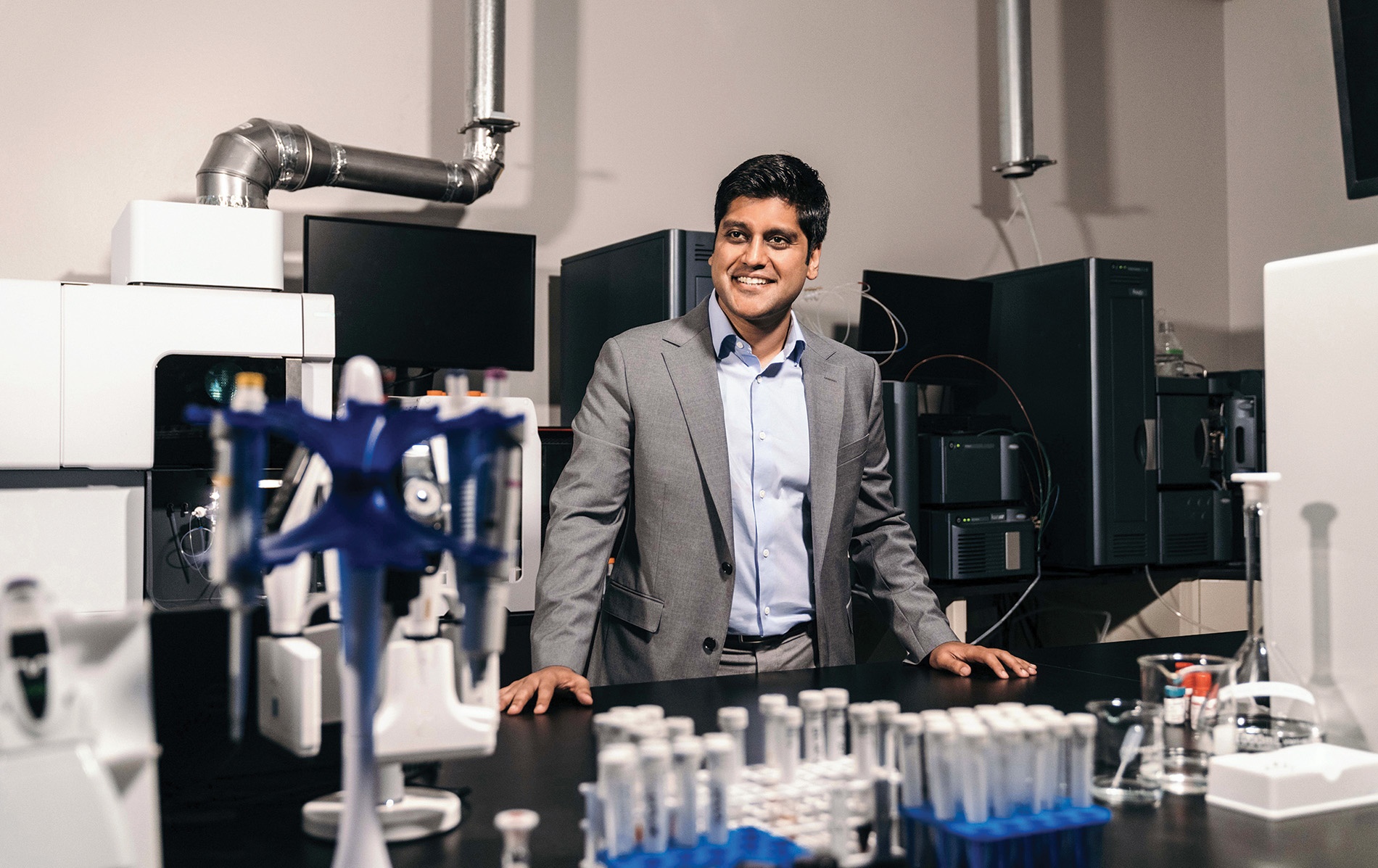

It started with a poker game. Gaurab Chakrabarti ’10 was playing cards with friends from University of Texas medical school in Dallas when he began talking about his work in cancer research. He was using enzymes to increase cells’ natural ability to create certain chemicals that might kill cancer cells, he told them, and recently discovered one that could naturally produce hydrogen peroxide. At the card table was Sean Hunt, a friend’s husband and chemical engineering student visiting from MIT. Coincidentally, Hunt was working to make hydrogen peroxide manufacturing more efficient.

“We kept chatting for hours,” Chakrabarti says. “We realized that perhaps we were both trying to solve the same problem.” From that chance conversation, they created a clean manufacturing start-up, Solugen, which uses unique combinations of protein enzymes and metal catalysts to efficiently create chemicals. The best part: instead of cracking dirty petrochemicals, the company uses all-natural ingredients such as corn syrup, making molecules with zero waste or emissions. After winning a competition at MIT to launch the company in 2016, the two started by supplying the float spa industry with hydrogen peroxide they created in a makeshift reactor in their lab. Now they boast two bioforges churning out a growing roster of chemicals.

“The only thing I ever wanted to do was figure out ways to solve cool problems,” Chakrabarti says of his upbringing in Dallas. Every summer, he and a cousin would challenge each other to an invention competition, starting with potato guns. Chakrabarti felt at home in the Open Curriculum: “It’s exactly what I wanted—where you’ve got an engineering person finding a solution from a person studying Russian literature.” He designed his own major in computational neuroscience, veered into cancer research at medical school, and then had his enzyme eureka moment.

Solugen now makes hexamethylenediamine —a component of nylon, previously one of the dirtiest chemicals to produce—and an organic version of PET plastic. He estimates the company, valued at $1.8 billion, could produce up to 90 percent of all industrial chemicals. “Every time we build a new plant, we’re creating a new carbon-negative approach to the chemical industry. So our bottom line becomes a social mission. Rarely in life can you say if I make money I’ll do good.”

Even as he looks to expand Solugen’s roster of chemicals, he hopes to focus more on education, empowering young people to become inventors. “I know the passion and love I have for this, and if other kids can see it, we can create much cooler stuff for society.”