Running from the Bear

Douglas Diamond ’75 compares bank runs to a bear encounter gone bad—flee and you’re f@#%ed. His analysis helped save the U.S. economy in 2008 and won him a Nobel Prize last year.

Early one October morning in 2008, as the financial crisis threatened to spin out of control, Douglas Diamond ’75 arrived at the Federal Reserve for a meeting with Chairman Ben Bernanke. Diamond—considered to be the intellectual “father” of modern banking theory—was among a handful of the nation’s top economists who’d come to offer their perspective to the central bank’s top policymakers. But as 9 a.m. came and went, neither Bernanke nor the other Fed officials showed up. Only after waiting hours in a conference room, drinking coffee, did the economic brain trust discover what was amiss: Bernanke and the Fed’s board of governors were locked in emergency negotiations to keep Wachovia Bank from collapsing. By the time Diamond and the other economists finally got a chance to offer their advice, most of the exhausted Fed officials had left. Only Bernanke remained to hear it.

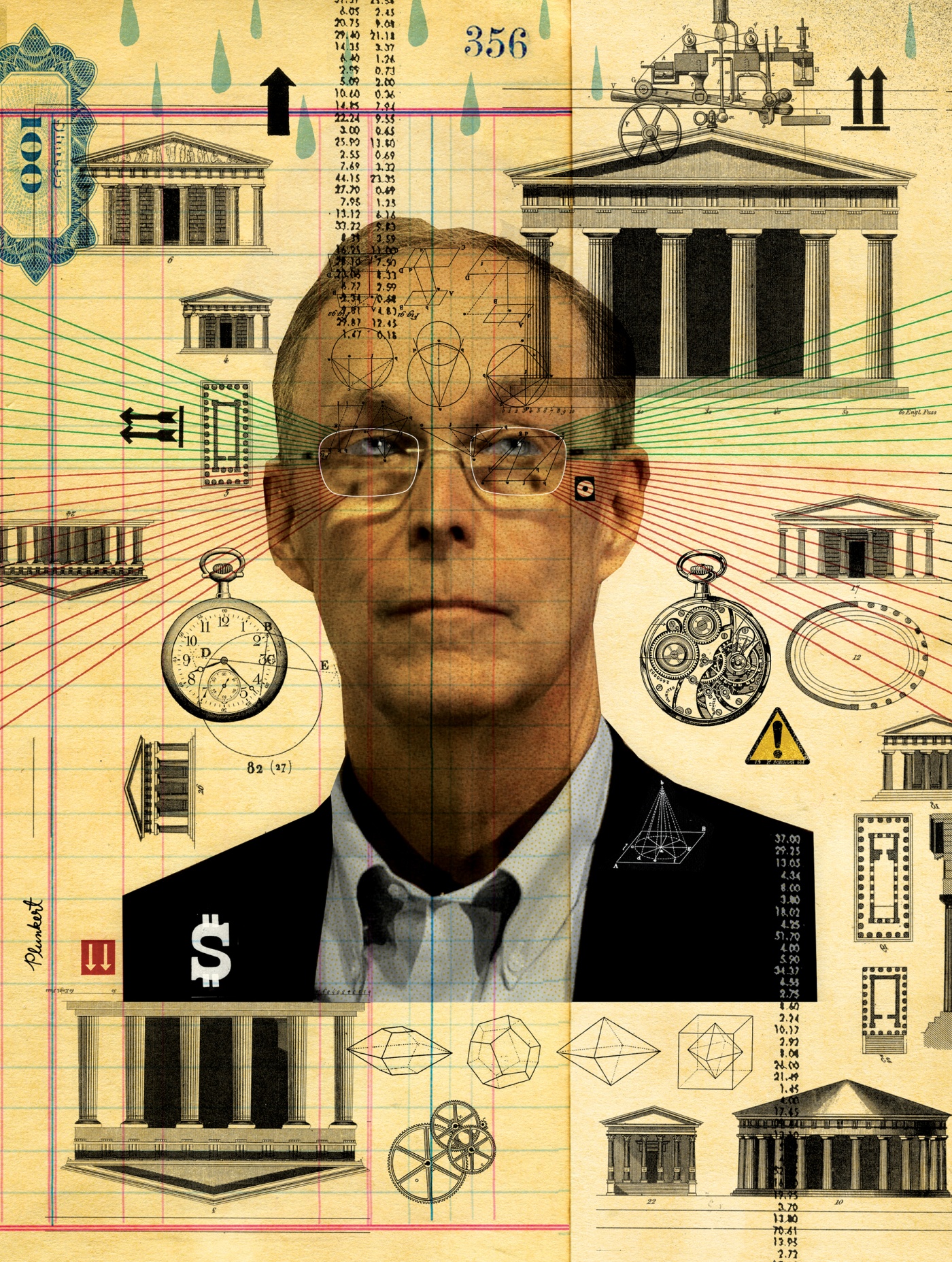

So it’s perhaps not surprising that when Bernanke received the 2022 Nobel Prize in economics in Stockholm last December, one of the fellow laureates who joined him on stage was Diamond, a soft-spoken theoretical economist who helped organize that Washington tête-à-tête. The Nobel committee honored the pair, along with Diamond’s coauthor Philip Dybvig, for groundbreaking work from the early 1980s that shed new light on the role of banks in the economy—why they’re essential, but also why they’re so vulnerable to failure and what can be done to keep them out of trouble. The trio’s Nobel-prize-winning research not only proved critical in helping policymakers understand the root causes of the 2008 crisis; it also laid the foundations for many of the policies the Federal Reserve adopted to keep the world from falling into a second Great Depression.

Diamond may be far less publicly known than his famous colaureate, but within finance he is equally influential. After Brown, he earned a PhD in economics from Yale before joining the faculty of the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business in 1979, where he has taught since. Diamond’s early work centered on two deceptively simple questions: Why do banks exist? And why are they subject to destructive runs that can destabilize the economy? The answers he arrived at changed how economists think about finance, says Raghuram Rajan, a former governor of India’s Central Bank and a longtime Booth School colleague. Those early works created a kind of “aha moment,” says Rajan, a frequent coauthor. “He’s quite good at taking these complex concepts and really bringing them down to the core.”

