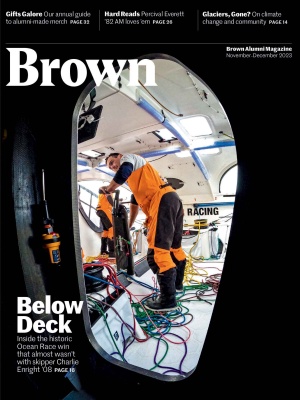

Ocean’s 11

Charlie Enright ’08 and Mark Towill ’11 of the 11th Hour Racing Team on winning the Ocean Race while trying to save the seas.

After winning three straight legs of the Ocean Race, the 50-year-old competition reputed to be one of the longest, most grueling sporting events in the world, skipper Charlie Enright ’08 and his sailing team were on top of the standings. As the only U.S. entry, 11th Hour Racing had a chance for a historic American victory. Then, just 17 minutes after leaving The Hague in the Netherlands on the final leg of the race, Enright was standing on the deck of the Mālama, the team’s 60-foot foil-assisted racing yacht, and spotted something unexpected looming to his starboard side: Team Europe was slaloming straight towards them. Enright barely had time to shout “Starboard! Starboard!” before the bowsprit of GUYOT environnement t-boned the Mālama’s hull at full speed, spearing the cockpit and missing him by mere inches.

You can see the footage of the crash online, not just the helicopter’s view but also the crew’s real-time reaction, thanks to on-board reporters who record and instantly send via satellite footage of everything from a pod of orcas lurking in the Strait of Gibraltar to waves the size of 14-story buildings in the Southern Ocean to gyres of plastic and abandoned fishing nets larger than the state of Texas.

The collision happened six months after the Mālama departed Alicante, Spain, on the 32,000-nautical-mile sailing race that circumnavigates the globe. At that moment, Enright didn’t even know if his boat was still seaworthy, but as British author Simon Sinek has written, “Leadership is not about being in charge. Leadership is about taking care of those in your charge.”

Before examining the Mālama or even inspecting his own body, bruised and jostled by the sudden collision, the TV feed shows Enright immediately peering under the deck to yell, “Is everyone okay? Are we okay?” Thankfully no one on either boat was injured.

The Mālama was towed back to The Hague, where the team found that it had sustained damages serious enough they would be forced to retire from the leg, jeopardizing their entire race. Even at that lowest moment, Enright was composed, thoughtful, neither seething at the other team (the skipper had already apologized and taken responsibility for the crash) nor ready to give up. “This race has a way of testing people in different ways, physically and mentally, and this is a test for our team,” he said at the time. “There is no team I would rather be on, that I would rather have with me. If anyone can figure this out, it is us. I genuinely believe that.”

Though it verges on cliché to call any ship captain even-keeled, Enright embodies a certain unflappable resilience. Competing in his third around-the-world race, he had suffered serious setbacks before—most notably in 2018, when his racing yacht was dismasted off the Falkland Islands after earlier colliding with a Chinese fishing vessel in Hong Kong, killing one of the fishermen. While Enright was not on board at the time of the fatal accident, he still shouldered the responsibility for the whole team.

The bowsprit of GUYOT environnement t-boned the Mālama’s hull at full speed, spearing the cockpit and missing Enright by mere inches.

A champion’s roots

The skipper traces some of that unflappability back to his grandfather, a boat-builder who also went to Brown as a Naval ROTC student, riding to the campus from Pawtucket on a bicycle. And he attributes some of his leadership skills to his Brown sailing coach, John Mollicone, who has directed coed and women’s sailing since 1999. Under Mollicone’s guidance, Enright became a four-time honorable mention All-American.

Mollicone, humbly, modifies that assessment, sharing that Enright arrived at college already something of a sailing prodigy. “Charlie grew up sailing in Bristol,” Mollicone says. “His dad raced, and he won a high school national championship with Milton Academy, so it’s in his blood. He was already a natural when he got here. His personality is perfect for the sport; he’s easy to deal with, steady, dedicated, a great teammate, a hard worker, competitive. When you combine that with innate talent, you have the potential to lead a team to win a race around the world.”

Most collegiate sailing teams are run mainly by volunteers. Brown, with a professional coach, is an exception and the investment has paid off, as one of the University’s few national titles in the last 20 years—in any sport—was won in the Women’s Dinghy National Championship in 2019. Mollicone credits Enright for helping build the program that resulted in that win.

“Charlie was one of my first high-level recruits,” Mollicone says. “He finished top five in multiple national championships. Four-time honorable mention All-American and a huge team leader.” When Enright entered, sailing, though nationally competitive, was only a club sport; now Brown is one of the only universities in the world where sailing is both a club and a varsity sport, engendering an egalitarian spirit contrary to the sport’s elitist reputation. “We offer the opportunity to everyone at Brown,” Mollicone says—including students who have never set foot on a sailboat before.

