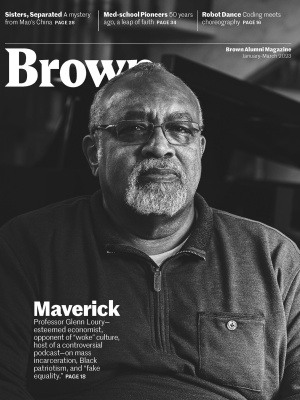

Divided Lives

At the dawn of Mao’s China, Professor Zhuqing Li’s aunts were separated by opposing ideologies.

Twenty-two-year-old Zhuqing Li dreamed of getting a graduate degree but thought she would never advance further than her posting as an English teacher at a provincial school in China—until the day she first met her mysterious Aunt Jun in the lobby of the White Swan hotel in Guangzhou.

No one in Li’s family had ever before mentioned the existence of Jun, her mother’s older half-sister. She’d been gone for 33 years when she returned home to China from the United States in 1982, trailed by a watchful Communist security agent.

Li did not yet know of all the things that could not be said between Jun and her relatives in the still politically charged climate of post-Mao China, but she could sense how her aunt’s life apart had shaped her—the elegance of her bourgeois step, the warmth of her extended handshake and the lightness of her smile, so different from the reserve of the rest of the family.

Later, learning of Li’s aspirations, Jun offered to sponsor her niece’s education in America, where Jun ran a Chinese restaurant—but only if she got herself accepted to a program. Soon Li was in grad school at the University of Washington.

It was only after many years, when Li was settled into American life as an accomplished professor of Chinese linguistics with a mortgage, a marriage, and two boys, that she started to wonder about the story behind her aunt’s unexpected appearance and life-changing generosity.

Jun embraced her niece’s questions about the past as conversation starters rather than blows to flinch away from, as the rest of Li’s family might’ve reacted. They started to talk, sitting together in the guest room of Jun’s Maryland home, under a portrait of General Chiang Kai-Shek, Jun beginning to tell a story that sent Li on a decades-long search for more details. The story became a book, Daughters of the Flower Fragrant Garden, published last June, that brings the birth of Communist China to life.

“I realized I knew nothing about the human experience, the human story of history,” says Li, a professor of East Asian studies at Brown, of China’s transition. “What [Jun] was telling me was the real history. And whatever I had read before in the books was just a skeletal structure of that history.”