That’s certainly the case with his seminal 1983 paper, written with Dybvig, which explains why banks are vulnerable to runs and why a government backstop is needed in order to avoid the devastating impact bank failures can have on the real economy. So well-known that economists simply refer to it “Diamond-Dybvig,” the paper remains one of the most widely cited in economics.

“If we both run, the bear will chase us.” And in that situation, he adds, “I don’t have to outrun the bear. I just have to outrun you.”

That may seem strange, since bank runs are nothing new; they occured frequently throughout the 1800s and were a major cause of the Great Depression. And you don’t have to be a finance geek to know how destructive they are; anyone who watched customers race to pull their money from the fictional Bailey Building & Loan in It’s a Wonderful Life knows the panic they cause. But as Diamond was starting out, economists didn’t clearly understand why seemingly strong banks could suddenly collapse. Was it because they held bad assets and weren’t truly solvent? Or were banks structuring their contracts with depositors and borrowers poorly, in a way that research could help fix?

The answer, they found out, lies in the mismatch between the time frames of depositors and of borrowers. Depositors typically put savings into short-term accounts, so they can withdraw needed cash quickly. Banks then pool those deposits to make loans over a much longer period: think a homeowner with a 30-year mortgage, or a business owner who takes out a 10-year loan to buy machinery for her factory.

The economy benefits when banks play that crucial role of transforming short-term deposits into long-term loans—what Diamond calls “the magic of banking.” Savers earn interest on unneeded cash, borrowers get funding, and the economy grows. Banks need only keep enough reserves on hand to meet withdrawals. Say, for example, only 3 percent of depositors need cash on any given day. “You keep that much at the bank in liquid assets, and the remaining 97 percent can be invested in longer-term, more illiquid assets,” says Rajan. “And everybody’s happy.”

