The Art of Spectacle

Luis Campos ’14 gets real with his research into combat sports as a pro wrestler in Shanghai.

When Little Johnny enters the wrestling ring, grown men tremble, flowers wilt, and opponents are reminded why they paid a premium for life insurance.

One night in early June, the six-foot-seven, 330-pound man wrapped in a spandex singlet lumbers into the arena to defend his Jade Warrior championship title in Middle Kingdom Wrestling’s showdown in Shanghai.

Horror movie music booms as a screen behind the ring shows footage of Little Johnny slamming challengers to the floor like swatted flies. He’s beaten Bamboo Crusher, Mad Tiger, and even Steve the ESL Teacher in bouts for Middle Kingdom Wrestling, one of China’s emerging professional leagues. His latest opponent, a lithe former mixed martial arts fighter called the Kyote, called his daughter beforehand to tell her he loved her.

The internet wrestling database CAGEMATCH describes Little Johnny’s style as “powerhouse” and “brawler” and notes his signature move is “the corner slingshot splash.” He once broke a man’s sternum doing it.

Soon after the match begins, the Kyote leaps at Little Johnny in a bear hug, only to be caught, lifted, and hurled to the ground with a resonant thud. As the Kyote lies in agony, Little Johnny ascends the ropes, flexes his muscles, and launches himself into a belly-first dive on top of his broken opponent, then places his foot on the poor man’s neck as the Kyote squirms and the crowd gasps.

Outside the ring, Little Johnny’s alter ego, 34-year-old Luis Campos ’14, is a comparatively gentle soul. He completed a master’s degree in public administration from Shanghai Jiao Tong University last year and enjoys sewing and designing his own wrestling outfits. He met his wife, Nini, an optical engineer, after she asked him to make an emoji sticker of her cat, Pangzi; they married just days before the championship match. While Nini admits she was initially wary, she realized Campos was perhaps not a brutish monster when they met on their first date at a Shanghai mall and he showed up in a stylish quilted denim jacket he had designed himself.

Little Johnny’s style is described as “powerhouse” and “brawler” and his signature move is “the corner slingshot splash.” He once broke a man’s sternum doing it.

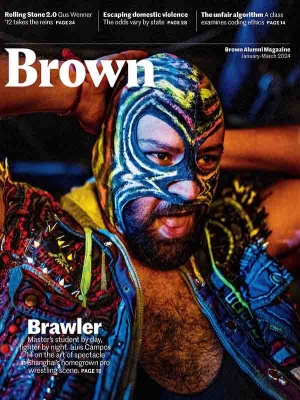

That flair for fashion is part of Little Johnny’s aesthetic. A closer look at his accoutrements reveals Campos’s eye for detail. Little Johnny sometimes sports a Dickies vest customized with festive colors streaked across by hand, the words “Bad Hombre” surrounded by sewn-on spikes, and a donut-like shoulder patch depicting a bright pink anus. For extra terror, Little Johnny occasionally dons a handcrafted Dia de Los Muertos–themed skull mask complete with bared teeth and long slinking hair.

The character is the product of more than a decade of scholarship into the art of spectacle by Campos, whose fascination with why people watch combat sports has taken him from ancient coliseums to Lucha Libre training schools and eventually into the ring as a professional wrestler himself, learning to combine fighting prowess with storytelling and choreographed performance. Most recently, he has been Middle Kingdom Wrestling’s resident “Big Man” and notorious bad guy. Behind the scenes, however, he’s a mentor for inexperienced wrestlers dreaming of stardom.

Before he found himself in front of a sold-out Shanghai crowd eager to see if he would snuff out the Kyote, Campos had carefully rehearsed a convincing ass-kicking following a lesson once whispered to him by a Lucha Libre fighter: “The job of a professional wrestler is to lie and make people believe you.”

A Sport as Old as We Are

As a kid growing up in Guadalajara, Mexico, Campos played with his Lucha Libre figurines until the cheap paint rubbed off the plastic. He was in awe of TV legends like Blue Panther and Atlantis, men who never took their masks off in public.

Campos later moved to Los Angeles and, once at Brown, studied classics, intrigued by the human fascination with watching fights—alongside running, fighting may well have been the world’s first sport—and the evolving role of performative violence in different societies.

“Combat sports are a mirror that reflects a culture’s ideals, because they are a story that cultures ‘tell themselves about themselves,’” Campos wrote in his classics thesis on the history of combat sports. “A study of the recurring changes in combat sports is central towards understanding some of the ways that humankind’s social ideals have oscillated throughout time.”