At Brown, Enright mainly raced collegiate FJs and 420s, double handed dinghies with rudimentary sail controls, the kind you might find at a tonier YMCA. No trapeze. No spinnaker. Just a standard over-the-transom style rudder head and tiller, making the aluminum boat light and durable enough to sail in a variety of conditions. College regattas are held over a weekend and composed of short races that last 18 to 22 minutes.

Keeping the boats simple is meant to make college sailing more accessible, affordable, and standardized. It also meant that the conditions and the boats Enright was racing on in college were vastly different than what he would compete with in the Ocean Race. It would take an unusual year away from Brown to convince him that he wanted to become a professional offshore racer.

At Brown, Enright mainly raced Collegiate FJs and 420s, double handed dinghies with rudimentary sail controls, the kind you might find at a tonier YMCA.

Reality-show racing

Roy E. Disney, an avid sailor and former vice chairman of Walt Disney Co., was recruiting for a reality show, and friends were pushing Enright to take time away from studies at Brown and apply. The idea: a youth crew would compete alongside 73 other starters (the boats compete by class) in the 2007 Transpacific Yacht Race from L.A. to Hawaii for a documentary film, Morning Light. Disney had donated a Transpac 52, a sleek carbon fiber monohull 50-feet yacht. -:

Enright applied begrudgingly. Next thing he knew, he was one of 30 sailors selected, out of thousands, to compete in trials in Long Beach. He made it to the group of 15 who would train for six months in Hawaii before the race, then became one of the 11 final crew members. The film documents the entire process from the initial trials to the finish, and watching the ease with which a young, stubbled Enright, in his ubiquitous baseball cap and sunglasses, rigs a sail makes it clear that he was born to be on the water. His decision to take a year away from Brown to work on Morning Light would change the course of Enright’s life.

First, the opportunity itself was unprecedented. Instead of a 20-minute race on a collegiate sailboat, he would be embarking upon an 11-day trip on a million-dollar racing yacht trailed by the Cheyenne, a 125-foot power catamaran carrying a production team with cameras rolling 24/7. Disney was providing not just the boat, but also some of the sport’s greatest coaches such as former Olympic gold medalist and seven-time world champion Robbie Haines and legendary navigator and multiple world speed record-holder Stan Honey to train the young sailors before they would compete. Many of the coaches on the documentary shoot were Ocean Race veterans. The access was incredible for young Enright. “It was like learning how to putt from Tiger Woods,” he says.

Enright would be racing offshore for the very first time and his efforts would potentially be seen by millions. One way or another, that couldn’t help but alter his future.

Secondly, and more significantly, Enright would meet his future racing partner and cofounder of the 11th Hour Racing Team, Mark Towill ’11, then a senior in high school. On Morning Light, Enright was the oldest cast member, a college senior earnestly growing his mustache and playfully signing off his mid-sea emails as “from the nerve center,” while the handsome, more serious, and less hirsute Hawaiian Towill was the youngest. Despite their differences they connected in their shared level of passion for the sport.

“Mark and I both considered [Morning Light] to be the beginning of our dream, which is the Ocean Race,” says Enright.