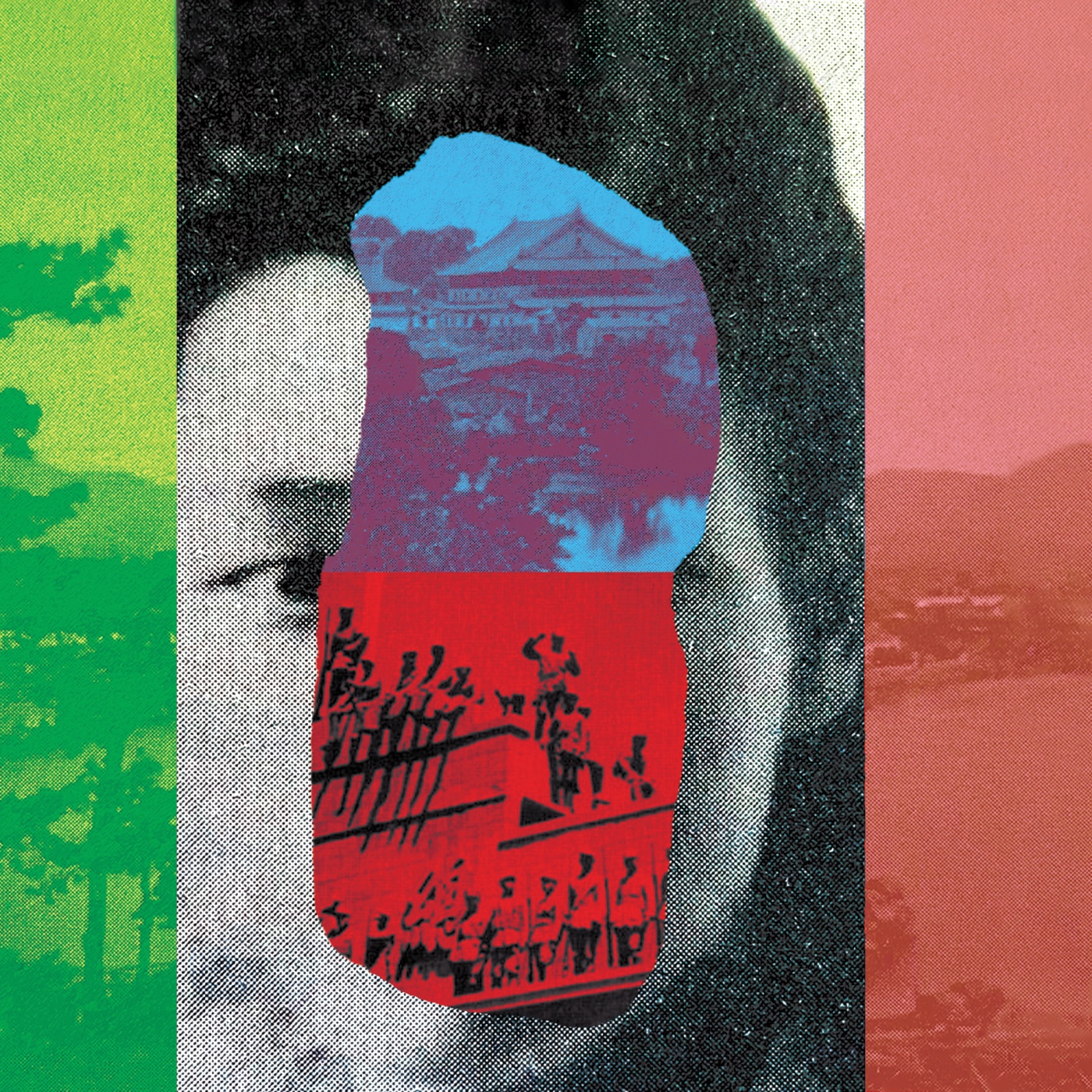

Daughters of the Flower Fragrant Garden recounts how a mistimed ferry ride led Jun to become part of the founding of Taiwan and later to immigrate to the United States, while her younger sister, Li’s Aunt Zhen, and the rest of the family endured the throes of Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution and the emergence of modern China—Zhen rising to prominence as a doctor in the Communist mainland, publicly repudiating her Nationalist sibling.

Li gathered the stories of Jun and Zhen often in late night phone calls to China, unwinding the fraught, existential choices that shaped the lives of her family, while working to transform herself, over the years, into the sort of writer who could traverse the brutal intricacy behind the creation of two countries and the separation of two sisters.

