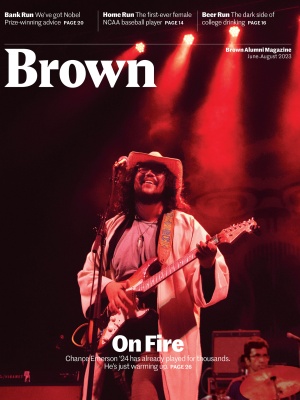

Chance Emerson & the Series of Improbable Events

A band cobbled together before classes started freshman year has performed onstage in front of 3,000 people, opening for Blues Traveler. What’s next for Chance Emerson ’24 and his bandmates? First, homework.

Chance Emerson ’24 arrived on campus in August 2019 with a couple of suitcases and a to-do list.

A singer-songwriter and guitarist since his early teens, he’d already released his first EP as a junior in high school. But his boarding school was light on musicians to collaborate with—there were only a handful of bassists and drummers, and none of them were playing indie folk. “As soon as I got to Brown, my goal was to start a band,” Emerson recalls. “I’d been itching for it for so long.”

He already had a lead on a second guitarist—he’d heard about Will Beakley ’23 from Beakley’s cousin, whom he’d met while hiking in New Zealand during his gap year. It didn’t take long to convince Beakley that they should start a band. Guitarist? Check. A day or two after move-in, hanging out in his dorm room on the second floor of MoChamp, he heard piano music coming from down the hall. He stuck his head into the room and saw Satch Sumner-Waldman ’23. Keyboard player? Check. At a party the next night, he ran into a guy wearing an unbuttoned Hawaiian shirt and a bass clef necklace who introduced himself as Jacob Vietorisz ’23. The question asked itself. Bassist? Check.

“At this point, all we need is a drummer,” he says. “But I am having a tough time finding the drummer, like a really tough time.”

He asked around; several people mentioned Jack Riley ’23, a drummer from Los Angeles. So Emerson tried to get in touch, first by email, then by text. Radio silence. All he knew was that Riley lived somewhere in Andrews Hall. So Emerson and Beakley decided it was time for some good old-fashioned detective work. They started on the top floor and worked their way down, checking the names written on each door. On the second floor, they finally spotted a Jack. They knocked and asked if Jack Riley lived there. No dice.

“As soon as I got to Brown, my goal was to start a band,” Emerson recalls. “I’d been itching for it for so long.”

So they kept going, all the way down to the basement. They were running out of rooms. Then they saw it—another sign for another Jack. They knocked on the door, and there’s a guy lying in bed. They ask if he’s Jack Riley. He says yes. They ask if he wants to join their band. Sure, he says. Drummer? Check.

Orientation isn’t even over yet, and Emerson has a band. Check.

“You should know ‘Imagine,’ bro.”

A little more than three years later, on a rainy October night in Montclair, New Jersey, Emerson and his band are lounging in one of the Wellmont Theater’s green rooms, eating mediocre Cuban sandwiches and getting ready to open for Blues Traveler, the Grammy-winning band of “Run-Around” fame.

“Yo, Chance,” comes a voice from outside the open door, and Tad Kinchla ’95—the bassist for Blues Traveler—leans his head in. “Yo, hey, do you know, like, ‘No Woman No Cry’ or ‘Imagine’ or…” he trails off, trying to think of a third option.

Emerson hesitates. “You should know ‘Imagine,’ bro,” Beakley chides.

“Do you know it?” Kinchla asks again. “Would you want to sit in with us? Just alternate verses, do a verse and then maybe share on the third and then do the choruses. You down?”

“Yeah, that’d be sick,” Emerson says, enthusiastically.

Kinchla heads back downstairs, and Emerson plops down on the couch. “So, I’m just gonna start listening to that over and over again,” he says, pulling up Spotify on his phone and setting it on the arm of the couch. “I know how the tune goes. I don’t know any of the words, though.”

It’s not uncommon to find Emerson and his band—all STEM concentrators, three-fifths computer science—studying furiously before or after shows. Being simultaneously enrolled at Brown and on tour will do that to a person. Playing in the band and managing college courses is a delicate balancing act, and this tour is a case in point. Emerson and his band were originally offered 14 dates by Blues Traveler’s manager, but they took only seven—the ones clustered around a long weekend in October—in order to miss as few classes as possible.