But what happens when depositors fear their bank is in trouble? In what’s come to be known as “the economics of panic,” Diamond’s work with Dybvig showed that the timing mismatch, normally the source of the bank’s strength, leaves it vulnerable instead. Once depositors decide to pull their money, a bank can quickly run out of funds, since those long-term loans can’t easily be converted to cash. Depositors’ fears can turn into a self-fulfilling prophecy as everyone rushes to get their money out first.

Diamond likens a run to the old adage about two people who encounter a bear. “If we would both stay still, the bear will go away. But if we both run, the bear will chase us,” he says. And in that situation, he adds, “I don’t have to outrun the bear. I just have to outrun you.”

It’s well accepted now, but their key insight—that the timing mismatch, rather than bad or risky assets, is often what causes runs—was new. “What they did was create a very simple and elegant way to characterize the fragility and show how you can have a banking system that looks perfectly normal and then suddenly collapses,” says Mark Gertler, a professor of economics at New York University. “Even though the bank is solvent, it’s unable to function because the existing depositors panic.”

That analysis also held major implications for policy: it showed that government intervention is the only way to end such panics without damaging the crucial role banks play in supporting economic growth. For traditional commercial banks that means federally-backed deposit insurance, while for investment banks, hedge funds, and others operating in more lightly-regulated “shadow banking” sectors it often means relying on Fed support in its role as a lender-of-last-resort.

Just as important, the pair showed that the risks to the economy from “bank” runs don’t occur just in banks. The very same panics can happen anywhere that mismatch between short-term funding and long-term assets exists. “The point of Diamond-Dybvig was that it’s not about the bank; it’s about the short-term debt,” says Diamond. Or, as he put it in his Nobel acceptance speech at the Stockholm Concert Hall last December, “Private financial crises are everywhere and always about short-term debt.”

That insight proved prescient in 2008, following Lehman Brothers’ collapse. Markets seized up amidst the self-fulfilling panics that Diamond had predicted, as everyone wondered which financial institution they dealt with might fail next. And any economist who had studied Diamond-Dybvig quickly saw the implications. “You couldn’t look at some of these episodes without thinking, ‘Holy cow, maybe this is Diamond-Dybvig,’” says Robert King ’73, ’76 AM, ’90 PhD, a professor of economics at Boston University, who first met Diamond while earning his PhD at Brown. Their work “framed a lot of how people interpreted the events.”

Economist Paul Krugman, himself a Nobel winner, put it more bluntly: “In the days after the fall of Lehman, economists could in effect be found roaming the halls of their departments, muttering ‘Diamond-Dybvig, Diamond-Dybvig,’” he wrote after the prize was announced.

And that’s how a 25-year-old paper came to provide much of the theoretical framework used to understand what was happening in the financial crisis and guide the policy response crafted to end the panic. Like them or not, Diamond’s work—together with Bernanke’s research—helped provide much of the rationale for the enormous bailouts that the Fed engineered for the financial sector, providing hundreds of billions for loans and to buy up troubled assets, as well as policies that forced investment banks and others to significantly increase capital reserves.

The irony is, Diamond never intended to become an economist. He took a few economics courses in high school, which he found too easy. He came to Brown planning to become a molecular biologist but hated freshman organic chemistry and dropped it two weeks into the semester. Needing a replacement class in the same time slot, he opted for advanced microeconomics. After a few more courses and a summer stint working on a medical malpractice reform bill in Rhode Island that got him jazzed about the policy side of economics, he decided the subject wasn’t “as trivial as it had seemed.”

The years of easy liquidity have left many acting like homeowners who install a one-inch sump pump in the basement rather than one that can handle a bigger downpour.

It was a senior year course in monetary policy taught by the renowned economist Jerome Stein that turned him toward a finance career. Stein’s course focused on the banking crises of the 1930s and earlier. Fascinated by what he learned about both the successes and the failures of policymakers in combating such crises, Diamond had an insight that fueled his Nobel-prize winning work and much of his research since. “I realized that how monetary policy worked, and how it affected banks and the financial system, was still very up in the air,” he says. “It was not well understood.”