A garden, lost

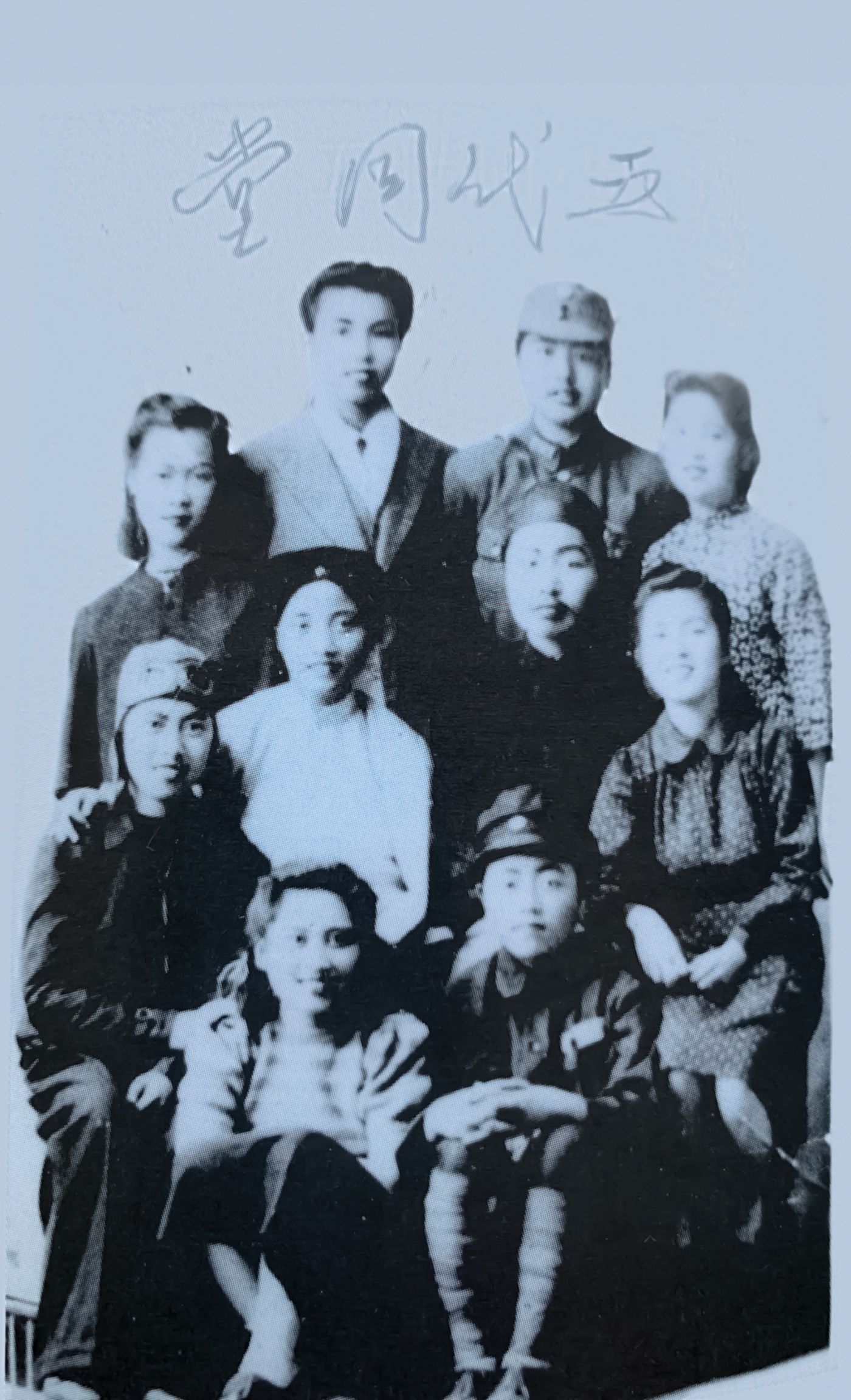

“To be separated of course means having been together once, and Jun and [Zhen] started out from the same place, a house named the Flower Fragrant Garden, a spacious, verdant family compound, one of Fuzhou’s biggest and richest homes,” Li writes.

Li herself remembered the mansion, having lived nearby as a child of China’s cultural revolution in the early 1960s, once peeking through a hole in the wall to glimpse the home’s great red lacquer door and lion-faced bronze knockers, but never knowing this had been the birthplace of her mother and two aunts until her conversations with Jun.

Li followed her aunt’s reminiscences through the gates into the courtyard where the prosperous family invited the whole town to its annual mooncake festival, past the three kitchens all put to use for New Year’s celebrations, into the residences of Li’s grandparents, re-entering Jun and Zhen’s briefly idyllic childhood.

Li’s mother and the rest of Li’s family had offered no such recollections. For them, memories of the lost mansion and what it represented—what the family had sacrificed to the dream of the new China—were too painful, Li says.