For tonight, though, the assignment isn’t school-related. It’s 7 p.m. and they go on at 8:10. Time for Emerson to cram.

“What is the goal now?”

The band had their very first jam session in the basement of Andrews, Riley drumming on an upturned recycling bin, Emerson strumming an acoustic guitar, Sumner-Waldman playing a miniature keyboard. But forming a band was only the first line item on a very long to-do list. Next up: Play a show. They took care of that one in short order, performing at an off-campus house on Waterman Street, then downtown at a 300-person venue known as Dream Haus.

So Emerson started to think bigger. “What’s the best venue?” he wondered. “Or, what’s the best venue that feels even remotely attainable?” He decided it was the Met in Pawtucket. They were delayed by the pandemic, but they managed to book a show at the Met by September 2021—and it sold out. “And I was like, ‘Oh my God. I don’t know what to do now. That was the goal. What is the goal now?’”

Collectively, the band’s favorite band is Lawrence, a soul-pop group that also formed at Brown (seven-eighths of the members attended Brown). Since leaving campus, Lawrence has performed on Jimmy Kimmel Live, The Today Show and, in 2019, were signed by Grammy-winning producer and musician Jon Bellion. Could Emerson’s band, possibly, open for Lawrence? In March 2022, at Fête Ballroom in Providence, they did just that.

A month or so later, they managed to headline their own show at Fête. Then, during finals, Emerson was invited down to Nashville by a management group to play two shows. “It was just the craziest feeling,” he says. “It’s like this series of improbable events.”

It’s not uncommon to find the band studying furiously before or after shows. Being simultaneously enrolled at Brown and on tour will do that.

“He’s a go-getter,” says Riley, who shifted from drummer to bassist for the band in 2021 when Vietorisz left to focus on his studies. “If he wants to make something, he’ll do it. If he wants to meet someone, he’ll try to meet them. He’s got this incredibly long to-do list that I see every day. And he just does it.”

“All these things that we see people do on social media, like musicians we idolize, like, those are things that we can do at some point in the future if we work for it. It’s super energizing to be with a friend who’s like that.”

“The most personal parts of me.”

Next on Emerson’s list? Releasing and promoting his most recent album, Ginkgo, which dropped May 5th. “This is my most official, honest, best work I’ve ever made,” he says. “It was written in car rides back from shows and the middle of nowhere in New England. It was shedded in practice rooms, it was written in Hong Kong and Taiwan, it was written during COVID, it was written in Perkins, it was written here,” in his off-campus house on Barnes Street.

Ginkgo is not Emerson’s first album. But it is the first one he allowed someone else to produce. Before that, he wrote, arranged, played, and produced everything on his own. “My music was mine,” he explains. “I was scared to share. I refused to let anyone else touch it, because these are the most personal parts of me.”

“He’s a perfectionist,” acknowledges Riley. “He wants stuff to be right, and I’m all for that. I basically sat down—with maybe a little more confidence than I should have had at that time—and was like, ‘Hey, man, your stuff sounds great. Just give me a track. I’ll make it sound better.’”

This was in 2020, in the midst of the pandemic. Emerson had relocated to his parents’ place in Hong Kong, taking the year off from Brown and enrolling in a master’s program in archeology at a local university instead. Riley was living at home in Los Angeles and taking Brown courses remotely, including one with Jim Moses.

At first, Emerson allowed the files to exist only on his computer. The pair would video chat, Riley suggesting changes and Emerson making them himself on his own mix file. But soon, they were sending the file back and forth.

The time difference meant that Emerson would routinely wake up at 7 a.m. to catch Riley in the late afternoon. “He sent me acoustic demos, and I recorded drums in my garage and bass and stuff on my own in my house. So there was a back and forth,” Riley explains. “I’ll try to put a little bit of my spin on it, and then he pushes back a bit, and then we find some interesting sound that’s kind of a middle ground.” This newfound collaboration led to an EP, On the Monotony of Being, which came out in October 2021. But it wasn’t until February 2022 that the pair “cracked the code” for the sound on the new record, Emerson says.