Even back then, friends and colleagues say Diamond stood out. They describe him as equal parts humble and brilliant. While still a senior, he took an advanced money and banking class designed for second year PhD students. Boston University’s King, then working on his doctorate, was in that class. “There are very few people who have the kind of evident intellectual depth that Doug did at that time,” says King. “Doug’s kind of a quiet guy, but when he would say things, it was worth listening. If you’re not listening carefully, you’re going to miss something really valuable.”

That’s a view shared by many of the graduate students Diamond has advised over the years; despite his renown within the profession, they say he remains a remarkably generous and supportive mentor. “What makes Doug special is how giving he is to his students,” says Maryam Farboodi, an assistant professor at MIT’s Sloan School of Management. During many long conversations while she worked on her 2014 doctorate, she admits she often didn’t quite understand the point Diamond was making. “I would think, ‘Oh, what he’s saying is not that related.’” Only weeks later, while continuing her research, would she realize “Oh, my gosh, this is what Doug mentioned a month ago!” She adds that Diamond likely knows that others often don’t grasp his ideas on the spot. “He’ll still share them, with the hope that maybe students later get it,” she says. “His insights are really above and beyond.”

What does Diamond see on the horizon now? He says many banks are in far better shape today, and regulators much more prepared to tackle a crisis. But as the recent turmoil in the sector has shown, that hardly means no cause for worry. After years of near-zero interest rates many firms hold too much debt. “There’s been too much liquidity, lots and lots of liquidity sloshing around,” he says. With the Fed raising rates to combat the resulting inflation faster than expected, he warns, that could mean trouble. “We’re in uncharted territory.”

As the value of that debt falls, or becomes more expensive to service, the risk of bankruptcies will rise. The rapid fall of Silicon Valley Bank following a massive bank run in March, and the collapse of Credit Suisse and First Republic since, shows that not all have learned the lessons of the past. And even as the Fed moved swiftly to calm fears that their troubles could set off another system-wide banking crisis, Diamond points out that the vulnerabilities that could lead to another crisis could also occur elsewhere: in insurance, in mutual funds, or within corporate firms themselves. One area of particular concern: “leveraged loans,” a form of corporate debt that typically goes to companies that already have lots of debt or a poor credit history. As long as Fed hikes continue and the risk of recession remains, Diamond warns that problems could snowball again through the shadow banking sector as those companies struggle to repay.

Ever the professor, Diamond turns again to a simple metaphor to make sure his point is clear. The years of easy liquidity have left many acting like homeowners who assume a long stretch of minimal flooding will continue, so they install a one-inch sump pump in the basement rather than one that can handle a bigger downpour. “If we get three inches, or a foot, bad things are going to happen,” he says.

And what of crypto, where leading exchange FTX suffered a classic bank run last November? Valued at $32 billion, FTX collapsed in just five days as fraud allegations sent depositors and investors racing for their cash. It’s hard to look at that decline—and the cascading failures it caused—without again instantly thinking “Diamond-Dybvig” and wondering what the implications of Diamond’s work are for the nascent, largely unregulated sector. Might deposit insurance be needed? Is there a point at which the Fed provides support, as elsewhere, to restore stability and ensure that the loss of confidence in crypto doesn’t spread elsewhere in finance?

Not if Diamond has anything to say about it. He dismisses cryptocurrencies as little more than an unsafe speculative bubble, akin to trading with a bookie with a bad reputation. “These things are designed to look safe and honest, but because they’re opaque and hard to see, they’re just fraud for the masses,” he says.

Diamond recalls seeing the now infamous commercial featuring comedian Larry David touting FTX during the 2022 Super Bowl. That ad scared him, he says, and he regrets not saying anything publicly at the time. But better late than never. So, if you’d like a little investment advice from a Nobel laureate, consider this: “If you don’t understand something, stay away from it,” he says. “You should just assume that anything you see that isn’t completely audited and regulated, it’s not for you.”

Jane Sasseen is the executive director of the McGraw Center for Business Journalism at CUNY’s Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism.