One Grange Hall, Two Alums,

and 9,000 Books

The birth of a place for books and community,

in rural Maine.

in rural Maine.

Ann Weiss (then Charlton) graduated from Pembroke in 1965, a year after Brown dedicated the John D. Rockefeller Library. “I loved the Rock,” Weiss says, “and also the old Pembroke Library—now extinct—where my mother [Dorothy Poole Charlton ’33] worked in circulation as a student.” Her own daughter, Margot Weiss ’90, would one day be a fan of the John Carter Brown Library. To put it slightly differently: Brown, and libraries, were all but destined to become a consequential piece of Ann Weiss’s history.

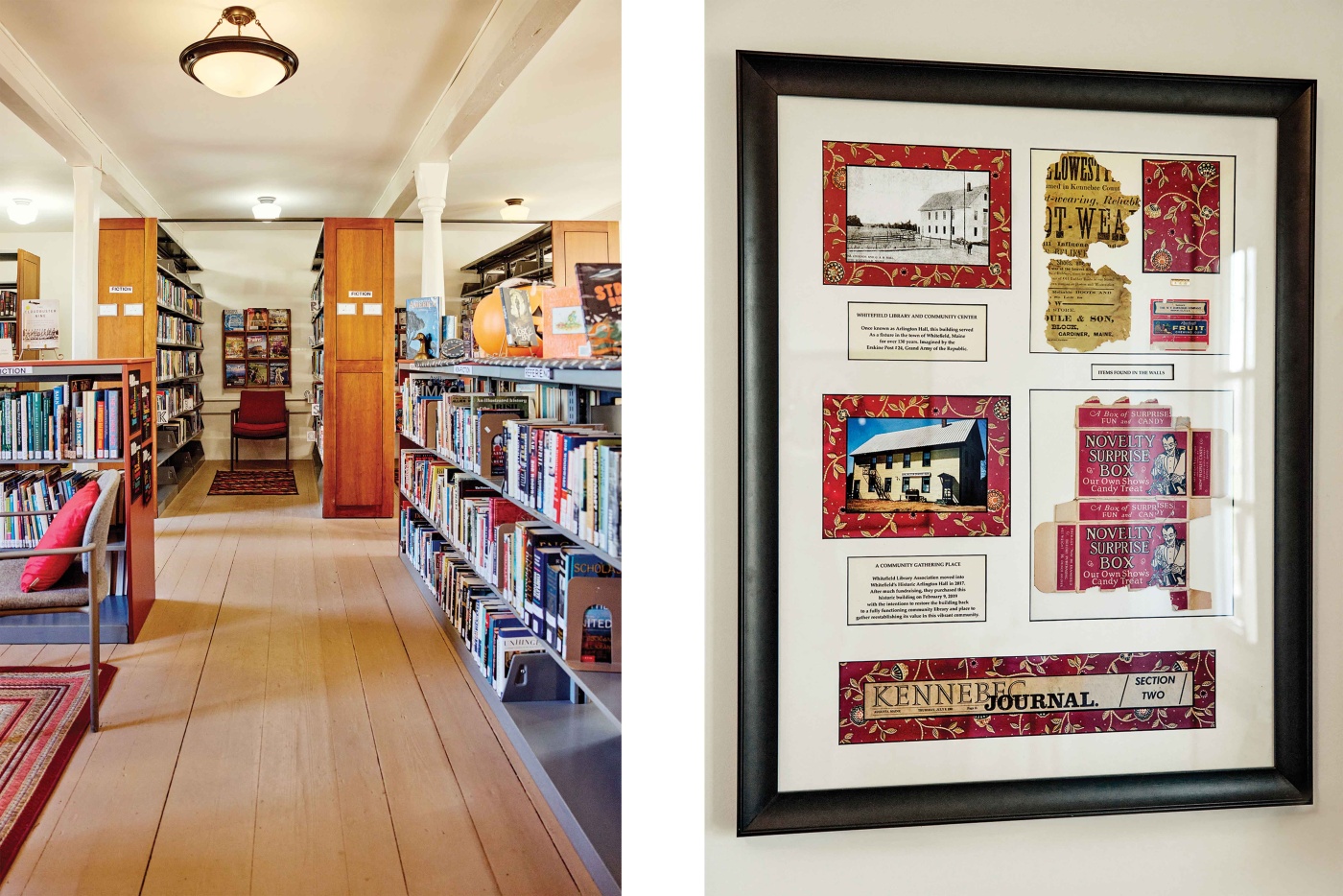

The Rock was designed to house a million and a half volumes. The Whitefield Library in Whitefield, Maine (pop. 2,408), where Weiss lives now, holds between eight and nine thousand. “We’ve got the Brontes,” Weiss explains. “Some classics. It’s very spotty. We’ve got an awful lot of Dan Brown. The complete Sue Grafton.” Does it sound quaint? Perhaps it is. But it’s something else, too. The creation of this small-but-mighty rural library has had an outsize impact on the town—and on Weiss herself. “I can only say,” she says, “that this has been one of the greatest experiences of my life.”