“We want the drums and the bass to feel like a pop song, a whole electronic vibe,” he explains. “And then we want the top end to be messy and bold and folky and fun. It keeps some of that spontaneity from live music.”

It also reflects Emerson and Riley’s evolution as musicians and songwriters. “I sang like a choirboy for a long time, like very clear, no gravel,” Emerson says. “I found the rasp and soul in my voice in college, playing basement shows, and realized that was something I had that was unique, that other people didn’t.”

This past spring, the pair were back on campus and they spent most of their time in Steinert, recording. “I remember there was one weekend we booked like 20 hours in the studio, and we used all of it,” Emerson says. “We used every single hour and probably more over spring break.” They were racing against the clock—or, more specifically, May, when Emerson’s allergies hit.

“If he wants to make something, he’ll do it. If he wants to meet someone, he’ll try to meet them. He’s got this incredibly long to-do list that I see every day. And he just does it.”

“I think both [Emerson] and I are looking at ways to combine the accessibility of pop with some kind of statement that you can’t get anywhere else, some kind of sound you can’t get anywhere else.”

“You can’t just say lines.”

It’s 7:45 p.m. in the green room at Wellmont Theater and it’s starting to get down to the wire.

“Ready?” Emerson asks drummer Sannivas Reddy Nallamanikalva ’24. He launches into the opening lyrics of “Imagine.”

“No, you can’t just say lines,” Reddy Nallamanikalva stops him short. “I’m gonna check the lyrics.” He pulls them up on his phone. “Okay, start.”

“Imagine there’s no heaven. It’s easy if you try…” Emerson begins again. As he continues on through the first and second verses, Reddy Nallamanikalva corrects any missteps.

“I hope someday you’ll join us and the world will live as one,” Emerson concludes the second verse.

“Be as one,” Reddy Nallamanikalva says.

“Semantics,” he retorts, earning a laugh from his bandmates.

On the other side of the green room, Sumner-

Waldman is busy workshopping a LinkedIn connection request message with Riley and Beakley. Emerson, who took a year off during COVID, will graduate a year later than the rest of the band. Three of the band members are facing a looming deadline—what they’ll be doing in a year. Not to mention worrying about finishing midterms.

“There’s something just so surreal about me and my housemates slash bandmates starting out in the basement of Andrews and ending up on stages in front of like, you know, 3,000 people, and then going backstage, finishing our computer science homework, and then sprinting back out to sign 50 to 100 T-shirts that we sell,” Emerson reflects.

There may have been a dearth of musicians to collaborate with in high school, but since he’s arrived at Brown, Emerson has made connections at a pace that indicates he’s making up for lost time. “I really do not think I would be doing this if I were not here and if I had not met the people I did. Everyone is super into something. It doesn’t matter what it is—you have friends who are world-class athletes, you have friends who are incredible, published poets. And then those people have time to watch me sing because they want to support me, and I want to support them. It’s just this crazy little ecosystem.”

The ecosystem extends beyond campus, too. Adjunct Lecturer Deborah Mills-Scofield ’82 was the one who connected him with Clyde Lawrence ’15, who cofounded Lawrence with his younger sister, Gracie ’20. Lawrence suggested touring colleges to build up experience and connections, which Emerson and his band did in Fall 2021. Riley spent last summer working at Shortstack, a Brooklyn studio founded by Peter Enriquez ’16. That’s where Emerson and Riley recorded a lot of the vocals for Ginkgo—staying up some nights till midnight or 1 am when the studio was free.

“I hit replay three or four times.”

Emerson also connected with producer/songwriter Nick Sarazen ’17 on Instagram, before meeting him in person at the 2022 Newport Folk Festival. Sarazen himself is a testament to the power of networking. His career got a jumpstart from a friendship with a songwriter that began on Twitter; since relocating to L.A. in 2019, he has produced D Smoke and Snoop Dogg’s lead single ‘Gaspar Yanga’ from the 2020 album Black Habits, which was nominated for a Grammy; cowritten “Marry Me,” the title track from Jennifer Lopez’s latest rom-com; and worked with Saweetie on a track for the soundtrack to the Margot Robbie–led movie Birds of Prey.