The extent of the violence of each era’s staged combat was a function of its cultural norms, he notes. Early combat sports were intertwined with funeral rites, preparation for real combat, or an outlet for young men in times of peace.

Ancient spectacles like Roman gladiator matches may have been brutal, says Campos, but in some ways weren’t too far removed from modern wrestling. He considers professional gladiators performers, but with high stakes—the longevity of their careers, and even their lives, depended on their ability to entertain the masses.

Unlike prisoners or enslaved captives who were forced into combat, professional gladiators received years of training paid for by promoters and high-quality medical care to heal broken bones and other injuries. They appear to have given each other bloody cuts to enthrall audiences just as luchadors dove off ropes for exaggerated takedowns, discreetly breaking their falls to lessen the impact on opponents. Like the acrobatics of Lucha Libre, professional gladiator combat was often a collaborative effort between fighters, Campos says.

Not content to study combat sports from the confines of textbooks, Campos took a gap year in 2010 midway through Brown and enrolled as a student at Guadalajara’s La Escuela de Lucha Libre el Diablo Velasco.

“Combat sports are a mirror that reflects a culture’s ideals, because they are a story that cultures ‘tell themselves about themselves.’”

There aspiring luchadors learned tumbling and rolling, strengthened their necks (“the neck is the most important part of wrestling—if you have a weak neck you can get paralyzed,” Campos says), and practiced grappling using

Greco-Roman wrestling moves, overseen by a washed up veteran known as El Satánico.

“There are a lot of bad guys out there who will try to hurt you. You need to be able to fight for real,” El Satánico would growl. “If you are a professional wrestler, you will wrestle people who you don’t know—and you’re never sure who you’re gonna have pissed off.”

After receiving a fellowship through the Brown International Scholars Program, Campos moved to Buenos Aires for a semester in 2013 to train in “catch” wrestling, Argentina’s version of Lucha Libre, and returned in 2016 on a Fulbright to study the cultural imprint of the famed wrestling program Titanes en el Ring, a light-hearted TV show featuring legends like the Red Knight and the Mummy (a fully wrapped character). The show’s popularity peaked during the 1976-1983 military dictatorship, when as many as 30,000 alleged left-wing dissidents were taken by government death squads.

“The government had almost complete control but allowed this product [Titanes en el Ring] on TV. It was interesting that it could exist as something pure in contrast to something so horrible,” Campos says. “Wrestling kind of got left alone and was allowed to do subversive things.”

In Argentina, a grizzled Bolivian trainer dubbed Campos with his wrestling name: Pequeño Juan. In public matches, Little Johnny was voted second best foreign wrestler of the year by one fan site.

He paused his wrestling career during a stint as a Peace Corps volunteer living in the steppes of northern Mongolia (where the president at the time was a former pro wrestler); afterwards, Campos wanted to stay in Asia and moved to the southern Chinese city of Shenzhen in 2019 to work as a freelance writer and marketing consultant.

“I really enjoyed the way that Mongolia challenged me in terms of language and food and culture,” Campos says. “I was looking for something outside my comfort zone. Being uncomfortable has allowed me to grow in a lot of spaces.”

Building a Name in Shanghai

Soon after settling in China, Campos reached out to the promoter of Middle Kingdom Wrestling, an American named Adrian Gomez. He told Campos he could come and help set up a show and seemed surprised when Campos did just that. Impressed by Campos’s commitment and physique—and by his investment in community-building, which included organizing a Shanghai-based wrestler training program—Gomez brought Campos on for more.

“There’s a tendency for foreigners in Asian countries to gravitate toward each other,” Gomez says. “But Luis really connected with the Chinese wrestlers. That helped him get a lot of trust.”

Though professional wrestling remains a fringe sport in China, several leagues are on the rise. Arriving at this frontier, Campos eventually landed a spot on Middle Kingdom’s wrestling web series. His most popular match had 600,000 viewers watching live on social media.

Little Johnny also landed a gig moonlighting twice a week at a bar called Punch Cage while Campos took classes for his master’s in public administration by day. Enduring slams into the rock-hard floor and avoiding the concrete pillars when getting thrown into the chain link cage fence, Campos nonetheless enjoyed his bouts—often against the same 20-something Chinese opponent, a man hell-bent on pursuing wrestling as his full-time profession—and they’d take turns winning or losing based on their moods.