Exploration and entrepreneurship

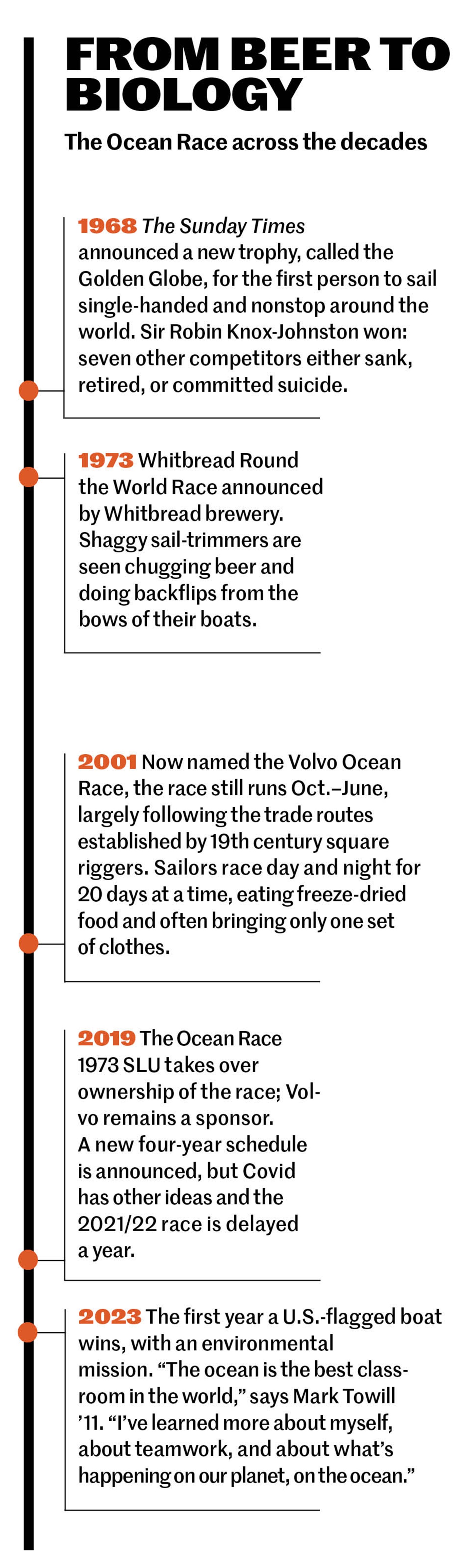

Golf is perhaps a good analogy for sailing, because both carry connotations of exclusivity, sports that hint at a certain social class as much as the mastery of specific physical skills. But sailing has always had the romantic combination of exploration and danger—even the roughest sand trap has no rogue waves or sharks. With the Ocean Race, there’s an echo of Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan’s 1519 circumnavigation of the globe, which historian Laurence Bergreen calls “the greatest sea voyage ever undertaken, and the most significant,” though it’s worth remembering that he was a barbarous slaver who had the mutinous men on his ship beheaded and tried to force his beliefs on Indigenous populations; the darker implications of the trip that ended in his death fed generations of colonialism to follow. Still, the allure of traveling into the great unknown, despite unforeseeable peril, persists in the human imagination. This fascination, in part, gave birth to the sport in which Enright is now “top dog in the world,” according to Mollicone (see timeline).

When Enright and Towill got started pursuing their dream, they were the new kids on the block. But instead of joining a team at an entry level, they decided they were going to assemble their own team, overseeing every aspect of it. “We took on fundraising, finding sponsorship, building the team,” says Towill. He attributes this entrepreneurial spirit to the Open Curriculum. “If you’re interested in something, just study it. Explore and chase your dreams and dream big,” he says. “I tie that mentality back to Brown, which is a shared experience that both of us have that I think is a big part of our success.”

During their first two Ocean Races, Enright and Towill sailed together, but for this latest victorious campaign, Towill concentrated on the commercial side while Enright skippered. One would imagine this would be a disappointment, but for Towill it just made sense. “Charlie is a great skipper,” Towill says. “He’s incredibly focused and determined. Obviously, he’s very talented. What makes him stand out is how much he cares about people. That helps him understand the nuances of how to run a team and when to be forceful if you need to be. But I think more importantly, it makes him empathetic and helps him get the best out of people. I think he understands that to be successful, you need to surround yourself with people who are better than you.”

Because each race changes class, in 2017 the Ocean Race allowed for nine members on the boat, whereas the most recent edition allowed for just four sailors and an on-board reporter. Conversely, the 11th Hour team grew from 15 to 35 people in proportion to the scale and complexity of their operation, so for Towill, “it felt like the right time to step back from sailing to help run the team.” Plus, their boat Mālama, which was specifically designed for the sailing team with input from Enright and naval architect Guillaume Verdier, required constant attention to complete, especially given 11th Hour Racing’s larger ecological imperatives.

Sailing towards sustainability

Sailing has transcended mere sport for Enright and Towill; it has now become a platform to discuss ocean conservation and environmental sustainability. “The first lap of the planet was an awakening in terms of marine debris,” Enright remembers. “You can’t even count the number of useless plastic water bottles that we see. Everything you see on land ends up in the ocean.” He was sickened by what he saw amid the coral and sea turtles and knew that he had to do something beyond simply bear witness. “We are canaries in the coal mine,” Enright says, “because no one can speak to ocean health with as much credibility as we can. But I’m sick of talking about how dire this situation is. Let’s fix this.”

Enter their partnership with 11th Hour Racing, an environmental group based in Newport, R.I., that is focused on marine health. The name, they explain, “comes from our sense of urgency: we are at the final hour in the struggle to save our ocean.” The mission ties in perfectly for Towill, who came to Brown because growing up in Hawaii, he wondered why his state was so “dependent on oil and gas for energy, even though we have sun and wind and solar and geothermal and hydro.” Rob MacMillan, the cofounder of 11th Hour Racing, characterizes their work as both global and regional, and he sees sport as a way to galvanize people into action. “Here in Newport there’s a push to do large-scale composting, because by 2030, landfills are going to be full and much of that waste is food waste. And soil health has an enormous indirect impact on ocean health. So in order to generate greater awareness, we use sailing and spokespeople like Mark and Charlie because they are frankly much more interesting than I would be.”