Sarazen wanted to help, and when he heard Chance was working on an album, he told him to send the tracks and he’d give feedback. He was blown away, particularly by the track “Angela,” which falls about halfway through the album.

“I sang like a choirboy for a long time, like very clear, no gravel. I found the rasp and soul in my voice playing basement shows and realized that was something I had that was unique.”

“I hit replay on ‘Angela’ like, three or four times, I think,” Sarazen says. “The hook really comes in and it kind of explodes. And you’re like, wow. The production gets huge. [The songs] feel like anthem songs, like big rock-type stadium songs.” From folk to pop to Americana, “I was surprised how many worlds he was fitting into one song.”

Sarazen also had notes—he thought the lyrics for another track, “Game Theory,” leaned a little too heavily on actual game theory as a metaphor for a breakup. “I just really felt that the complicated nature of the lyrics was taking away from the rest of what the hook was doing, melodically and delivery-wise. So I was like, I think you can simplify. Don’t change the message, because the message is great. Just don’t overcomplicate the way that you’re communicating it in the hook, lyrically.” So Emerson went back and took out all the “SAT words.”

“But I thought it was a really cool exercise to do that with such a complicated idea,” Sarazen adds. “A lot of songs, you’re not starting at a complicated idea. If you’re aiming for a pop song, you only have a handful of general concepts that you’re talking about. ‘Game Theory’ is really just talking about heartbreak, but it’s very unique to [Emerson] and very unique for a song.”

“It’s like a first date.”

The oldest song on Ginkgo is “Ecstasy,” which Emerson wrote during that very first jam session in Andrews. “I always write a lot of songs,” he says. “And it’s interesting to me which ones stick around, and why. The lyrics are so honest. It was the first relationship where I felt like I was in love. Like, I was really in love. And I was like, this is crazy. I get it, I get why people would fight wars for this.”

“Ecstasy” is a love song, but Ginkgo is a relationship album—heartbreak and all.

“It’s my take on adolescent or early adulthood relationships. It opens with romance, falling head over heels, madly in love. And then there is a breakup, and the immediate aftermath of like, Oh, my God, I am crushed, I don’t know how to function. And then there is the period of redefining who you are alone. It’s like, I don’t know who I am anymore. How did this happen? Rebuilding your identity as a single person. And then, all of a sudden, you fall in love again, and you do the whole thing again.

“It just felt very cyclical to me. And my idea was like, if you just looped the album, it parallels what happens because it’s like you’re in love, fall out of love, you recover from all that damage, and then you fall in again.”

It’s 8:55 p.m. in Montclair, New Jersey, and Emerson and his band are wrapping up their set, playing the final notes of “Ecstasy.” Onstage, he wears a black embroidered Western shirt over a graphic tee; it’s a visual nod to the amalgam of styles contained in his music. Once the band is through with “Ecstasy,” Emerson tips his cowboy hat to the crowd and starts to introduce the band members over the opening chords to “Angela.”

Backstage after the set, Emerson runs by Blues Traveler’s green room to ask when he should plan to join them onstage to sing “Imagine.” There’s been a mix-up—it turns out Kinchla was talking about tomorrow’s show.

But that’s life on tour—you have to roll with the punches. Tomorrow, the band will deal with a flat tire on their trailer on the way to Virginia; tonight, it’s time to head out to the merch table to sell some T-shirts.

As Emerson navigates through the crowd to get to the merch table in the back, he’s stopped by three different people who shake his hand and congratulate him on a great show. “When you’re up there, it’s almost like you’re introducing yourself,” he says. “At least, that was my position as the opener. It was like, ‘Hello, I exist. This is who I am. Take it or leave it. Hope you like it. Love you. Bye.’ You put it all on the table, and you hope that people like what they see. It’s like a first date.”

And people were ready for that second date—in some cases, literally. Some of those same audience members showed up at a show he organized at Providence’s Avon Cinema a few weeks later.

Could it be the start of something serious? Only time will tell.

Abigail Cain ’15 is a freelance writer and a content strategist at BuzzFeed.