Wrestling builds on stories that may extend across multiple matches and years. Many matches have a clearly defined villain and “baby face” hero.

“The amount of pain we are willing to put ourselves through depended on the crowd,” remembers Campos, laughing.

He was still trying to finish his thesis on government efforts to reduce black market education services, and had been dating Nini only a few months, when Shanghai went into full Covid lockdown in March 2022. Having escaped from his dorm room when the university closed, Campos was stranded inside Nini’s tiny apartment for four months, mostly unable to go outside. They played video games and worked and studied remotely, and each afternoon Campos prepared the government-issued vegetable rations for himself and Nini’s housemates. Nini—who disdains vegetables except for garlic, which she considers “an ingredient”—cooked the meat or woke before 6 a.m. to secure orders of KFC and other luxuries before the city’s entire online food and grocery services were out of stock by 7 a.m. By the time the lockdown was lifted, they were ready to sign a lease together.

“That was the catalyst of our relationship: We had to be locked down together for 90 days,” Campos recalls. “When you are in a relationship, sometimes you feel things should be grand and exciting but it’s really, can you be with the person when you are bored.”

Training Time

You can tell a true fighter by their ears, warped from years of blows, Campos says at a mixed martial arts (MMA) gym on the outskirts of Shanghai in early June.

He’s wearing Crocs and a spiked, donut-themed baseball cap with a bite taken out of the brim (he made it himself); when a Mongolian heavy metal song comes on the gym’s speakers, he translates the lyrics.

Campos and the Kyote are meeting to practice their routine, one of more than half a dozen matches in Middle Kingdom Wrestling’s inaugural Shanghai show the following evening, and the latest step in a years-long effort to make professional wrestling big in China.

The two are advised by an Atlanta native with the wrestling nom-de-ring Zombie Dragon.

“People back home already understand what pro wrestling is whether they like it or not,” Zombie Dragon says. “Here, we’re introducing people to wrestling so we have a harder job, we got to make fans out of people who don’t even know what it is. But everybody understands a kick to the face; things like that really, like, pump up the crowd.”

Wrestling builds on stories that may extend across multiple matches and years. Moves must adhere to a logic often built on physical and character-driven tropes: Little Johnny should appear massively strong, able to lift the Kyote, but brutishly slow and uncoordinated; in contrast, the Kyote should be quicker. Many matches have a clearly defined villain and “baby face” hero.

“Little Johnny is always gonna be the bad guy,” Zombie Dragon says. “As soon as he walks out of the curtain, they know he’s a bad guy, because he’s so freaking big.”

The gym belongs to the Kyote, a former punk rocker with ears like mottled cauliflower who makes a living as an MMA trainer and at the moment is throttling an opponent in the octagon. A wall displays the Kyote’s numerous MMA trophies, belts, and match mementoes. For all his success, the Kyote—now pushing 40 with a kid—is eager to try out wrestling and brimming with ideas for gags. He’s planning to wear a red mask in honor of his Polish heritage. But he hasn’t quite learned how to undo decades of training and switch to fake-hurting people.

Campos watches the Kyote’s sparring partner flail in a chokehold. “He just gets into it,” Campos observes warily. “He knows how to make it look real—because it is real!”

“In a [wrestling] match, we’re trying to help each other,” the Kyote later concedes. “I’m still having trouble grasping that each move is about feeding what I’m supposed to be doing next.”

Intended to seem like a real fight, most professional matches are choreographed sequences, using wrestling’s unique language—moves such as Vader bombs, rope breaks, ax handles, buckles, chops, whips, sunset flips, and the fireman’s carry—to form a narrative. The “Boston crab” is a term for squatting on someone’s back while pulling up their legs in each arm to torque their back, a move with roots in real wrestling, while a “splash” involves leaping belly-first with full body weight onto an opponent. The pain tolerance required is considerable.

Small tricks allow for fluid transitions—good wrestlers typically keep their left foot back when put in a headlock to make it easier for them to get hurled across a room, and often come at each other from the left side so that the attacker can use their right arm to deliver a stronger and more believable assault. There’s even a special “international” sequence ready for two opponents who lack a common language or have never practiced together to perform on the spot.

“I enjoy putting together matches,” Campos says. “Maybe that’s something about wrestling that a lot of people wouldn’t understand, this ability to be creative. There’s elements of choreography and dance and theater, to draw in an audience and use your body and arrange things in an order that makes sense.”