The walls of the Flower Fragrant Garden could not keep out the violence of the civil war between Mao Zedong’s forces and Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist army, leading to the formation of Mao’s Communist People’s Republic of China in 1949 and exile of the nationalists to the island of Taiwan.

At the time, Jun had just taken a ferry to vacation on the island of Kinmen, which promptly became a frontline for the retreating Nationalists in the defense of Taiwan. Marooned three kilometers from the mainland, Jun could not return home.

“All of her recent dreams, all of her life’s goals had suddenly been reduced to nothing,” Li writes.

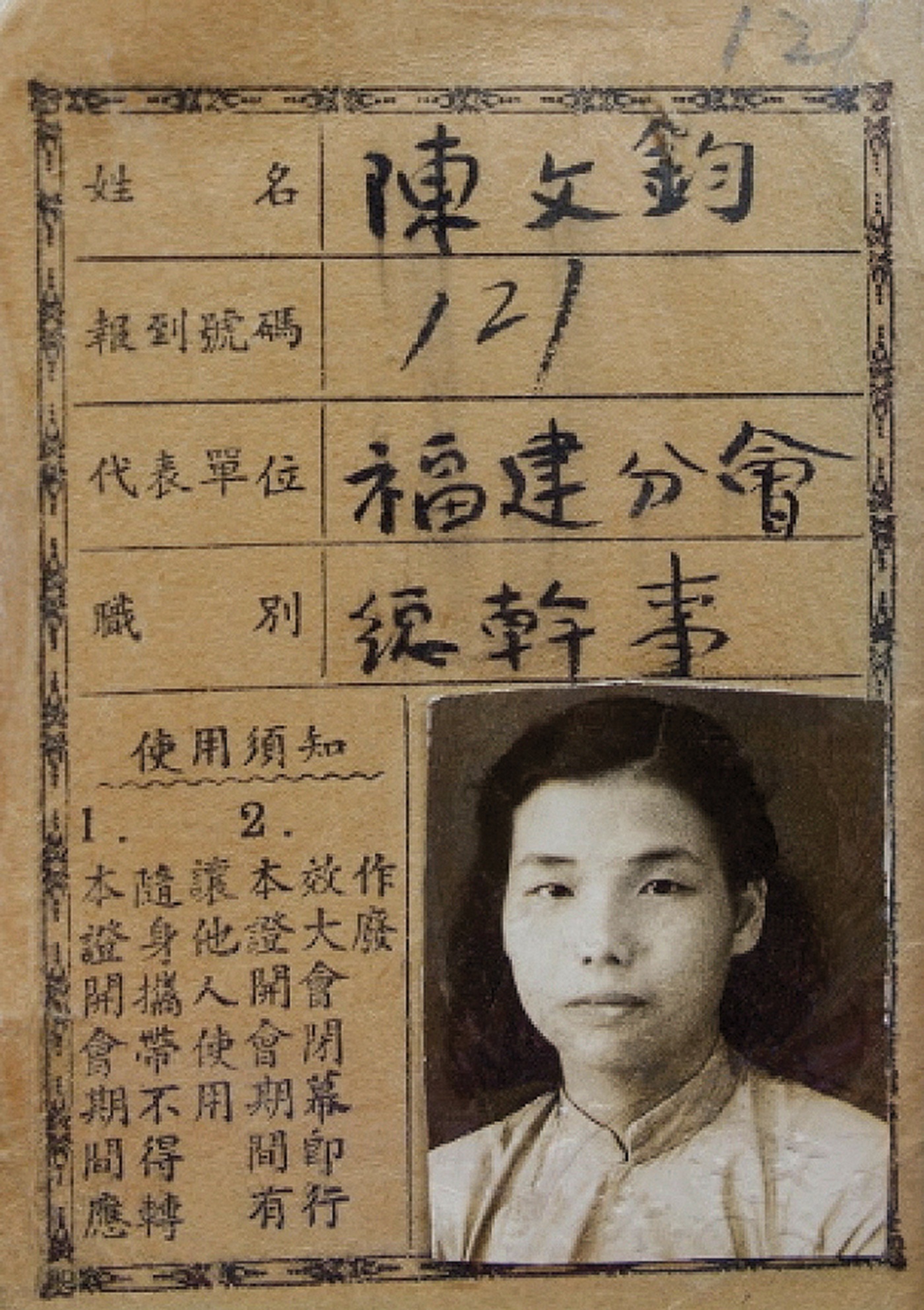

With limited options, Jun eventually became a pro-Nationalist journalist on Kinmen, attained the rank of major in the Nationalist Army, married a general, and later forged a successful street-sweeping business in Taiwan.