Enright calls for better regulation for the marine industry—and the partners build their own boats from alternative materials. “Instead of carbon fiber, we are using alternative materials such as recycled carbon, fiber, flax, bio resin, and bamboo,” he explains. “If we don’t do this experimentation, it will never become commonplace down the road.”

“We are canaries in the coal mine, because no one can speak to ocean health with as much credibility as we can. But I’m sick of talking about how dire the situation is. Let’s fix this.”

Additionally, 11th Hour Racing has helped mandate that every competitor in the race carry a water sampling system so that “we can collect data in parts of the world that nobody else goes to, and that data gets sent back to climatologists and meteorologists to help enhance the accuracy of their models.” While out racing their yachts, they are also “testing for sea surface temperature, salinity, even eDNA, which is a relatively new concept,” says Towill. “It’s been quite rewarding to be able to contribute to the general scientific database in our own way,” he continues, though the results have been sobering. “What we found through our microplastic testing is that even in Point Nemo, what arguably is the most remote corner of the ocean on the planet, a place where the nearest humans are on the international space station, there was evidence of microplastics.”

The environmental mission is why the 11th Hour Racing team named their boat Mālama, which means “to care for or protect” in Hawaiian, and it particularly resonates for Enright now that he has two young children. “Every aspect of our campaign is looked at through a sustainability lens now,” he says.

Being on the ocean has greater spiritual significance in his life these days. “You get a heightened sense of awareness, an appreciation, and a newfound respect for the elements,” Enright says as he describes rounding Cape Horn, a journey that fewer sailors have completed than climbers have scaled Mount Everest. “Seeing the sky undisturbed by the noise of lights, sailing through Southeast Asia, seeing atolls that few people have ever laid eyes on, crossing the equator...there are times when you feel like the luckiest person in the world.”

“It’s a double-edged sword,” he admits, “because my kids are 6 and 7 and they’ve seen more of the world than most average Americans, but I’m also away from them for months at a time. I’m in awe of my wife because she’s been raising those kids on her own for the better part of six months, so it’s an intense sacrifice.”

Then there’s the reality—olfactory and otherwise—of being scrunched in a 60-foot carbon hull with five other people for days on end, with no toilet, no running water, no palatable food. The constant challenge and fatigue give those few moments of sublimity a burnish like no other and make someone like Enright want to come back home to hold his family tightly and then tell the world about what he learned on his latest journey.

“This last Ocean Race, one of my most profound moments was realizing the implications of sharing the ocean with all this miraculous marine life—dolphins, sharks, whales, turtles, orca, flying fish,” says Enright. “We share the ocean. We are far from its only inhabitants. As humans, we make thousands of decisions a day, conscious or subconscious, and they all have consequences. So the more we can bring consciousness to that process the better.” Accordingly, one of 11th Hour Racing’s objectives is to give young people access to the sport of sailing. “The more people who get to experience that, the more invested they would be in helping preserve this precious resource,” says MacMillan.

In a sense, the goal of victory in a yacht race, with its connotations of luxury and privilege, remains secondary to the work 11th Hour Racing is doing to help raise ocean awareness. However, winning the Ocean Race certainly couldn’t hurt in elevating the profile of their mission. And sure enough, on June 29, 2023, after an agonizing wait and a courtroom-style hearing, 11th Hour Racing was handed the victory. Not, of course, by sailing to the finish line first—the crash had killed that dream. But the World Sailing International Jury awarded the 11th Hour Racing team points of redress that, added to the points the team had earned across all legs, made them the very first U.S.-flagged boat to win the Ocean Race. Redress, as defined by the Royal Yachting Association, is compensation given when “a boat’s score or place in a race or series has been, or may be, through no fault of her own, made significantly worse.”

Enright and his crew heard the news via satellite phone call just hours before arriving at the final port in Genoa, Italy, for the traditional champagne-suffused trophy celebration. If it was bittersweet to win the prize in such a fashion, it didn’t show on the skipper’s ebullient face.

“I’m absolutely ecstatic,” Enright said in Genoa. “There have been highs, some incredible highs, but also lows that have knocked us all, but they were all worth it to hear this news today.” The little boy whose grandfather had babysat him by sending him out on his own to sail around Bristol, Rhode Island, had now captained the team that had just won one of the world’s most arduous and prestigious sailing competitions.

What comes next for Enright after the fulfillment of this lifelong dream? He remains unsure, enthusiastically so. For now he is satisfied to be back on land, with the ones he loves, his name forever etched in the annals of sailing.

Ravi Shankar is a creative writing professor, translator, and Pushcart Prize–winning poet. His memoir Correctional was published in 2021.