present, he knew where it came from, and he knew where it was going,” says Antonucci. Though Harper passed away in 2016, the poems he left behind offer wisdom about our present and future to those who are willing to look for it.