Yet her prominent connection to the Nationalist cause jeopardized her sister Zhen and the rest of her family on the mainland as purges mounted to eliminate traitors of Mao’s cultural revolution.

“I often put myself in that position, what am I supposed to do?” says Li, of Jun’s situation. “Do I sacrifice my entire life and career, my entire future? Just so that my family could survive? I don’t have an answer.”

Terror and subversion

If Jun was expansive and whimsical in retelling her past, Zhen countered her niece’s questions with unsentimental explanations, wrapped in the political armor of her Communist ideology.

“She still talked like a revolutionary,” Li says. “And she hadn’t changed.”

A pioneering, authoritative physician dedicated to improving healthcare for rural women, Zhen had no time for conversations with Li and instead gave her a copy of a memoir she’d written, which she said contained everything she wished to share. Focused on Zhen’s medical accomplishments, the book did not even mention the names of her husband and children.

When illness confined Zhen to bed, forcing her to pause her work in her 80s, Li finally had an opening. Huddled in her cold New England attic past midnight, Li drew out her aunt’s story through a year of phone calls as Zhen hoarsely sketched out life within the treacherous political landscapes of Mao’s China.

“When she approached political issues, she buried them in a totally different context,” Li says.

Early in the revolution, Communist operatives confronted Zhen about her connections to her sister, who was, Li writes, “behind enemy lines.” Zhen chose to burn all her sister’s letters, including her address, to save the rest of the family. Cut off by her sister, Jun had no contact with her family for decades.

It was far from the last time the family was forced to make such decisions, later trading one of Zhen’s baby brothers for a sack of rice during the mass starvation of Mao’s Great Leap Forward.

“I refuse to judge them, because I did not have to go through what they had to go through,” Li says. “I was shielded from that kind of political terror.”

Unwilling to discuss the most painful moments of her past, Zhen nevertheless wrote out, with trembling hand, a list of names for her niece, who had come to visit her on her deathbed. Gathering testimony from this list of her aunt’s childhood friends, colleagues, and acquaintances, Li could begin to relate to the impenetrable Zhen, who had been so committed to the ideals of the Communist revolution that she had named her third child Jiyue, or “Continue the Leap,” in 1958 though at the time many rural dinner bowls contained only rice water. An estimated 20 million people would die in the coming years.

Li learned, indirectly, how Zhen’s education and ties to Jun haunted her until the day Mao’s zealous Red Guard youths ripped up her medical license and forced the renowned physician to stand for weeks outside the hospital she once ran, her head shaved in shame and a sign draped from her neck, proclaiming Zhen a “counter-revolutionary quack doctor.”

Zhen’s ideals for a new China were “upended by political fanaticism and incompetence,” Li writes. “Doctors who could have saved lives spat on at the hospital entrance and consigned to clean toilets, patients they could have saved reduced, literally, to ashes, their children taught to hate and guard against a nonexistent enemy, rather than to seek useful knowledge.”

Exiled to countryside re-education, Zhen spent three years digging up yams from frost-covered earth or bending over, ankle-deep in the mud, to farm rice. Li writes that Zhen spent her 43rd birthday far from her children and the wreckage of her medical career, alone in a rural mountain village where “her new dreams, which had been born with the new People’s Republic…seemed to shrivel in this cold, dark, silent night.”

“I refuse to judge them, because I did not have to go through what they had to go through. I was shielded from that kind of political terror.”