As Weiss tells it, it all started with a second-grader’s complaint in 2017—“Check the date, though. COVID has messed up my sense of time.” Okay, it was 2016. Young bibliophile Quinn Conroy wrote the select people in town to say he thought there should be a library in town. Specifically, he wanted a library open when the school library was closed, because “‘in the summer it’s kind of boring here’—I think that’s a quote,” Weiss explains. Somebody wrote a letter about it to the local paper and a movement was begun.

The first plan, to keep the school library open year-round, hit one snag and then another: the first summer the school was abating asbestos; the next they were repaving the parking lot. “It became clear that the summer was always going to be like that,” Weiss says. And then a stroke of luck: someone offered up the Grange Hall, with the caveat only that they’d need the tables for their suppers and some space upstairs for their rituals. There was no heat or insulation, so they wouldn’t be able to stay open in the winter, but local folks donated books and furnishings, and a warm-weather library was born. “We were open three summers that way,” Weiss explains. And then it was March of 2020, they were gearing up for their annual April opening, and, well, you can guess what didn’t come next.

Library-wise, at least, “COVID was a blessing in disguise,” Ann says. The Grange was dissolving and the ownership of the building—officially known as Arlington Hall on Grand Army of the Republic Hill—reverted to the state. The library group secured a grant from a local bank and bought it. “It was in pretty rough shape,” Weiss says. “The clapboard needed replacing. The windows rattled in the breeze. These four retired people—they call themselves the Geezer Gang—did most of the work.”

“We claim that we have 300 years of life experience,” says one member of the gang, namely—and prepare for the plot to thicken in a totally Brown kind of way—Erik Ekholm ’68. “Although I’ve known Erik for years,” Weiss says, “I didn’t realize until we began the library project that he was just two years behind me at Brown!”

“We were using Ann’s barn to store the library shelving,” Ekholm says, about the bookshelves he’d gotten from the Jackson Laboratory in Bar Harbor, “and we got to chatting—found out we’d both gone to Brown.”

“I’m definitely on the brick and mortar side of things,” Ekholm explains, which makes sense, given his background. After majoring in anthropology and specializing in archaeology at Brown, he’d gone on to work at the Plymouth Plantation, where one of his Brown professors was the museum director. As director of exhibits, Ekholm created a program of reconstructed buildings with costumed staff. He’d done some graduate work but, as he puts it, “Over time, I got less and less into the academics and more and more into the timber frame building.” Eventually, Ekholm realized he could work anywhere, and he and his family moved to Maine—a place they’d spent many happy summers. Ekholm built houses locally and rebuilt historic structures at museums around the country. Now that he’s retired, he describes his job as “professional volunteer.” “I joined the local fire department. I became an EMT. Then a paramedic. I’m on the facilities committee, the roads committee, the building committee. The library was a natural.”

While Ekholm and his geezers set about renovating the space, Weiss was occupied with the getting and cataloguing of books—especially children’s books. This was a natural fit: Weiss’s career had involved both a long stint editing at Scholastic Magazine as well as writing and publishing 30 nonfiction books for children and young adults on topics ranging from the nuclear arms race and the Supreme Court to religion and public life. Unsurprisingly, she had also done work—paid and unpaid—in multiple libraries. That continues: Whitefield is an all-hands-on-deck kind of library, and in addition to expanding the catalog, Weiss explains, “I work at the circulation desk, like everybody else.”

“The work is ongoing,” Ekholm says, about the renovations—they’re turning to the parking lot next—but the library is growing. There’s a paid staff position now and a scanner to replace the library-card system they’d been using. There is children’s programming and insulation. There is heating and cooling. Donations have come from all over the state—from banks and regular people and also Stephen King. Plus, there is history preserved. “Without the library,” Margot says of the Grange Hall, “this lovely old building would have continued falling into ruin. The library has been created by volunteers out of nothing—with donated books, free labor, and love.”

“Try my landline,” Ekholm writes in an email. “It is the best connection in dry weather. When it rains, it develops too much static to use. There are many wonderful aspects of living in rural Maine; connectivity is not one of them!” Except, of course, for the real kind, the human kind, which they clearly have in abundance.