In fact, he concludes: “What I’m doing is evoking responses and emotions in people, which is art.”

“[In wrestling] there are elements of choreography and dance and theater, to draw an audience and use your body...What I’m doing is evoking responses and emotions in people, which is art.”

Game Day

Arriving at the site of the match, a concert venue repurposed for the evening, Campos debates how to introduce himself—most people know him only by his ring name.

“Luis? Who? Oh, Little Johnny!” roars one middle-aged superfan from Hong Kong who flew in for the event.

Gomez, the promoter, runs around in an oversized suit organizing everything: couches, meals, even lighting cues.

An unassuming middle-aged Chinese man with a round face and a thin mohawk paces in sweats, twirling a baseball bat. He’s the Slam, who after training professionally in South Korea built a wrestling ring in his own backyard and seems to have taught almost every Chinese wrestler. (“He’s like the Hulk Hogan of China,” Campos says in a whisper, “he’s like everyone’s wrestling grandpa.”) The Slam replaces the baseball bat with a metal trash can, weighing it contemplatively before smacking it over an invisible opponent’s head.

Most of the Chinese wrestlers are in their early 20s. Some left school to pursue their dreams and almost everyone is supporting themselves with side hustles. There’s Bad Boy, a nightclub promoter; Aegon, a former actor in an escape room; and CN, an accountant who came straight from the office to referee. Wade, a young guy from Shandong province in charge of the league’s social media marketing, transforms into the silver-masked Lucha Libre–style character “Platas Mascaras,” billed as hailing from Mexico City. Everyone’s friendly with each other, trading wins, losses, and tips. Campos says he made most of his friends in China from wrestling.

“I really enjoy the duality of being in a space where you can be aggressive, be competitive, but also show care,” Campos notes. “Having a great relationship with your opponent is interesting to me.”

For younger wrestlers seeking to gain a footing, Campos was often their first or second match— his technical experience made him someone newbies could trust to keep them safe. One time he made up a rookie’s face before they went up against each other in the ring.

“It was such a tender moment—I was just inches away painting this guy’s face, getting the details right. And then, ten minutes later, I was beating him up. It’s sort of like mentorship,” he says. “Afterward he hugged me, and said thank you so much for making my dream come true.”

In the locker room, the wrestlers change into their gear, a dazzle of sequins and sparkles, tight leather and flamboyance. A Chinese man with shoulder length blond hair strips down to an orange Speedo then does tricep dips. The Slam holds a cigarette between his lips in front of a no-smoking sign. Campos discusses his plans for a second master’s degree.

The Kyote’s manager, meanwhile, is talking him out of wearing his mask.

“Other guys need gimmicks but you don’t, you’re legit. Look at your ears,” the manager cooes. “Come on, just take the mask off.”

When the maskless Kyote takes to the ring soon after, the crowd’s already rooting for him. Little Johnny, setting the tone, had stolen a spectator’s hat and thrown it away, shoved the ref, and threatened the MC. He begins beating up the Kyote in a manner akin to an older brother subduing a rambunctious younger sibling, but the dominance is a ploy; the match always belonged to his opponent. A series of acrobatic leg locks and a painful, quite realistic chokehold brings Little Johnny to the ground, crawling toward the edge of the ring with the MMA fighter strangling him from the back. The big man, grunting and heaving, finally taps out.

Little Johnny has sacrificed himself to give the league a new hero and the Kyote revels in the glory, clasping the coveted Jade Warrior Championship title belt with a broad smile. Little Johnny storms off stage, a sore loser, in character till the end.

Later Campos rejoins the crowd to watch with his wife, rubbing his neck. After the spectators leave, the Middle Kingdom wrestlers—covered in bruises and welts—clink beer bottles as they disassemble the ring as there’s no crew to do it for them. Unlike the pre-ordained matches, no one knows quite how the future of the league will unfold. Tonight, however, was a success. Campos may have lost, yet he opened a door for someone else to seize the spotlight.

In the months to come Campos and his wife would move to Germany, where Nini is pursuing a master’s in physics and Campos is embracing German as his latest language and aiming to become a university professor of international relations. He doesn’t know if he’ll continue wrestling, but he’s already keeping an eye on the country’s league.

Jack Brook ’19 is a freelance journalist in Phnom Penh. His writing has been published in the Guardian, Al Jazeera, Vice, Nikkei and other outlets.