But Zhen found her way back into medicine and political good when her record was cleared five years later after arduous self-criticism sessions. She eventually resumed her medical campaign against the fistula and uterine prolapse—post-childbirth ailments, in fistula’s case often causing an ostracizing stink—which she had begun years before when she opened a clinic in Li’s grandmother’s hometown of Nan’an, in southeastern Fujian province.

Even as Zhen shrouded reflections on her life in the language of revolutionary self-criticism, Li believed she saw shimmers of subversiveness. Later conscripted to run a provincial program sterilizing women during the early years of China’s One Child Policy, Zhen appeared to sabotage the initiative, including when authorities brought one woman directly to Zhen in the middle of the night and demanded an on-the-spot tube-tying sterilization, which Zhen performed. Miraculously, the woman still gave birth the following year. Zhen chastised herself in her memoir: “The stubborn egg fulfilled the parents’ dreams and yet added one more failure to my long career.”

“She basically made it sound almost routine, and not political,” Li says. “She had that talent.”

Transformed by history

Though she connected more readily with the amicable Jun, Li understood Zhen’s world because she herself had lived within it, sent to her grandmother’s home in Nan’an as an emaciated five-year-old while her college-educated parents suffered re-education elsewhere. She knew the folds of mountainous terrain, the ache of balancing water jugs on bamboo poles, and the injustice of the traditional gender norms that saw her picking cow droppings for fertilizer rather than studying in a classroom, only rescued from this fate one year later when her mother returned.

“I could certainly imagine that, had I been a little older, I would have been married off and lived that kind of life and suffered that kind of illness, becoming one of Zhen’s patients,” Li recalls. “It was not at all a stretch.”

But just as her aunts never stopped evolving, Li reinvented herself to meet the new demands of life as China’s revolutionary ardor subsided with the death of Mao in her teenage years and pathways for education re-opened.

Zhen, in her early 70s, past the age most doctors retired, trained in the newly arrived medical procedure of in vitro fertilization and then devoted the rest of her life to bringing children to the families of Fujian province. She continued working into her 90s and passed away soon after the publication of Li’s book, which had given her the pseudonym Hong.

Jun, who died in 2014, had given up her prosperous business and social life in Taiwan to immigrate to the U.S. because she saw it would be the only pathway allowing her to eventually reunite with her lost family in mainland China, closed off to Taiwanese citizens until the early 1980s.

“These two women, through crazy matters of fate, were equally determined to build their own self identity,” Li says. “When life, time and time again, put them back to the bottom, they stood up to emerge triumphant in their separate worlds.”

The same could be said of Li herself. Only later realizing how Jun’s gift of an American education was her way of reclaiming the abdicated responsibility of an eldest daughter after all those years of absence, Li struggled for years to navigate classes and learn anew an entire culture: what clothes to wear, what newspapers to read, how to ask a question in class or approach a professor.

In her middle age, holding the strands of her aunts’ stories in an

ever-growing pile of notebooks, Li embarked on a years-long path of literary self-education, scouring the classics, producing draft upon draft of her manuscript in the hours between teaching and parenting, cold emailing established writers for advice and even chasing down, barefoot in the snow, a passing English teacher neighbor with a request to read a chapter.

“Writing the book I really used every single minute I could squeeze from my life without sacrificing my time with my children or family,” Li says.

She believes the story reflects not simply a family history but the muddle of Taiwan and China itself, her aunts’ choices and circumstances embodying a nuance she fears most politicians, media, and even Chinese and Taiwanese people do not see.

“People from the mainland are usually dismissive of Taiwan and vice versa,” she says. “And I think there’s an unease, if not animosity, between these groups of people. Through the human experience [of Li’s aunts], I think both can understand each other a lot more.”

Jack Brook ’19 is a freelance journalist in Phnom Penh. His writing has been published in the Christian Science Monitor, Jerusalem Post, Miami Herald, Southeast Asia Globe and other outlets.